by Alec Ash: According to animist beliefs, nature is alive with spirits…

That’s a problem when a mining boom is despoiling the landscape. The solution, as Alec Ash discovered in Mongolia, is to employ a shaman to intercede with the supernatural.

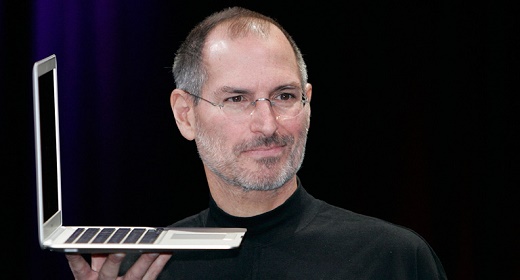

he rites began at dawn, as they do every year on the first morning of the Mongolian spring. By noon, hundreds of faithful were gathered around the master shaman Byambadorj as he channelled the spirit of the tree into his body. To invoke the other world he twanged a mouth harp with his fingers, while an assistant held a microphone to his lips to capture the eerie sound. The onlookers held their palms up and cried “Hree! Hree!” – come! come! – as Byambadorj banged on a large sheepskin drum which he held over his face, dancing as he went into his trance. The crowd pressed in, holding up their camera phones, to hear from the spirit world.

The spirit spoke in a throaty voice, but its first utterance fell short of the supernatural. The audience, it said, should stop taking photos. Then it cackled like a comic-book villain, downed a shallow bowl of vodka and smoked a cigarette through a long, thin pipe, surveying its acolytes.

The spring rites took place in a dusty copse in the far north of Mongolia, near the Siberian border. Byambadorj’s trance was the main event, but the scores of other shamans telling fortunes and dancing around fires created the atmosphere of a country fair. Some spectators had driven eight hours from the capital, Ulaanbaatar. In the field used for parking, hawkers sold hot milk and breakfast out of the boots of their vans and nomads peddled trinkets and wolfskin coats ($126 a fur, hunted and skinned themselves). One ger, the domed fur tent used by Mongolians for millennia, doubled as a cafeteria.

In the middle of a clearing, surrounded by a low wall made of stacked teacakes, was the mother tree, Eej Mod – tall, white and leafless. Ceremonial scarves were strung from a point midway up the trunk to form a wigwam at the tree’s base. Worshippers circled inside, praying, muttering, and tossing milk and vodka at it. Sweets and banknotes were stuffed into the bark, and a stone slab overflowed with hard cheese and other dairy-based offerings. A low building nearby had been constructed around the root of a previous mother tree (evidently a fickle notion) which, according to a sign, had perished in a forest fire started by a policeman’s cigarette years ago. But the new mother was no better off. There is only so much vodka that a tree can take. It was dead.

The head of Mongolia’s Corporate Union of Shamans was in a ger off to the side of the ceremonies. It is the union’s job to regulate shamans and certify their credentials – a taxing undertaking, as the number of shamans is increasing apace and anyone can become one if they claim that a spirit visits them. The union official, Jargalsaikhan, was looking unhappy. Byambadorj is the big attraction, but the union disapproves on the grounds that he is an arrogant show-stealer – but also for other reasons, including that he ignores their regulations by wearing his glasses while receiving the spirits. The union’s website (mongolianshaman.com) shows pictures of the mother tree in 2012, healthy and green, and in 2016, white and dead, along with passive-aggressive text implying that Byambadorj’s illegitimate practice killed it.

Byambadorj, who is a celebrity in Mongolian shamanism, seems untroubled by the union’s hostility. Eej Mod is his show. Once the spirit was in him, he had the rapt attention of the spectators. In the summer there will be a deluge, the spirit predicted: beware of floods. Everyone should think on their dreams and wishes. And that was it. Byambadorj banged his drum again to exit the trance, and as the spirit left his body he blinked and jerked his head, as if returning to consciousness. The crowd immediately mobbed him in a formless queue to receive his blessing. Byambadorj took the mic and told them to stop shoving.

When it was over, Byambadorj collapsed in his fold-out chair to drink milk tea with a vodka chaser. All that was left was to watch the fires slowly burn out, the shamans and believers to wander back to their cars, and the spirits to retreat to their higher plane, leaving humans to more material concerns.

Rites of spring

Milk is flung on the tree to propitiate the spirit

Master of ceremonies

Blue khatas (ceremonial scarves) are hung on the mother tree, and shaman Byambadorj blesses his followers

Mongolians believe their endless sky is home to a spirit called Tenger, and every hill, lake and pile of stones on the steppe has its own spirit too. Mongolian shamanism – similar to native American animism – is the country’s native belief system and one of the most ancient expressions of spiritualism.

Banned during the 70 years of socialist rule in Mongolia, shamanism is now booming – as other religions are in other post-communist societies. You cannot throw a rock in Ulaanbaatar without hitting a shaman, who will probably tell you the rock has a spirit in it. In 1990, according to the Corporate Union of Shamans, there were ten shamans in all of Mongolia. Now they estimate over 20,000, out of a total population of a little over 3m. There are shamanic magazines, books, even a reality-TV show that aired earlier this year, the “All Mongolian Shaman Competition”, pitting holy man against holy man in challenges such as deciding which of 13 closed boxes has a personal object inside it. (In the episode I watched, none of the contestants guessed right.)

Out in the countryside, where there is nothing but steppe and sky, it is perhaps no surprise that shamanism has survived shifting politics and is still followed today. This is a harsh land, where good or bad weather can make or break a herder, and the gods of nature are cruel. But Mongolians are moving to the cities – half the population, 1.4m, lives in Ulaanbaatar – and yet the religious revival is still going strong. Two-thirds of Mongolians identify as Buddhist and 90% have some shamanic belief (the two are not mutually exclusive). There is also a handful of Christians.

Shamanism’s survival is not just the result of enduring superstition. Two developments in Mongolia have contributed to its recent growth. One is mining. During the early 2010s, Mongolia experienced a sudden mining boom. Its economy grew 20% a year, the fastest rate in the world at the time. That expanded the market for shamans, who intercede with the spirits on the behalf of miners, in a form of spiritual insurance against the damage that mines inflict on the natural world.

Shamans, believing that nature is alive with spirits, tend to profess an environmentalist creed. “The human race is out of touch with the natural world,” says Byambadorj. “Defacing and polluting nature is a great offense to Mother Earth. Shamans will unite to save this green planet if they live like nomads and follow the example of Genghis Khan.” But the apparent conflict between mining and animism does not trouble him. Quite the reverse. With the injection of funds that miners and other rich clients bring, shamanism has become big business.

What possessed them?

Byambadorj bangs his drum as he enters a trance

In their bones

Lamb ribs and fat are offered up on the fire

The second factor is nationalism, which can take extreme forms in Mongolia. As the mining boom took off, neo-Nazi groups began to emerge. Some of these groups, notably one called Tsagaan Khass, openly wear SS uniforms with swastikas, have talked admiringly of how Hitler made Germany great again, and have shaved the heads of Mongolian women who slept with foreigners. Others now primarily express their nationalism through environmentalism. Standing Blue Mongol, which used to be a neo-Nazi group but now engages in environmental activism, has co-operated with a collective of shamans in a campaign to save a mountain from a Canadian mining company, “to protect our national identity”. While Buddhism is an import from China, shamanism is an expression of Mongolian national identity.

Not everyone is a believer. In Ulaanbaatar I met a self-described activist and comedian – baseball cap, sports car with rap blaring, achingly urban – called Amartuvschin Dorj, who with his young peers dismisses shamanism as a “scam”. Apprentice shamans have to pay their masters a minimum of 2m tugrik ($840) in order to be trained, he said (other shamans I spoke to confirmed this, but some said it was a million, equivalent to the value of a cow, the traditional payment of old). This, and the gullibility of those who go to shamans for help, says Dorj, is just a symptom of a larger problem: “poor education.”

But although education is improving in Mongolia, the demand seems insuppressible. Our translator had visited shamans; our taxi driver’s daughter had recently become a shaman; Dorj’s own father was stripped naked and beaten with a metal-tipped wooden rod by a shaman. (When it didn’t help, he asked for his money back.) And the most famous shaman in all of Mongolia is Byambadorj.

