by Hara Estroff Marano: Grief has always been a difficult emotion in America, and the COVID crisis throws into bold relief what happens when grief has—quite literally—nowhere to go…

The evidence suggests that most people summon strength and powers of reflection that far surpass their own expectations.

It was five o’clock on a lazy Sunday afternoon two weeks into pandemic lockdown in Oakland, California, and Keeley Mooneyhan was binge-watching movies in the family room with her daughter, newly COVID-furloughed from college. Mooneyhan herself was semi-quarantined, having recently returned from a trip to Africa. Suddenly, her husband appeared in the doorway, looking lost in his own home. Even the words he issued seemed to come from a distant place: “My sister’s gone,” he said. “She’s dead. We don’t know what happened. That’s all I know.”

Raw and shocking, the news drew the three into a long, emotional embrace that dissolved only when Mooneyhan moved to lay some groundwork for grieving. There were just so many layers of loss; the woman who died so suddenly was not only her husband’s sister and her daughter’s aunt but also her own best friend from college, the one who had introduced her to her husband in the first place. Every one of those now-ruptured links was exposing the normally unimaginable fragility of life.

Mooneyhan, who runs a boutique mergers and acquisitions consultancy, first had to face the challenge of getting to the funeral, across the country in South Carolina. It took days to reach the difficult decision that gathering with extended family could be more curse than consolation, possibly compounding the loss, certainly adding to upset by potentially exposing all to the novel coronavirus during travel and transfers. Even if Mooneyhan’s family took the risk, there was no guarantee that they could get back home; California was set to impose restrictions on movement. A service in South Carolina was planned to be conveyed by camera from the funeral home, but it was not interactive. Mourners could observe the event from afar, but not share memories or musings.

Unable to assemble with others pained by the loss, struggling to understand the sudden death, feeling the acute awkwardness of asking disquieting questions from afar, Mooneyhan and her family settled into an uncomfortable state of estrangement from events. All the anomalousness shrouded the death in disbelief. “What you’re trying to do is get some human understanding here,” says Mooneyhan. “Having so many unanswered questions and the filter of distance make the death feel like a bad dream. It could just be that we’re in a prolonged nightmare together.” She is certain that the death will become more real when they eventually gather with her husband’s family. “Then we can have the kinds of conversations that allow you to heal together.”

Grief has always been a difficult emotion in America, disenfranchised in a culture fixated on happiness and positivity. But the COVID crisis has thrown into bold relief what happens when grief has literally nowhere to go, when for any reason at all it is deprived of expression—especially now, when the public good discourages even small gatherings and condemns companionship, that most human of antidotes to raw absence.

The pandemic has also forced into the open the awareness that there are a multitude of losses that garner no memorial placard yet beg for acknowledgment and attention—from the extraordinarily abstract loss of certainty and security to the more concrete loss of a business or a job, without which so many also lose that most ethereal but essential of things, their identity. Then, too, there are feelings of sadness or slowness that are not even recognized as grief, because disruptions of life can disorient anyone, and there is nothing specific to pin that mood on. Nor are there rituals or routines through which to channel grief for such losses. And so, for many, grief itself goes underground, where the pain of loss cannot be ameliorated or probed for meaning, as it must, and, too often, lurks in the shadows as a sense of alienation.

Pathways of Predictability

Any loss presents a big challenge, affirms psychiatrist Wendy Dean. The compound losses occurring now add to that. “We don’t do a good job tolerating loss or discomfort of any kind,” observes Dean, who runs the organization Moral Injury in Healthcare. “We tend to look away from it. It’s hard to sit with it and process it. Our everyday rushing leaves us no time to assess what we really want, and now we are all being asked to reassess our priorities and values. How do we relate to loved ones versus material possessions? What are the things we value most?”

