by Megan Burbank: It started with a green light. Andy Meyer noticed it as he looked out from the house where he was staying on Beacon Hill,

as his own home underwent renovations to welcome a new baby. “We figured it was a traffic light peeking through the trees,” he said. “And we thought, ‘I wonder if we could walk there one night, if we have the time.’ ”

So Meyer, who is a lecturer of Scandinavian Studies at the University of Washington, set out with a friend, vowing to limit his use of Google Maps, and walked in the direction of the green light, hoping to find out what it was.

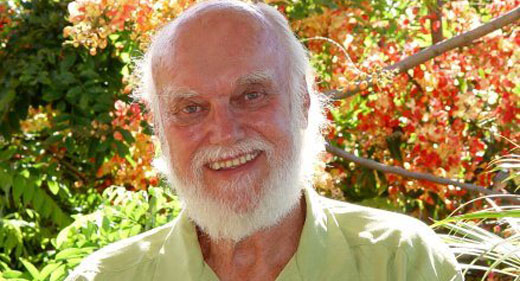

From left: Andy Meyer with friends Daren Salter and Scott Davis, Oct. 19, 2020, in Seattle. The three took part in a walking quest to a distant green traffic light, done in the spirit of friluftsliv, a Scandinavian concept that translates most directly to “free-air life.” (Ken Lambert / The Seattle Times) Less

Meyer’s quest is indicative of a new intimacy people are finding in their own homes and neighborhoods in the wake of massive closures and social-distancing practices adopted since the worldwide outbreak of COVID-19. But it’s also an example of the Scandinavian concept known as friluftsliv (pronounced “free-loofts-leev”), which translates most directly to “free-air life.” The term is attributed to Norwegian playwright Henrik Ibsen, but the concept of spending time outdoors in all seasons long predates him as a deep-seated element of life in the Nordic countries.

More expansive than outdoor recreation and less self-serious than outdoor adventure, friluftsliv describes “whatever you go to REI for,” said Meyer. “But in Norway, it’s this deeper concept of having space from other people, which is kind of a Norwegian thing to do, and then it has that sense of being able to wander freely outside.”

As we approach the first COVID winter in Seattle, a city with deep Scandinavian roots, friluftsliv may also be a helpful model for continuing to spend time outdoors during the coldest, darkest time of the year — something Norwegians have practiced since long before the pandemic.

“You also have the long dark winter, famously, in Scandinavia, and I think [Norway’s COVID-19 response and friluftsliv are] related in that way,” Meyer said. “You have already this sense of, there’s going to be a period every year where it’s going to be hard to be happy, where … the everyday life of doing the things you like to do is sort of interrupted for a time, under normal circumstances, by the changing of the season and the loss of daylight, and the cold that comes with it.”

In Norway, friluftsliv is so deeply ingrained into daily life that it starts in kindergarten. “Norwegian kindergartens are famous for being outdoors,” said Meyer. “In all weather, you will go outside for recess, if not for a good portion of the day.” (Outdoor preschools are Washington’s answer to Norwegian kindergartens; last year, the state became the first in the country to license them.)

A phrase you’ll find in Norwegian kindergartens, said Meyer, is one frequently associated with friluftsliv: “Det finnes ikke dårlig vær, bare dårlige klær!”

In English, it means “There’s no such thing as bad weather, just bad clothing.” It’s a cute phrase — in the original Norwegian, it even rhymes — but it belies a larger legal and infrastructural framework for outdoors culture within the Nordic countries.

Many Scandinavian countries have some version of a law that in Norway is called the allemannsretten, which translates literally as “every man’s right.” “Individuals have the right to travel or to be on land, so private property is real in a sense, but you can never stop someone from walking across your land … there is a right, and a legal structure for people to take advantage of the land,” said Meyer.

This centrality of outdoor activity extends even to public transportation, which Meyer discovered when, living in Oslo, he realized that it was possible to take the subway to cross-country ski areas that were lit at night to allow for skiing after sunset.

“In Oslo, you take any of those two subway lines out to the very end of the trail and you can put your skis on and go right out of the station, more or less,” he said. “And so you’ll find in the center of the city a bizarre number of people carrying around their cross-country skis to get on the subway and to head out to the trail.”

While that’s not an activity that’s replicable here, Meyer said he saw a similar spirit of access to the outdoors in Seattle’s Healthy Streets initiative, which starting in May closed off several local roads to traffic, allowing protected use for pedestrians and cyclists.

He noted, too, that in the wake of COVID-19, the Norwegian Trekking Association had adjusted its messaging to encourage people to seek out trails in their local areas rather than journeying farther afield — guidance that essentially matches what outdoor recreation authorities encouraged in Washington early in the pandemic.

We might not be able to take public transit to a cross-country ski trail, but the Northwest has long been home to Scandinavian communities and their athletic and cultural traditions, from the Swedish Club’s pancake breakfasts and Ballard’s Syttende Mai parade to the Kongsberger Ski Club, originally founded by Norwegian ski jumpers in 1954 (full disclosure: my dad is a member).

Another component of friluftsliv that feels right at home in Seattle is its emphasis on something akin to social distancing. In Ibsen’s original use of the term, he described “life of the free air for my thoughts” — meaning, said Meyer, “that being out there gave him space from other people’s thoughts … it’s an independence, or a sort of self-isolation that for him in that moment seemed to be very rewarding.”

There are echoes of the Romantic poets here, in the idea that being alone in nature allows for freedom and quiet reflection, and the emphasis on distance from other people resonates with certain stereotypes associated with both the Nordic countries (“How can you tell if a Finn likes you? He’s staring at your shoes instead of his own”) and the Northwest (the ever-controversial Seattle Freeze).

This pre-COVID social distance may even have contributed to both Norway’s relatively low COVID-19 caseload and the success of Seattle’s containment efforts compared to other major cities (especially considering the Puget Sound region’s status as an early hot spot for the coronavirus.)

But friluftsliv can also be social. Leslie Anderson, director of collections, exhibitions and programs at the National Nordic Museum, sees friluftsliv as a corollary to hygge. The Danish concept of “coziness and comfortable conviviality” was popularized in other countries through a number of books published over the past several years, and has shown up everywhere from marketing language for string lights to the Collins Dictionary’s words of the year for 2016.

While the two concepts are associated with different environments (hygge is internally focused) and different areas of Scandinavia, she said, “It’s about finding contentment … you can see a kind of shared fondness for both spaces and an approach to life where you have designated a space and a way of living with time to recharge.”