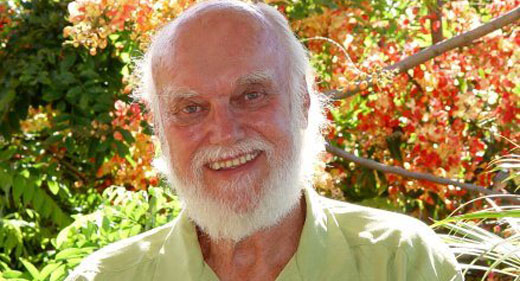

by Hara Estroff Marano: For many of the nation’s physicians, doctoring has become an almost unrecognizable activity, and it started long before the COVID-19 crisis. Unfortunately, the doctors have no idea how to take care of themselves…

On a long, cold weekend in January 2017, Wendy Dean found herself in the surreal position of listening to her husband, father of their two teenage sons, suggest whom she should remarry. That’s how fast he was sliding downhill. At his bedside at the local Pennsylvania hospital, Dean, herself a physician, was struggling to get the attending doctors to figure out why things had so swiftly changed, what had triggered the heart condition he was born with—and that had been managed so well that he too was an active physician—to go into free-fall.

Treatments weren’t working, and no one was taking the trouble to figure out why or come up with a Plan B. “They seemed not to realize my husband had been a highly productive clinician just weeks before,” says Dean. “They seemed to assume he had always been a cardiac cripple. They had no idea who he was and showed little curiosity about it.”

Camped beside him for a sleepless 48 hours, Dean could not bear watching the life drain out of the man she loved. She quickly arranged transport by air ambulance to a major medical center, but weather kept the plane grounded on a distant runway. Just the prospect of his transfer had led the care team to halt lab testing hours earlier. Desperate, Dean pulled out her phone and texted a colleague about the cardiac service at his hospital. Five minutes later, he called with the promise of a bed at the University of Pennsylvania, under the direct care of its chief cardiothoracic surgeon. By then, Dean had demanded that labs be drawn, and they now showed impending liver and kidney failure complicating heart failure.

No tears required. The episode ended well for the patient. He wound up with excellent care and recovered his old self. But Dean was never quite the same. The heart-wrenching saga exposed how much patient care is becoming a burden to physicians, and she apprehended that something was keeping them from doing what was etched into their DNA to do, what doctors sacrifice a whole decade to learn how to do. Months later, after she fully exhaled, she didn’t even fault the docs at the local hospital. She understood that they, like growing numbers of physicians in America, were caught so painfully between ministering to patients and meeting new administrative demands that often the only way they can carry on is to stop caring about what they are rigorously trained to do. For too many, that’s not even a possibility. They’d sooner kill themselves first.

And this was the case even before the coronavirus pandemic placed physicians at unprecedented risk and magnified the stress on them and on the medical system as well.

Death by Despair

Each year, 300 to 400 doctors in the U.S. take their own life, says the the American Federation for Suicide Prevention (AFSP). About one a day. That’s more than double the rising rate in the general population. Even then, the number is probably an undercount, because many physicians in distress may not—or cannot—renew their license to practice. Nor does it count the physicians who drive off a bridge so that their families can have the cold comfort of an insurance payout.

Imperfect as the data are, they show that among male physicians, the suicide rate is 1.41 times higher than the general male population. But among female physicians, the rate is 2.27 times that of the general female population. Physicians are successful at suicide, with a relatively high ratio of completions to attempts. After all, who better knows the vulnerabilities of the human body and has near-constant access to means?

Then there exist the many manifestations of distress that push doctors to the edge—overwork, emotional exhaustion, loss of a sense of personal efficacy, bankruptcy of compassion, indifference toward their work—adding up to burnout, now epidemic among U.S. physicians.

Surveys by the American Medical Association and others report burnout affecting up to 80 percent of physicians, depending on medical specialty, with an average of 50 percent. According to a 2019 report by the National Academy of Medicine, 34 to 54 percent of all nurses and physicians have “substantial symptoms” of burnout, as do 45 to 60 percent of medical students and residents. A 2020 report by Medscape finds the rates highest among urologists and neurologists, lowest among those in public health and preventive medicine. Others find rates highest among emergency room physicians (70 percent) and general internists. Across the board, women doctors report more burnout than men.