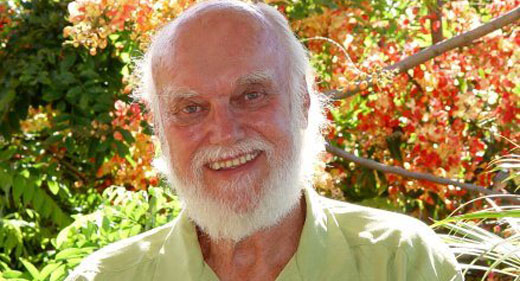

A stout man in his early 70s, with grey hair pulled back in a thinning ponytail, Byambadorj holds court at a walk-in centre in eastern Ulaanbaatar, next to a fried-dumpling restaurant. Inside, on a raised terrace, there is a fur tent where he sees clients, next to a man-sized tripod of wood covered in ceremonial scarves that channels the spirits on to a mortal plane. From there, steps lead up to a reception hall (complete with receptionist doing her nails) and office. Behind it all is a view of a stalled construction site, high cranes immobile in the sunshine, a common sight in the capital after the economy tanked when the price of coal fell.

Byambadorj was born into a family of herders in southern Khovd province in 1946. The first sign of his gift, he said, was a yellow snake that came into the ger when he was born. He began receiving spirits as an adolescent, with the guidance of his uncle, and while shamanism was forbidden he performed rituals in secret, despite the risk of imprisonment. In the 1990s he began teaching openly, as a zaarin or “high shaman”. In 1999 his uncle doubted his nephew’s gift, Byambadorj told me, and took him to a “PhD doctor of shamanism” – who confirmed not only that Byambadorj was a bona fide shaman, but also that he was “master shaman of the world”. (There is a copy of this doctor’s note in the back of his autobiography, alongside testimonials from his students.)

The ger where Byambadorj holds court is rich with nationalistic symbols. Behind his fur-lined throne is a large relief of two fierce wolves. On the wall is a portrait of Genghis Khan, who worshipped Tenger and whose spirit is central to shamanism. Like many other Mongolians, Byambadorj claims a direct bloodline to Genghis Khan. In the middle of the tent is a tassled helmet perched on a pole, black yak hair flowing down from it – the tug or sulde, an ancient Mongolian war banner – which he sits behind like the Great Khan himself.

Soul practitioners

Apprentice shamans prepare for their initiation

The shaman will see you now

The waiting room at Byambadorj’s office, and a woman consulting Byambadorj

When I visited Byambadorj on his return from the ceremony at Eej Mod, he was receiving clients. One was a woman with a badly inflamed finger; another was a student who wanted a blessing before he applied for a New Zealand visa. Sellotaped to a window was a menu of services. Ranging in price from 20,000 tukgrik ($8.50) for a first consultation to 300,000 tukgrik for the more daunting “Fire Worship”, the list also includes “Horse Head Violin Ritual”, involving a traditional Mongolian instrument, and “Byambadorj’s Vodka Curing”.

Byambadorj is tight-lipped about his higher-end clients, although a picture of him shaking the hand of the former prime minister of Mongolia hangs in his office. For most shamans, the richest pickings are in the mining business. At the Centre for Shaman Eternal Heavenly Sophistication, a man wearing an expensive-looking leather jacket, his wife carrying a Louis Vuitton handbag, was waiting to see a shaman to ask permission from the spirits to open a gold mine. He always consults shamans before making major business decisions.

Students are another major source of revenue. During the week I was with Byambadorj, four students were visiting – two from Inner Mongolia, which has been a naturalised province of China since the 17th century, and two from the Russian Republic of Kalmykia, west of the Caspian Sea. The Corporate Union of Shamans stipulates that shamans should have no more than 13 wards. Byambadorj has lost track, but estimates he has over 100. He once had a ward called George, who lived in London, and whom he describes as “a soldier of Genghis Khan”.

At the end of the morning’s consultations in his ger, Byambadorj initiated the two Russian students into the shamanic ranks. They had been studying with him for a year and a half, and now they had finished their course. Byambadorj received them in turn from his throne, handing each a lapel badge and a booklet testifying to their qualifications, to enable them to take clients of their own. As they knelt to receive their credentials, each passed him a bottle of vodka, which Byambadorj added to the collection on the table in front of him. Held lower, more modestly, they also handed over a wad of cash.