by Anne Helen Petersen: I have spent so much of my adult life marveling at, obsessed with, and generally despairing re: the persistence of gendered norms around unpaid labor. By “unpaid labor” I mean: all the shit we do in and around our homes to make our lives work…

For a long time, I sat stewing in general confusion that so many relationships who ostensibly believe in the ideals of feminism (some queer, but mostly straight) almost always defaulted to an unequal distribution of labor — one that got significantly worse once kids entered the picture. And honestly? I find the entire situation pretty infuriating. For those who carry the bulk of the unpaid labor load, it’s a root cause of burnout — even and especially amongst those with full-time jobs with flexibility. I’ve seen this sort of inequality fester and create relationship-breaking resentment; I’ve seen people complain and then gradually, over the years, reconcile themselves to it. And no matter how much theory you read, no matter how much you believe in cultivating a different way of dividing labor than your parents or grandparents did, so many relationships (my own included!) fall into these bullshit rhythms and norms that, once established, are incredibly difficult to change.

Of course, there are a lot of reasons — some more understandable or excusable than others — why these divisions persist. And I get that. I know that. We know that. We know that some of them are policy-related and some of them are relationship-related and some of them have to do with the way that we’ve been socialized. But that’s also why I want to emphasize that the way we are modeling this distribution of labor, right now, for our kids and others’? It matters, and has significant bearing on the way that those kids, in turn, will engage in partnerships in the future. Saying “it’s too hard to change this now” and hoping for the best for the next generation isn’t a good strategy for, well, anything — and it’s certainly not a good one for trying to create a more equitable world.

Kate Mangino’s book Equal Partners: Improving Gender Equality at Home is the first book I’ve read that not only manages to diagnose why these divisions persist, even in couples that have the best intentions for them not to — and, just as crucially, offers compelling and practical methods for combatting them. These methods are not just for people in the actual relationship, but the people that surround them as well: parents, grandparents, siblings, peers, friends, and members of the community. Mangino acknowledges and emphasizes that these imbalances are not purely the product of personal decisions — and neither are their ramifications.

Equal Partners isn’t a book that’s just for straight couples, even though straight couples are statistically more likely to fall into unbalanced (and traditionally gendered) division of unpaid labor. It’s also not just for married couples, either, or couples with kids, or, frankly, people who are coupled. It provides ways to recognize what’s going on in your relationship, but also how to start a relationship on a solid, equitable footing.

So if you’re part of a relationship you think is equitable — read on, and you’ll either recognize yourself (or recognize that you’re not actually in a relationship as equitable as you thought). And if you’re in one that you know is not equitable, or not in a relationship but want one that is equitable — read on, and you might feel like there’s hope for its cultivation.

(We’ll also have a dedicated book discussion thread for subscribers in the Discord, to keep talking about strategies and implementation).

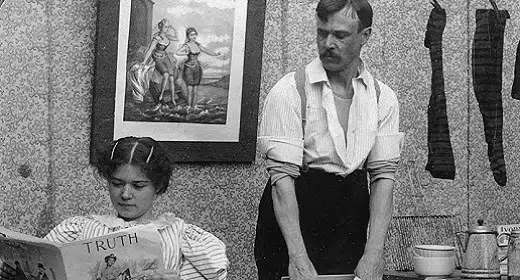

In the beginning of the book, you cite what I’ve come to understand as the stubborn, even cursed, 65/35 stat: that after significant improvement from our grandparents’ generation, the division of labor in the home has settled at around 65% performed by women and 35% performed by men. I love how you chose to illustrate this as, essentially, lost opportunity:

“Imagine all the extra hours men in this study can invest in other activities,” you write. “While his female partner continues to do housework for twenty, twenty-six, thirty-one more hours — he can devote this time to hobbies, relaxation, exercise, hanging out with friends, slepee, work and/or continued education. Essentially, he has the opportunity to do so much more with his life than she does.”

This description gets to something I see come up again and again when I talk to women, particularly mothers of younger children, about their lives: they feel like there is room for absolutely nothing other than care and work in their lives, even things they feel really passionate about. There’s just nothing left, not even a moment up for negotiation, and they can’t imagine a scenario in which that wouldn’t be the case, because the way they’re doing things feels like the only way things could be done. They often respond to the sort of suggestions of more equal partnership, or equal distribution of labor, with the reasons why it wouldn’t work, or why it’s much more efficient for them to just do it their way, and I get it: they have a system, it’s currently working, it just happens to also leave them with nothing left to give in any capacity. They’ve become so accustomed to the self-negation that other ways feel unthinkable. And, to be clear, I’m talking about women with feminist politics here, not people who think that division of labor is the way things should be.

My question, then, is a multi-part one: what makes the 65/35 so incredibly resistant to change, and what appeals are effective to women in those positions? That things don’t have to be this way, and indeed shouldn’t be?

I’ll start by answering your last question first, because I think this is one of the major roadblocks we face. And then work my way back.

Female-coded tasks are primarily routine and indoor: laundry, cooking, cleaning, caregiving. There is always something to do, day in and day out. Routine tasks are relentless. You might be able to order pizza and let dishes pile up for one day. But much more than that, and there is going to be a mutiny in your home. Indoor tasks also require a high level of cognitive labor. While you’re folding laundry, you’re also thinking about your shopping list. While you’re bathing kids, you’re working out how you’ll cover childcare during school break.

Male-coded tasks tend to be intermittent and outdoor: fix-it projects, accounting, yard and lawn, car maintenance. These tasks do not require daily attention. And while your neighbor might roll their eyes if the lawn gets long, there is no harm in skipping a week here or there. (Interesting side note – one would think men in urban areas would do more indoor tasks, since their outdoor space is limited. Not so. Broadly speaking, urban men just have more free time than suburban and rural men.)

To sum it up, the person doing intermittent / outdoor tasks has far more free time and far more flexibility than the person doing the routine / indoor tasks. Time and flexibility are incredibly valuable resources. With more time and the flexibility to do what you want, when you want to do it, the person doing male-coded work has a whole menu of opportunities (work, hobbies, education, sleep, friends, exercise, a second job, etc.), which are unavailable to their routine task performing partner.

So – to answer your question: what about women who know all this, but they think it is easier to just DO the work instead of starting the long, painful and potentially unsuccessful process of re-delegating tasks?

As a Feminist, my answer is always going to be, I think women should do what works best for them. If a woman is doing the indoor/routine tasks and is well aware she is doing more, but needs efficiency above all else to get through her days, then I would never suggest she should change her behavior. Everyone is the expert of their own life.

However, for the sake of this conversation, I would say that if an argument were to be made – it would be that not making a change and prioritizing efficiency over parity does support the status quo. And if you’re a Feminist and you value gender equality – then the status quo is probably not ideal. So, it might be worth sacrificing your own household efficiency for the sake of greater social change. And, I’ll pick this up below, but I am not advocating parity because it is just better for women. I’m advocating for parity because it is better for everyone… including men.

But I would like to make one suggestion, specifically speaking to those readers who are Feminist, but who need to prioritize efficentcy for the time being. First of all – no judgment, I get it. