by Ed Prideaux: The growing legitimacy of psychedelics as therapies promises to transform how we view the extraordinary, writes Ed Prideaux…

LSD, or Lysergic Acid Diethylamide-25, is a chemical trickster. Mimicking the morphology of serotonin, it locks in the synapses of the brain’s 5-HT2A receptors to trigger a manifest wave in cognition: extraordinary ruptures in vision, patterns of thought, belief, and emotion.

Within an hour, the trickster’s games make themselves known. A sense of strangeness hard to put in words descends. Shapes and kaleidoscopes may appear and dance in synchrony. Synaesthetic connections – when you can hear or taste colours – could emerge. Depending on one’s dose, by the drug’s peak you may be thrown into an entirely altered dimension: a weird place filled with entities, snakes, designs behind-the-eyes, DNA strands, and a radically enhanced appreciation for art and aesthetics. Or something far darker.

Doblin’s world hummed, throbbed, droned. After floating through the campus dining hall, he made his way back to a private dorm for an inward-facing trip. Glancing at his friend – also surging on LSD – Doblin was struck by a fresh vision. Not merely deducing his co-pilot’s thoughts and emotions, Doblin could see them plain as day. His friend’s comfort, benefaction, warmth, were visible like arms and legs.

Transformative experiences aren’t like most experiences, even our most dramatic ones

Doblin wished he could feel so free. He was decomposing. In his own LSD rotoscope, Doblin had become a boy again – no longer the man – and the imbalance of emotion and intellect that drove his life in the everyday were sensible. Yet he was this way for a reason, Doblin realised. And this meant it wasn’t set in stone. He could change things. He could be free.

For the philosopher LA Paul, what Doblin experienced can be described as a “transformative experience”. These aren’t like most experiences, even our most dramatic ones. What makes them distinct is how they change a person: their preferences, ideas and identities are turned upside-down. When Doblin entered his first trip, he perhaps hadn’t realised that the next day he would not be the same.

Afterwards, Doblin knew he was on to something. He’d take more trips – many of which were destabilising – but the essential promise was clear. Evangelising the therapeutic potential of psychedelic drugs became his life’s mission.

After taking psychedelics in the 1970s, many people like Rick Doblin felt changed (Credit: Getty Images)

Doblin is today the founder and executive of a non-profit organisation called the Multidisciplinary Association for Psychedelic Studies (Maps), which aims to bring psychedelic drugs closer to mainstream use in medicine and beyond. It advises scientists how to conduct trials and win funding, as well as working closely with regulators.

Now the efforts of Doblin and others are finally paying off. In the last 10 years, psychedelic drugs like LSD, magic mushrooms, DMT, a host of “plant medicines” – including ayahuasca, iboga, salvia, peyote – and related compounds like MDMA and ketamine have begun to lose much of their 1960s-driven stigma. Promising clinical trials suggest that psychedelics may prove game-changing treatments for depression, PTSD and addiction. The response from the psychiatric community, far from dismissive or even sceptical, has been largely open-armed. The drugs may well mark the field’s first paradigm shift since SSRIs in the 1980s.

The “psychedelic renaissance” promises to change far more about our societies than simply the medical treatments that doctors prescribe

In 2017, for example, the US Food and Drug Administration designated MDMA a “breakthrough therapy“, which meant it would be fast-tracked through to the second stage of Phase-3 trials. Doblin, whose organisation was instrumental in achieving the designation, hopes it will achieve FDA approval by 2023.

Psychedelics remain Schedule-1 drugs federally in the US and Class-A in the UK, but rules are relaxing. Along with Austria and Spain in the EU, psilocybin mushrooms have been decriminalised in Washington DC and a host of other US cities, and legalised for therapy in Oregon, where LSD has also been decriminalised. A California bill to decriminalise LSD and psilocybin passed several crucial committee stages and will be decided next year. A vote to federally sponsor psychedelic research recently made its way to Congress.

In anticipation of this shift, psychedelic drug developers and clinical providers are attracting significant investment. Business reports describe “psychedelic euphoria” and a “Shroom Boom“.

This phenomenon is known as the “psychedelic renaissance” – and it promises to change far more about our societies than simply the medical treatments that doctors prescribe. Unlike other drugs, psychedelics can radically alter the way people see the world. They also bring mystical and hallucinatory experiences that are at the edge of current scientific understanding. So, what might follow if psychedelics become mainstream?

This wave of psychedelic enthusiasm in psychiatry isn’t the first. They were originally heralded as wonder drugs in the 1950s.

Across some 6,000 studies on over 40,000 patients, psychedelics were tried as experimental treatments for an extraordinary range of conditions: alcoholism, depression, schizophrenia, criminal recidivism, childhood autism. Participants included artists, writers, creatives, engineers and scientists. And the results were promising. From as little as a single LSD session, studies suggested that the drug relieved problem drinking for 59% of alcoholic participants. Experimenting with lower, so-called “psycholytic” doses, many therapists were amazed by LSD’s power as an adjunct to talking therapy.

For many years, psychedelics were difficult to study in scientific trials (Credit: Getty Images)

It wouldn’t last. By October 1966, LSD was banned in California, with federal restrictions to follow in 1970 under the Controlled Substances Act. Several alarming myths made their ways into government campaigns: claims of LSD-induced chromosome damage, mutant babies, that tallying five, six (or seven) trips made you “legally insane”, were propagated to school kids just like Doblin (although he’d only shirk the warnings in time).

This affected science, too. Apart from a handful of remnant groups in Canada and the US, the entire field of psychedelic science would dry up for decades. Regulators restricted access. Funders lost appetite. At the height of the crackdown from the 1970s to the 1980s, Doblin’s attempts to launch psychedelic research led to closed doors and real difficulty securing jobs.

Conventional narrative traces the crackdown to the career of Timothy Leary, a Harvard scientist who became the counterculture’s biggest proponent of LSD in the mid-to-late 1960s. A scandal at his Harvard Psilocybin Project in 1963 – in which his co-director was accused of dishing out psilocybin to undergraduates – would mark the first shots of a more sensationalist reaction in the media. Soon after, regulators would grow distressed by LSD’s black market currency “outside the lab”, which Leary’s post-Harvard advocacy – including claims that LSD could give women “thousands of orgasms” and excite revolution against the establishment – did much to furnish.

That’s not the whole story, though. Some medical historians pin the blame for the backlash on the rise of the Randomised Controlled Trial (RCT) methodology. This is now the standard way to run clinical trials, and its introduction raised questions about just how scientific “psychedelic science” really was among regulators. RCTs involve comparing two groups of people: one which has taken a drug, and another which has not. The participants aren’t meant to know which group they are in, but that’s difficult with psychedelic substances.

The Good Friday Experiment of 1962 – a session held in a church with seminary students to test psilocybin’s capacity for inducing mystical experiences – provides an illustrative example. One half of the subjects were given the active drug, the other a placebo (and all double-blinded), yet within 30 minutes it was plainly obvious who’d got which. Those dosed wandered around the grounds in a daze envisioning God, one of the participants told me – while the placebo group (including him) just “twiddled their thumbs and read the hymnal”.

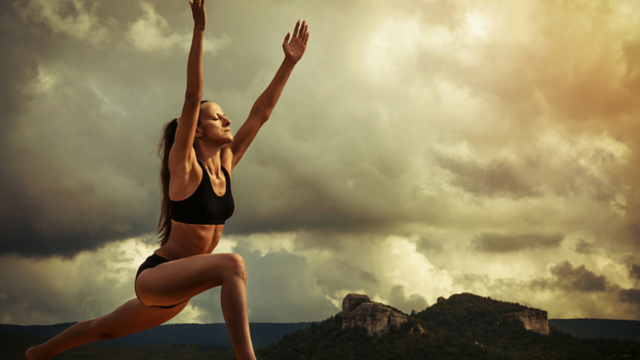

Psychedelics can change a person: their preferences, ideas and identities (Credit: Getty Images)

Between the 1980s and mid-2000s, flares of change amid the crackdown were seen. But the recent psychedelic renaissance has blown the doors off. It began with a landmark study in 2006 at Johns Hopkins University, headed by Roland Griffiths: a scientist who’d made his name studying caffeine. Griffiths and his co-authors attempted a replication of the Good Friday Experiment of more 40 years before. The results were striking.

“It is remarkable”, Griffiths wrote, “that 67% of the volunteers rated the experience with psilocybin to be either the single most meaningful experience of his or her life or among the top five most meaningful experiences of his or her life.” In other words, rivalling the profundity of marriage, childbirth, career highs, and other deep rites of passage.

While the challenges of conducting robust clinical trials have not gone away, regulators are now more open to psychedelic trial results than they once were.

The shifts in the cultural value and meaning of psychedelics in the last decade have been remarkable

Meanwhile, private clinics are beginning to open around the world. Awakn, a clinic in Bristol, offers infusions of ketamine as a treatment for depression, PTSD, eating disorders and addiction: while not classically psychedelic like LSD, high doses of ketamine can trigger powerful visionary experiences with therapeutic potential.

As the anthropologists Tehseen Noorani and Joanna Steinhardt write, “there are still limits to the enthusiasm for psychedelic healing. Still, the shifts in the cultural value and meaning of psychedelics in the last decade have been remarkable”.

If current trends continue, it may be a matter of time until psychedelic-assisted psychotherapy is green-lighted by regulators. In a decade’s time, might clinics and hospitals feature Psychedelic Session Rooms kitted out with cushions, incense, candles and paintings? Will doctors prescribe pills of psilocybin or LSD, manufactured by big pharma, with side effects including “ecstasy”, “changes in metaphysical beliefs”, and “acute panic”? Could we see the high-street version of psychedelic clinics – perhaps with names like “Pala”, “Indigo” or “Oasis”?

It’s difficult to know how it will play out, but if therapeutic psychedelics become more common, it may be only the start of a significant transformation in cultural and scientific attitudes.

Psychedelic culture

The psychedelic renaissance in medicine has been running parallel to a broader mainstreaming across culture, which the drugs haven’t experienced since the early 1960s. In Europe and North America, recreational use is rising – with use of LSD rising by 50% from 2015 to 2018 in the US – psychedelic-themed media are getting popular, influencers and celebrities are emerging as users, and the drugs are de-stigmatising in a way that their pioneers could likely never have foreseen.

Some have suggested calling the drugs “ecodelics” due to their propensity to connect a person to nature (Credit: Getty Images)

This mainstreaming has changed who is having psychedelic experiences, says Erik Davis, a writer and long-standing psychedelic commentator. Psychedelics in the 20th Century were confined to underground groups: hippies, hackers, Silicon Valley, spiritual communities, rave culture, environmentalists. Nowadays, though, appetite is coming from unexpected groups: wellness communities, hip hop culture, the political right, cryptocurrency enthusiasts, Wall Street traders, financiers, and everyday people looking to remedy their mental health.

It’s possible that we’ll soon see the effects appear in broader culture, just as we did in the music, writing, art and politics of the 1960s and 1970s. Yet it’s unlikely that any psychedelicised culture will look the same – nor feel the same to psychedelic users – because the world we live in now is so different.

To understand why, it helps to draw on a concept proposed by the social scientist Ido Hartogsohn, called the “collective set and setting”. One part of a drug experience depends on immediate individual factors – personal mindset, local environment, or the presence of others. But broader social forces make an impact too: the zeitgeist, media headlines, bigger cultural conversations. The 1960s had an entirely different “collective set and setting” compared with today. People didn’t just live differently, they tripped differently, too.

How might a major societal shift like, say, climate change feed into people’s experiences?

Consider all the different influences of the present day. Technology and artificial intelligence. Political conflict. A broader sense that society is heading in “the wrong direction”. The surveillance state. Off-the-record, one scientist I interviewed has already observed an emerging trend of “apocalyptic” trips, and not least during the broader pressures of Covid-19. “Messianic” trips are emerging in parallel: experiences in which one glimpses their own personal salvific role in effecting systems change.

How might climate change feed into people’s experiences? It depends on the individual, but when consumed in the right context, the drugs can significantly enhance one’s connection to nature. One of the most famous examples in this vein is the co-founder of Extinction Rebellion, Gail Bradbrook, who was inspired to start the movement by an experience on iboga.

For this reason, one social scientist has proposed calling them “ecodelics”. Another researcher interviewed for Vice magazine raised the idea of bringing pro-environmental cues to psychedelic sessions – the idea being to leverage the mind’s pivotality to increase nature-relatedness, and even dampen climate change scepticism.

Mystical experience

Under the surface, a still-more radical effect is appearing. In clinical trials and recreational use alike, psychedelics often produce states of “mystical experience” or “ego dissolution”: a peak consciousness characterised by bliss and goodwill, interconnection, a sense of the “sacred”, a possible “loss of self”, or even encounters with spiritual entities and God(s). What happens if more people start having them? And how might we understand their nature better than we currently do?

For researchers, the mystical experience is core to how the drugs produce such impressive results. It’s seen all the time in papers and reports. The greater the mystical experience, studies suggest, the greater the derived therapeutic benefit. Questionnaires to measure, track, and better-understand the mystical experience are proliferating.

Some believe that science alone is not equipped to help society understand the effects of psychedelics (Credit: Getty Images)

But science and psychiatry have cast suspicions on the mystical experience for centuries. “Even at the optics level, it’s a horrible name,” says Matt Johnson, a psychedelic scientist at John Hopkins University, “because ‘mystical’ sounds like you have a crystal ball and you’re casting a spell. For some people, it draws up a connotation of the medieval.”

This means that despite the role of spiritual experience in the cultural fabric – underpinning epiphanies of science, art, and religion for millennia – they have been chronically under-studied. People are reluctant to share their stories for risk of stigma, pathology, or diagnosis. Losing one’s sense of self, for example, may be diagnosed as “depersonalisation”, and a transformative shift to spiritual beliefs may be interpreted as the florid outpourings of a mental breakdown.

Outside psychedelic usage, more people have had mystical experiences than you might think. From 1962 to 2009 – the last year of available data – the number of Americans who reported a lifetime mystical experience more than doubled to half the population.

With this in mind, researchers may need to get better at understanding how they work and what they entail. For example, the notion that there is a single defined mystical experience at all has come under question. It’s not obvious how its core traits – the boundless, sacred, timeless, blissful – piece together. “There’s a good chance those are going to occur together, but just because something occurs together doesn’t mean it’s part of the same thing,” says Johnson.

As the author Jules Evans points out in The Art of Losing Control, the unitive character of the clinical mystical experience – that sense of losingone’s ego and becoming “one with everything” – also leaves out half the picture. A third of DMT smokers, 17% of LSD takers, and 12% of psilocybin users report encountering external entities. In neoshamanic rituals with ayahuasca, daime and iboga, these entities are anchors of the peak experience.

He received a clutch of octopus eggs that were laid inside his head. He interpreted this as an auspicious occasion

One subject in a study on ayahuasca, for example, describes a prototypical meeting: “He received a clutch of octopus eggs that were laid inside his head. He interpreted this as an auspicious occasion, and wrote that he believed the eggs symbolised a source of wisdom. He recognised the octopus as a benign ally right away.”

Psychedelics are often defined by the hallucinations they evoke (or, more accurately, pseudohallucinations), too. These hallucinations drove clinicians in the first wave of the 1950s to deem LSD a “psychotomimetic”, or psychosis-mimicking drug: a move that makes sense, as with its tendencies for casting extraordinary visions and hearing voices.

What might the future hold for psychedelics? (Credit: Getty Images)

If hallucinatory experiences were to be mainstreamed, not just de-stigmatised, this could mark a radical shift, says Davis, since they are more often associated with pathological conditions such as schizophrenia. He suggests it would be the culmination of the modern “neurodiversity” movement, which recognises conditions like autism or hearing voices as differences on a spectrum, and not discrete problems to be solved.

For Davis, understanding the extraordinary experiences of psychedelics shouldn’t – and can’t – be the sole domain of science. Some have suggested that literature and poetry may be a useful adjunct to scientific questionnaires. Others have called for theologians to join the table, too. After all, without a broader approach, he warns that some may undergo strange experiences that resist any “model” – and which could worsen their mental health more than enhancing it.

Coming down

Psychedelics offer something that few other things can: an experience well beyond what our everyday reality could conceive or expect. How the mainstream will handle its trip isn’t clear. Therapeutic mainstreaming may put big issues on the table, but one wonders whether the medical establishment can handle them alone. “The interest in industry, especially for clinicians in medicalisation, is to downplay all of that. What they want is a soothing, healing, restorative situation,” says Davis.

But the mystical, hallucinogenic and transformative experiences coupled with these drugs are likely to change far more than that for many. “Psychedelics are like philosophical probes,” Davis explains. “Even if you’re not a philosophical person, you have to suddenly deal with [things] the next day. ‘Well, what the hell was that? What do I make of that? Was I given a glimpse of true reality when I got the message to stop drinking alcohol? Am I going to take that seriously? Does that make me crazy?'”

For Rick Doblin – still in the echoes of that first transformative trip – the possibilities of psychedelics are far-reaching, and go beyond the clinical setting. With his organisation Maps, he wants to “legitimise psychedelics not just for patients but for all of us who are struggling with a world on fire… to try to make it so we don’t destroy the place. The tactic, you could say, is [to] medicalise it. But that’s not the end goal.”