by Jordyn Harrison: Most community gardens don’t last more than 10 years. But the Harambee Garden—at 12 years and running—has lessons to share…

rom 100 feet in the air, the parcel at 500 N. Waller Ave. in the Austin neighborhood of Chicago looks like the center of a donut. Surrounded by two churches, a fire station, a senior home, a town hall, a library, and a high school is a rectangular green space the size of five city lots. The land once stood empty and desolate, like many vacant lots in Chicago, but today, it houses beds of vegetables and fruits soaking in the sun and goats from a nearby farm resting under the shade of a tree. In the middle of the green space sits a gazebo with a hand-painted sign that reads, “Harambee! Gardens.”

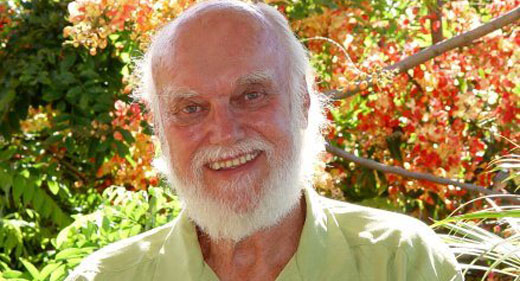

“From the start, it was something big enough that people would know about [it], partially because of the sheer size of it,” says Seamus Ford, co-founder of the garden, as he gives a tour on a cool October day, picking raspberries and pointing out tomatoes along the way.

Ford, a Chicago-born outdoorsman, casually walks through the garden with humble familiarity. Every now and then, he pauses, looking over the expanse of green in wonder, and recounts a detail about the garden’s beginnings.

In 2008, Ford, a special project manager for an educational company and a resident of the Austin neighborhood, became concerned about fossil fuel inputs and how food is grown.

“When fuel prices were going through the roof, it started to get really clear to me that there’s a change underway, and it could be a bad one if we don’t have answers to this,” Ford recalls. And that’s when he got into gardening. “I basically got rid of any grass, almost all the grass where I live, and built raised beds.”

Around the same time, he often drove by a vacant lot and began to feel a “siren call” to build a community garden. According to the DePaul Institute for Housing Studies, there are nearly 32,000 vacant lots in Chicago. Though many contain debris and trash, they can be an ecological and social opportunity. Planting a garden amid an otherwise empty lot is an opportunity that an increasing number of communities are choosing to pursue, but it is also one that requires hard work to sustain.

Ford learned that the land belonged to a neighbor and got permission to transform the grass lot into a garden. He then co-founded Root-Riot, an organization with the goal of creating a network of urban gardens “growing local food, fostering resilience, and reweaving the fabric of our community, one planting bed at a time.”

Now, 12 years in, the Harambee Community Garden can provide lessons about how it was able to last this long and where it’s headed from here.

Sowing Seeds of Change

In late spring of 2010, Ford was mowing the lot’s overgrown grass when Deandre Robinson, then a junior at Frederick Douglass Academy High School, walked across the street to ask Ford what he was doing. Robinson was thrilled with Ford’s answer, because students and teachers at Frederick Douglass had been discussing what could be done with that very lot, which had stood empty for more than 25 years.

“His face lit up so bright,” Ford says, recalling meeting Robinson 11 years ago. The resulting collaboration ultimately became the Harambee Community Garden, named for the Swahili word meaning “all pull together.”

Austin residents and members of surrounding communities organized workdays to begin transforming the vacant lot. Eager student volunteers from Frederick Douglass, like Robinson, helped with mowing, preparing the soil, and building the initial 30 garden beds—which grew to 58 the second year.

Interested gardeners, experienced or not, could rent a 4-by-8-foot raised garden bed for $40 a year or $100 for three years (which remains the price to this day). The cost covers materials needed for the garden, such as soil, compost, tools, and the beds themselves. People take home the food that is grown or give it away to the firehouse, the senior home, or other neighbors.

The garden has brought people from all walks of life together across the road dividing the Austin neighborhood from its more affluent neighbor, Oak Park. “Everybody was able to link up together and find common ground and make a new friend, find mentors,” Robinson says. A jobs program called Youth Guidance even got youth who were involved with local gangs to participate in the garden.

In the heat of Chicago summers, adults worked alongside youth to pull weeds and tend to crops. During the school year, they worked to make sure youth stayed on top of their studies and found other opportunities to add to their résumés. Adult gardeners helped Robinson study for the SAT and get an internship with local elected official U.S. Rep. Danny K. Davis. Ford even took Robinson shopping to get his first suit and tie.

Though Robinson doesn’t currently garden—he’s now a petty officer 1st class in the Navy and an entrepreneur—he credits his work ethic and consciousness of how food is grown to his time spent at Harambee.

“When people talk about Chicago, when they ask where I’m from, I’m never embarrassed. I’m very prideful, because a lot of the time, they don’t know us. … They don’t know our situation, our struggles,” Robinson says.

He believes the way in which the garden exposed him to new experiences as a teen can also influence the current generation of youth for the better.