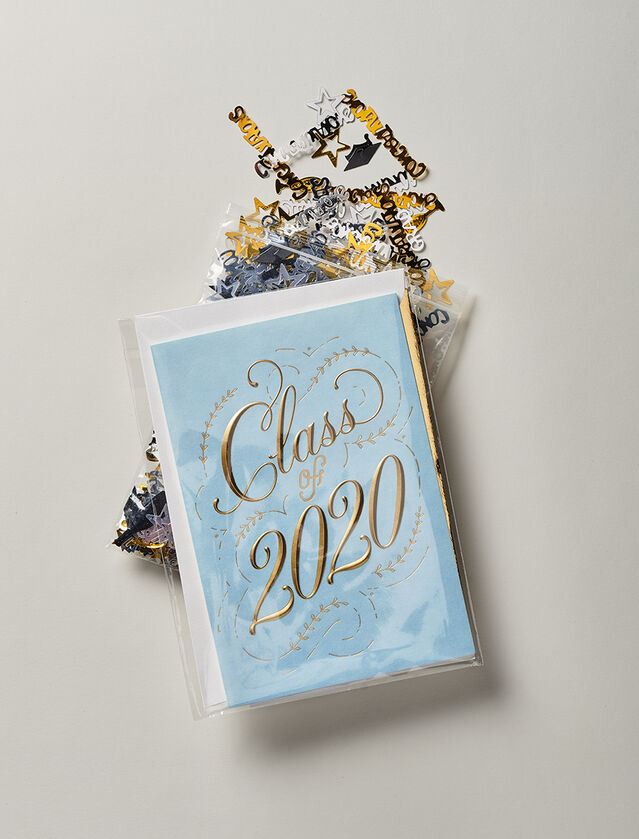

With two sons on the cusp of adulthood, Dean is particularly concerned about the many young people who have been deprived of the experience of graduation ceremonies this year. According to the National Center for Education Statistics, that’s approximately 1 million candidates for an associate’s degree, 2 million for a bachelor’s degree, and just over a million for an advanced degree. “You graduate to a job, to getting an apartment,” observes Dean. “These students are not just missing out on a ceremony. They’re losing a predictable pathway to finding a future.” The loss of predictability may be one of the most unsettling experiences of all.

In addition to the collegians, there are the 3.7 million who were scheduled to graduate from high school this year. Max K. is one of them. He was happy at the prospect of leaving home in Michigan for college. But before he found out that he was accepted at every place he applied, graduation disinvited him. No ceremony. No celebration. No pranks. And of course, no prom. He felt sad, he says, about not having a formal graduation—but then he stops, and after a long moment, he adds that he feels guilty for saying so because so many people have died from coronavirus infection.

There’s plenty of reason to feel personal privation over the absence of graduation ceremonies. After all, they’re an emblem of achievement, an opportunity for accolades, an occasion for pride. Life needs such events under all circumstances. Also they’re a milestone of maturity, and taking the time to acknowledge them as such works as a kind of push-off to the challenges ahead. The future feels less certain, more rocky, without the landmarks.

Of course, Max knows that his life will go forward, that he has a future, if with a little less clarity for a while, because he did what loss forces us all to do. It compels us to reflect on what is meaningful so that we can emerge with a perspective on life that more closely fits the new realities created by the loss.

Name the Pain

For the first time in the lifetimes of so many, the entire world is in communal grief. “We all lost what we thought our life would be on a day-to-day basis,” says New York psychologist Susan Birne-Stone. “There’s so much devastation right now that you just have to take a moment to acknowledge your own pain: I’m allowed to feel what I feel. Then it’s necessary to understand what’s lost and to name it.” Yet, like other psychotherapists around the country, she finds that clients are experiencing such a pile-up of losses that it is hard for them to identify and articulate all that is missing.

But once they do, they are able to know what’s required to make life feel whole again. Or to take any number of measures, from deep-breathing to writing, to self-regulate their feelings. What makes the abstract losses so challenging is that it’s difficult to know what action to take. But only then, says Birne-Stone, can anyone move on to thinking about what’s ahead. Of course, life can never be whole again the same way. “It might even be better,” she notes. “But at least you know what your life needs.”

When orders to shelter in place were enacted in urban areas, a client of hers became one of the many who were able to maintain their job and their income by working from home. Yet the man found himself increasingly unhappy. It took a couple of conversations to recognize that he was missing his daily commute. He lived alone, and his regular trips to and from work were important points of socialization.

It might mean nothing to someone else or even be an annoyance to others, says Birne-Stone, “but if a commute is your only social event of the day, it can be a significant loss.” It’s that identification, the understanding of exactly what is lost, that allows replacement in a fulfilling way—rather than with food, or drugs, or work. While loss is universal, grief is always individualized and idiosyncratic, even with the death of a loved one. There’s no formula determining which facet of an event or person is missed the most. Each life fits itself to experience in its own way.

Pain vs. Suffering

To deny the feelings of loss that suffuse so many lives right now, or to deny the validity of those feelings, she observes, risks turning pain into suffering. Pain is an unavoidable signal of distress that gives the lie to the mind-body divide: It’s an inextricable mixture of biological and psychological sensations in response to harm, and the perception of pain is influenced as much by cognitive and cultural factors as by purely neurological ones.

Suffering, on the other hand, is solely psychological, a product of the existential meaning we give to the experience of pain. As the Japanese writer Haruki Murakami succinctly puts it: “Pain is inevitable. Suffering is optional.” Unless acknowledged, says Birne-Stone, the pain of loss just festers within and, absent conscious awareness, subverts decision-making and every other element of functioning.