According to the AMA, burnout levels are “much higher” among physicians than among other workers in the U.S. and still rising. A study it conducted with the RAND Corporation sought to identify why. Topping the list is the steady growth of bureaucratic barriers to high-quality patient care imposed by healthcare systems, foremost among them cumbersome means of medical charting. Also taking a significant toll are insurer refusals to cover services physicians find to be medically necessary. Of course, burnout bleeds far beyond the well-being and life satisfaction of individual doctors to affect their personal relationships, their families, and the care of patients. It is also a source of medical error, now the third leading cause of death in the U.S.

The signs of burnout so overlap with those of depression that not all observers make a distinction between the two. Burnout may in fact be a more socially acceptable way of acknowledging feelings of hopelessness and despair among doctors. It shifts some of the onus of affliction away from mental health onto the power and persistence of stressors, lessening personal stigma.

“Lurking behind burnout is the possibility of an undiagnosed psychiatric illness, in particular depression,” says Michael Myers, a professor of clinical psychiatry at SUNY Downstate Health Sciences University in Brooklyn who specializes exclusively in the care of physicians—and subspecializes in physician suicide. He points to studies showing that the rates of depression in doctors and medical students are higher than those in age-matched controls. Rates of depression start climbing in med school and then take a big leap upward during residency training. In part, says Adam Kaplin, an assistant professor of psychiatry and behavioral sciences at Johns Hopkins, that’s because residency training generally coincides with the peak age of onset of mood disorders. But medical training appears to be unique in the stresses it supplies.

Beyond Burnout

Wendy Dean believes the difficulty doctors are experiencing goes far deeper than burnout, disrupting doctors’ sense of purpose, their source of meaning, their very identity. In four to six years of medical school, three to five years of residency, and often a few more years in a specialty fellowship, they don’t just acquire knowledge and skills, they absorb an obligation to protect the well-being of patients. The way doctors are asked to practice today, Dean and others observe, is in direct conflict with their deepest values. The result is the profound distress known as moral injury.

Over the past decade or so, doctors have gone from being independent practitioners to employees of healthcare systems, some owned by hospitals, some by insurance companies. Venture-capital and private-equity firms—which demand annual returns of 20 percent or more—have moved into medicine, buying up and operating physician practices at an accelerating rate, according to a recent report in JAMA. The AMA finds that employed physicians now outnumber self-employed ones.

One result, studies show, is that profits often come before patients, with the business of medicine divorced from—and controlling—clinical care. “What my patient needs, I now have to negotiate,” says Dean. The number of costly procedures goes up, but no one has yet shown that quality of care goes up too. Instead, doctors are squeezed, typically placed on tightly controlled schedules, with patient quotas to fill that drastically curb their time with each one to 15 or 20 minutes.

It’s not just that there’s hardly time to take a patient’s history, which often holds the biggest clues to what’s wrong, and the narrative telling of which seals more than a medical bond. But much of that time is spent turned literally and figuratively away from the patient, continuously itemizing and medical-coding into the computer every flick of the stethoscope and every microunit of observation in order to maximize payment. The electronic medical record (EMR) doesn’t just suffer from “note bloat,” doctors say, it’s become a billing document. And it gets in the way of care; patients get splintered checklist attention rather than holistic observation.

What gets sacrificed in the transaction are the very things—the hunger to know the person, discover what’s wrong, and find a fix—that make medicine so satisfying for practitioners as well as for their patients. “The connection with patients is absolutely a two-way street,” says Simon Talbot, a trauma surgeon at Brigham and Women’s Hospital in Boston and co-author with Dean of a well-read 2018 article describing today’s medical malaise as moral injury. “Patients want to be heard and understood. What gives us incredible satisfaction is sitting down with somebody and having that longer conversation that helps us provide the best care possible.”

As your doctor turns to the screen, you, dear patient, undergo a metamorphosis. You shed your humanity and are reconfigured as a profit center, a repository of RVUs, or relative value units. RVUs are a highly complicated metric of how much work and how many resources go into, well, servicing you. The calculus for care originated with Medicare, as a way to determine fees for physicians, but its biggest effect may be acceleration of the corporatization of medicine. Widely adopted by hospitals and healthcare systems, RVUs also serve as an onerous performance measure for doctors, who are pushed by those with no background in medicine to amp up their RVUs. Physicians are still reeling from how alien their own environment has become.

Talbot calls it death by a thousand cuts. “When you’re turning away from every single patient and looking at your computer screen instead of having a meaningful interaction, you begin to feel you’re not able to do the job.” Over 20 years of delivering primary care at the University of Chicago, Alex Lickerman found himself increasingly apologizing to patients. Hamstrung by the amount of time he could spend with them yet knowing they expected him to figure out their problems, “you feel as if you’re failing, and it’s your fault. It’s not that you can’t figure out what’s wrong; you don’t have the time to do it. I was apologizing all day every day for the failure of the system.” Four years ago, he left the university to set up ImagineMD, a new model of direct primary care.

And so, to the high cost of healthcare in the United States, add one more thing: the spectrum of distress that shows up as depression, burnout, moral injury, and physician suicide. “People who have something to contribute no longer feel they can, or it comes at too high a personal cost,” says Talbot. “Physicians are in the trenches with patients,” as much victims of the system as patients are, adds Hopkins’s Adam Kaplin.

“The doctor-patient relationship has been protective for us,” Kaplin explains. “It’s provided our purpose. Patients come because they depend on us to help them. Now it’s just a business. We’re losing our soul as a profession.” The physician-patient relationship may explain why some studies show that anesthesiologists have the highest risk for suicide. “Nobody sends them Christmas cards,” says Kaplin. The healthcare system, he concludes, “isn’t working for anyone.”

Sympathy for the Devil

Go ahead and say it: It’s hard to feel sympathy for doctors. They’re seen as a privileged class. They make more money than most people. They enjoy a high level of status.

On the flip side, they are quick to point out, they’ve given up their 20s to study, they undergo training that’s so demanding it assaults their DNA, they’ve acquired more debt than most—an average of $200,000 to $400,000—and their work lives are “hellacious.” Talbot typically starts at 6a.m. and finishes at 10p.m. If doctors’ lives don’t look so hard, it’s because patients don’t get to see the five patients waiting in the ER, the two in the ICU whose condition is deteriorating, and the mountain of lab results yet to be viewed and analyzed.

“When a doctor is driving around in a BMW and complaining, sympathy is a hard sell,” Talbot concedes. But to understand, he says, “you have to go back to the beginning.” The vast majority of those who go to medical school are there because they want to do something bigger than themselves, something meaningful, something to help other people.

It’s that very deeply ingrained desire to do the right thing—the foundational medical ethic—that is now being “cynically manipulated” by corporate medicine to hold the healthcare system together, contends internist Danielle Ofri, a clinical professor of medicine at New York University and an attending physician at Bellevue Hospital. In an op-ed in The New York Times, she explained that patients present with increasingly complex disorders, many of them chronic, requiring more management and medications, and creating more complications, all of which have to be handled in less and less time. But administrators know—and rely on the fact—that doctors will overextend themselves, that they’d sooner sacrifice themselves than walk away from a patient. It’s “not just bad strategy,” she observes. “It’s bad medicine.” In the end, patient care suffers.

“We get it from every side,” says Dean. “Patients are angry with us. Employers are angry and demanding. Insurers have ridiculous expectations, and regulators place expensive constraints on practice.” Malpractice insurance, for example, ranges from $15,000 to $50,000 a year, just for exercising one’s license. At $50,000, there’s little chance of forgetting that your first commitment is to the well-being of patients.

“Suicide Sundays,” Terri Cooper* called them—the day of the week when, after crashing on Friday night and sleeping straight through Saturday, she realized her increasingly grueling routine was about to start all over again. It wasn’t even grimly funny. She carried a handgun in her purse.

She loved her work as a palliative care physician at a large hospital, the team she worked with, and the patients, largely helping them handle chronic conditions that were not immediately life-threatening but were never going to remit. “That kept me going,” she says. But after a team member left, she was regularly working 12-hour days, squeezing in the documentation as well. She gave up workouts. She gave up massages. She even gave up going home. “I was either working or getting ready to go to work. Sometimes I slept on the office floor just to save an hour of commute time. I sacrificed the well-being of my marriage. Miraculously, it survived.”