Grief gives us a job, says George Bonanno. It’s a command to slow down, to turn inward, and to recalibrate living in a world without—without our partner, without our friend, without our plans, whatever it is that’s gone. “You can feel grief for anything that is part of your identity,” says Bonanno, a professor of psychology at Columbia University Teachers College, where, as the head of the Loss, Trauma, and Emotion Lab, he studies how humans cope with loss and extreme life events.

Another distinguishing feature of the ongoing pandemic is that there is no way to know what will be permanently lost. New York psychotherapist Esther Perel sees an “invisible current of dread” running through lives right now. “We want to know: Will we ever be back to normal? When can I see my friends again? When will it be safe to open my business?”

That so much is in flux makes any loss even harder to bear, Bonanno says. “You have both the fear that your loss of livelihood is permanent and the anxiety from the continuing stress of the loss. There are so many ways people are just stuck.”

And yet, Bonanno is certain that the vast majority of people—probably 90 percent—will come to terms with what’s gone and resolve their loss, sooner rather than later. “We’ve documented how resilient most people are. Unfortunately, there is a percentage of people—around 10 percent—who don’t get over loss, at least for a couple of years.”

Waves, Not Stages

“Grief is undeniably difficult,” Bonanno writes in The Other Side of Sadness: What the New Science of Bereavement Tells Us About Life After Loss, but contrary to common belief, it is not always overwhelming. For sure, grief knocks us sideways, takes us out of the normal path of functioning for a while, but it rarely flattens us. For too long, he says, grief has been understood only through a clinical lens, narrowly focusing on the people who couldn’t get over a loss. That has become the norm for the grief response.

I am no stranger to loss. Some time ago, my husband died. We’d been close for 23 years. I remember one moment more than six months later when I wondered whether there would ever be a day when I didn’t cry multiple times. The pain was most acute each time I saw something or resumed an activity we had enjoyed together—going to the theater or the ballet or a concert, driving to our summer spot in Maine, seeing a whole roster of friends. Each resumption promised pleasures, but each was also a fresh reminder of what was missing.

The first time I traveled to a distant conference and retired to my hotel room for the night, I opened the door and just crumpled. There was no good-night message blinking from afar; I was blindsided by its absence. I felt completely untethered from the universe. But six days after the death, I had kept a longstanding lunch date with the publisher and publicist who were shepherding my next book into print. I told them not to mind, that I’d be fully present, but that there’d be moments when tears suddenly moved in like a squall in the rainforest, and just as quickly the sun would come out. For a long time, I told no one about this meeting or others I had in the weeks following the death. I was afraid of being thought uncaring. But when I recounted them to Bonanno, he smiled acceptingly.

Forget the idea that grief comes in more-or-less predictable stages that you move through over an extended period of time. Bonanno’s studies of the bereaved shift the paradigm. They show that “we have these profound emotional experiences that come in oscillations, or waves. In a book about his wife’s death, C.S. Lewis likened it to an airplane bombing—a big plane circles around, drops its load, takes quite a long time to come back, then bombs again.” Grief doesn’t take forever, Bonanno says: “The meat of the process occurs pretty quickly.” Turning to me, he adds, “You already went through something to get to the point that you could meet with your publisher in six days.”

The brain is a predictive organ, he explains. When we’re so deeply attached to someone that the attachment is part of our identity, our brain is geared toward predicting interactions with that person and relying on those interactions, even though most of the time we may not actually be in his or her presence. When somebody dies, or after the breakup of a significant relationship, our brain has the task of recalibrating the relationship.

The person is no longer physically in the world but is still in our head; we carry a mental representation of the person as part of our cognitive currency. “Your brain has to recalibrate what it means to never see the person again—without completely erasing the image within,” Bonanno says. “I just saw something that he would love. Or I want to tell her about what just happened.” The mind keeps rubbing up against the absence, and the reminder of the loss is sad and painful. The mental resetting is not an easy job, and in the first days after the loss occurs, it is hard to believe.

The sadness serves an important function. It takes the focus of our attention away from the world around us so that we can begin the mental reset. The sadness seems to slow the world down. And it sharpens our cognitive capability. A whole body of research demonstrates that sadness makes our appraisals of the world and of ourselves more accurate than usual.

Most of us have a desire to take away the pain of others, but some pain after loss is particularly useful, Bonanno points out, and many of the behaviors and rituals cultures have built around death are intended to augment the deep processes of adjustment. Funerals, for example, encourage a good cry in the presence of supportive friends. People come together to honor the dead person, which not only fosters acceptance of the death but also helps in the creation of an idealized internal image of the deceased, one in which the rough edges of everyday life have been smoothed over. Further, it connects everyone who knew the person and reaffirms social bonds in spite of the loss: He’s dead, or she’s dead, but you are still connected to us.

Adaptation

In his studies, Bonanno reports, people who are resilient cry when asked to talk about the loss early on, but they haven’t lost their ability to laugh. In fact, minutes later, the majority are able to laugh, and he knows that the laughter is genuine because his team video monitors the conversations and analyzes facial muscle movement to identify Duchenne, or real, smiling.

For all the research, don’t expect a handbook on resilience in the face of loss. “There’s no Do this or Do that and you’ll be resilient,” says Bonanno. Yet, he has identified a mindset that characterizes those who adapt to the loss without drowning in despair. They’re optimistic. They display a so-called challenge appraisal, which enables them to think, Okay, I didn’t want this to happen. It hurts like hell. But what do I need to do to get beyond it? They have a repertoire of self-regulatory strategies at their disposal that they deploy with a certain amount of flexibility. And elements of that flexibility show up as a distinct neural signature on brain scans.

But first, before everything else, they engage with the stressful event that occurred. It’s happened to me. What do I need to do? That involves optimism, challenge appraisal, confidence in coping. All are things that Bonanno and his colleagues can and do measure. And he uses the term “flexibility mindset” to sum up the process.

With sensitivity to context, those who adapt to the loss can call on a repertoire of strategies for managing distress. What do I need to do? What am I able to do? At one point it might mean leaning in to the emotional intensity of the loss, at another time and place it could mean distracting themselves. Each time, they are monitoring and evaluating the effectiveness and appropriateness of each strategy and adjusting their behavior to ease the emotional pain. Does this help me get through the day? Maybe it helps in the morning but not all day. Or I’m going to try talking to people more online. They are flexible in the self-regulatory strategies they muster and choose.

Brain imaging studies of people who are profoundly grieving show considerable activation of the corpus striatum, a major component of the reward circuit. “This is the desire part, I want this person,” says Bonanno. The activation occurs even when they’re not looking at images of the deceased or while they are doing a task that requires attention. They’re getting interfering thoughts; activation of the striatum is the brain marker.

Those who recover from grief also show that same brain signature of thinking about the person. However, they also show activity in the dorsolateral prefrontal cortex, the region of the brain that exerts executive control over memory and attention networks. It’s the region that brokers cognitive flexibility. But when researchers asked the bereaved study subjects about their experience, they reported that they weren’t thinking about the person. “It’s not that they don’t have thoughts about the person. The mind is going to go there a lot. But they’re able to put the thoughts aside. They’re able to shift attention away from those interfering thoughts,” explains Bonanno.

Acceptance of death turns out to be one of the predictors of successful outcome. People who are strongly dependent on the relationship for their identity have difficulty grieving the loss because too much is lost with the death. Bonanno points to the story I told him about my publishing meeting days after my husband’s death. “It indicates that you have other aspects of your identity so that you can still go on. It’s as if you’re saying, A piece of me is gone with this loss, but I’m still here because I’m still a writer who writes books.”

Bonanno finds himself in the curious position of trying to persuade people that they have mental resources that can get them through loss. “It’s a message that people are suspicious of,” he says. Mental health clinicians “may overestimate the prevalence of unresolved loss because they are around people who are hurting all the time.”

Psychologist Daniel Gilbert’s work on affective forecasting offers a reason why nonclinical people may be resistant to the idea of their own resilience. Bonanno, elaborating on Gilbert’s conclusions, explains, “When you feel pain, it’s hard to believe that you won’t always feel pain.” Moreover, he says, “One of the things that people hate when they’re grieving is for a person in their life to tell them that they’ll be OK. What do you mean, OK? I hurt like crazy. How can you tell me I’m going to be OK?”

But Bonanno tells them anyway. There’s definitely a period of adapting to loss, whatever the nature of the loss. “It’s all about getting engaged with the stressor,” he says. “When something happens to us, we need to think about it a little bit. That’s imperative. It’s an unusual situation. It’s dangerous. We need to actually talk to ourselves a little bit about it. What’s happening? What’s happening now? How do I deal with this? What do I do? We can answer those questions. We’re capable of it. I’m making the case that, hey, you’re not this basket case of grief. You’re resilient.”

As the pandemic grinds on and losses of all kinds mount, we can, and must, allow time for the anguish and sadness to course through us and to identify what is missing. We also have the opportunity to consider the bigger questions that get buried in the rush of everyday life: How can we move forward, honoring the losses we have sustained?