When she asked supervisors for help, she was told to figure it out. And when she complained, she was deemed “unprofessional.” Exhausted and feeling hopeless, she felt her job was killing her—“but not fast enough. I thought about hurrying the process. I contemplated whether to shoot myself in the parking lot or in my office—which did I want to be the last thing I saw before I died?” Then came a day worse than the others. “I was in my office. The gun was in my purse. The next day I knew I had to leave the gun in the car. Down the line, I decided to take the gun out of the car and not have it with me at all. I needed to put more distance between me and the means.”

What saved her, she says, were her dogs, “being responsible for them.” And quitting. Last year, after 15 years at the hospital, on the service she implemented, she left to start a private outpatient practice ministering to people with serious illness and chronic organ failure. “I help people have a good quality of life. A lot of doctor-patient relationship goes into helping patients explore how to manage their limitations. The result is that my patients spend maybe 10 percent of the time in the medical system instead of 90 percent.”

A Profession of Perfectionists

Whether it’s called depression, burnout, or moral injury, how did it come to this, to doctors plotting their own death? For the most part, they’ve always had the means. What’s especially pushing them over the edge now?

It’s never just one factor, says SUNY’s Michael Myers. It starts with who becomes a doctor in the first place. Not everyone who applies to medical school gets in; on average, only 7 percent of applicants are accepted, and as applications climb upward, acceptance is getting tougher. The competition to get in puts heavy pressure on prior academic performance and high scores on the MCATs, the medical school admission test.

Academic achievement is scarcely enough, says Myers, who regularly interviews applicants. They tend to be accomplished in many ways, from athletics to musicianship. In order to gain such early expertise, they become practiced at delaying gratification and ignoring discomfort. Typically, high degrees of competitiveness fuel their drive to excel—and a tendency to deny distress and keep vulnerabilities hidden.

But perhaps the most distinguishing feature of their mental makeup is perfectionism, says Myers. Physicians as a group tend to be highly self-judgmental. Make a mistake, or fail to live up to expectations in some way, and they crucify themselves. What’s more, the hierarchical organization of medical training supplies plenty of criticism and correction from above, and many claim that in some specialties, such as surgery, these verge on abuse. Even so, perfectionism is a harsh mental master in its own right, not simply because the goal is always out of reach, but because it brings an inescapable focus on shortcomings real and imagined—and nonstop negativity is a well-paved path to depression. Plus, it locks people into constant comparison with others.

Perfectionism has its upside, however. It fuels the acquisition of knowledge and technical skills, of enormous value in the ever-expanding information base of medicine. Too, there are usually small victories to be celebrated along the way. Once they are in the field, perfectionism will keep physicians awake until their notes are entered and lab results are checked. Future physicians are not alone in their perfectionism; it drives high-level performance in many domains, including dance. But medicine may be unique in that patients tend to demand perfection from their docs.

Medicine also attracts people with a strong desire to be in control. The impetus for autonomy is highly adaptive: Medicine carries with it a huge burden of decision-making and responsibility.

For many who go into the field, it’s a calling they’ve nurtured all their life. “We love science; we love biology,” says Alex Lickerman, “but we want that relationship with patients and the opportunity to be healers.” They enter with a strong sense of purpose. Studies show they bring with them higher levels of compassion than average in the population. “You can’t be indifferent to human beings if you’re a physician,” says Wendy Dean. “That’s what’s attracting doctors.”

Schooled by Stress

But there are few resources to help physicians when they falter.

Rahael Gupta was used to working hard and outperforming even her own expectations. Medical school, however, was “just something else. Every week you have 30 hours of lectures on material you have to memorize and be tested on, and if you don’t get a 75, you have to repeat the test, for which no time is allotted. It’s like constantly drinking out of a fire hose.” A Stanford graduate, she entered the University of Michigan med school “with a rich, well-rounded sense of self. But in that environment, you come to define yourself by the numbers you get at the end of the week.”

She lost touch with the things she’d previously enjoyed. “I became a version of myself I didn’t recognize”—chronically stressed, fragile, torn apart by little things. “I’d open a bill, realize I hadn’t paid it, and feel negligent, irresponsible, worthless. That’s not very adaptive when you’re trying to get through med school.” She had a hard time paying attention to lectures and studying. Brain fog, she called it—one part anxiety, one part sleeplessness, two parts depression.

Clarity came only after she stepped in front of a bus. She was walking home from the library to the “white-coat ghetto” that housed the med students, not long after failing her neurology

sequence. She didn’t feel worthy of being a doctor. She didn’t feel worthy of being loved. “I stepped into the street. I knew the bus hurtling through the darkness would not have enough time to stop. I imagined my head hitting the asphalt. I imagined the bus driver’s horror. It would be a catastrophe the trauma surgeons couldn’t salvage.”

But she also thought of her parents, and almost as quickly as she had stepped off the curb, she stepped back on. And realized she needed help. The care she got through Michigan’s well-regarded Depression Center was so life-changing that she switched her interest from orthopedic surgery to psychiatry. Now, in her first year of residency at UCLA, “I definitely work hard but I am passionate about having a meaningful career.”

There is an enormous amount of information to acquire about the normal and abnormal functioning of the human body. And the amounts and kinds of knowledge keep growing. As students sweat their way through medical school, they not only learn the intricacies of the organism, they internalize the culture of medicine. Two of the most important lessons they assimilate are to deny distress and to put their own needs last.

When he was a first-year student at the University of Western Ontario med school, Myers returned from a long Thanksgiving weekend to be greeted by his landlady with the sad news that one of his three roommates would not be coming back. He had died, in fact killed himself, his parents had called to tell her. A stunned Myers had no clue his classmate was suffering, and he struggled to understand.

The next day, with no word from the dean, he felt obligated to inform his peers and asked his biochemistry professor if he could make a brief announcement before the start of the lecture. With a quavering voice and wobbly knees, he did. No one was prepared for the harsh reality, not even the professor. “‘Let’s get back to the Krebs cycle,’ was all he could muster into the long silence,” Myers recalls. Five months later, another professor, at lecture’s end, mused that he felt sad every time he saw the empty seat in the front row the roommate had occupied. “So many of us felt, finally, someone’s going to say something. What he said was, ‘I feel sad that we didn’t fill that seat with somebody who was prepared to go the distance.’”

From med school graduation through the first year of residency, sometimes called internship, mental health takes a huge hit. That’s when trainees first deploy at bedside all that they learned in the classroom. Srijan Sen was always interested in the genetics of depression, the focus of his M.D.-Ph.D. studies at the University of Michigan, where he is now an associate professor of neuroscience. Fresh into residency at Yale, he couldn’t escape noticing how happy everyone was at orientation but so thoroughly depressed by November. In their first year especially, residents work long hours, experience significant sleep deprivation, and take on a new degree of responsibility for patients—huge sources of stress.

Scientists know that stress is the single biggest driver of depression and it interacts with genes in ways still unknown. The problem is that it’s hard to study genes and stress together because it’s impossible to predict when people are going to feel stressed. First-year residents, Sen realized, provide an ideal study population. For the last 12 years, he has been running the Intern Health Study, first with about 200 subjects, now up to 20,000.

Residency training also imposes other specific risk factors for depression. Chief among them is sleeplessness. Residents typically work 60- to 80-hour weeks and are often on duty for days at a time. And up to 80 percent of those with depression will have thoughts of ending their life, says Adam Kaplin.

“We have found that with residency training, rates of depression pretty consistently go up about five-fold,” says Sen. “At least 20 percent are depressed. About half have an episode of depression at some point during the year.” The AFSP reports that 28 percent of all residents experience a significant depressive episode that affects health and functioning during training, versus 7 to 8 percent of similarly aged individuals in the general population.

The stress interns endure is so intense, Sen finds, that it speeds up the aging of body cells by about six years. In a study recently reported in Biological Psychiatry, he and colleagues measured the length of telomeres, the protective caps at the ends of every strand of DNA in every cell in the body, as trainees entered residency and at the end of the first year. Telomeres undergo known rates of attrition over time and serve as markers of aging. But residency accelerates the process. “At the cellular level, these people are coming in as 26-year-olds and finishing the year as 32-year-olds,” he explains. Cross-sectional studies of other groups, including the military, suggest that accelerated aging is a feature of many intense training programs, but not to the degree seen in medical training.

The Guardians Are Resistant to Getting Help

It is hard to miss the irony that the guardians of our health learn well to take care of others but never look after themselves. The general denial of distress that can push them to the edge of their professionalism makes them resistant to getting help when they need it.

Physicians face real deterrents to seeking treatment, because disclosing a problem is itself problematic. They can lose their practicing privileges. Traditionally, state medical licensing boards take a punitive approach to doctors who have made a suicide attempt or even owned up to depression, says Peter Yellowlees, a psychiatrist specializing in physician health at the University of California, Davis. Questions on licensing applications asking about the presence of psychiatric problems or substance use make doctors afraid to get treatment. They don’t want to put their license at risk. But recent changes to application forms in many states have altered the language, asking physicians only whether they are currently impaired. A step in the right destigmatizing direction, but the changes aren’t universal, and, unfortunately, says Yellowlees, the culture of medicine has yet to catch up with them.

But at least as much stigma comes from within, and it similarly commands silence when a physician falters in any way. Doctors feel a sense of shame about needing help for themselves, says Myers, and their feelings of unworthiness manifest in a unique form of impostor syndrome. The internal script goes something like this: “Maybe they made a mistake letting me into medicine. I’m not like everyone else, who is healthy and robust. They should have screened more carefully to keep people like me out of the lofty ranks of medicine.” The failure of doctors to get their own depression taken care of also has a lot to do with the well-documented failure of physicians to recognize it in their patients, notes Kaplin.

As a chief wellness officer of the UC Davis health system, Yellowlees is carving out a new role at medical institutions—helping physicians acknowledge and handle the many sources of distress now demoralizing the profession. Independent of the work he does, the mere existence of the position is an open acknowledgment that the problems physicians are facing are not reflections of individual weakness but are more systemic in nature. “My main job is to change the culture of medicine,” he says.

In his 18 months on the job, he’s implemented programs that attempt to reduce the burden of the EMR, so that Davis’s 2,000 doctors don’t have to spend pajama-clad midnights at home updating their notes. But perhaps his most important innovation is the introduction of anonymous computerized self-assessment of risk for suicide. Just showing doctors evidence of their risk can stimulate them to get help—in a neighboring town, if they want to. “That’s often sufficient for intelligent people,” he says. But he doesn’t leave it at that. He employs a team of psychologists to follow up anonymously to encourage doctors to seek a referral. “More and more health systems are going in this direction,” he says.

He’s also put in place peer-support networks for doctors who experience some of the traumas inherent in health care. One is for those, primarily surgeons, who experience the death of a patient on the operating table, because, he says, doctors tend to put too much blame on themselves—a reflection of both the personal perfectionism they start out with and the professional perfectionism drilled into them during training. A similar program is planned for physicians who get sued.

Yoga Is No Match for Moral Injury

Wellness programs teaching many means of self-care are standard fare for burnout, and they are now being adopted in healthcare settings and medical schools. Exercise has its well-recognized virtues, but yoga is no match for moral injury.

“Teaching people to meditate, making them more resilient—the problem doctors are facing is not about the individual at all,” says Wendy Dean. “Doctors are caught in the double bind of taking best care of patients and meeting the demands of the system: Make sure that you have enough volume. Make sure you’re billing correctly. Make sure not to refer anyone outside the system. It’s impossible to serve two masters at once.”

Language is important. Burnout, says Simon Talbot, implies a lack of self-care skills. Moral injury implicates the environment physicians work in. Two years ago, Talbot was feeling increasingly stressed and decided to test himself on a widely used burnout scale. “I looked pretty bad, but like any good clinician I decided to be scientific about it. I read the literature.” He got a coach. He started yoga. He changed his diet. “I felt great when I was on the beach. But coming back to work on Monday mornings, I felt exactly the same as I did before. The environment was eating away at me.”

At the time, Dean was working for the Department of Defense, and Talbot had some grants through her office. They got to talking and realized there was a parallel with “wounded warriors.” Doctors were working hard but were unable to do what they felt was the morally right thing to do. “There is a place for mindfulness,” Talbot believes. “There is a place for yoga and resilience. But they are not reasonable ways to fix a structural problem.”

There are in fact no easy ways to solve a structural problem. Changing the culture of medicine is a start. But physicians believe that the burnout problem will be solved only when M.D.s are able to talk to their patients again.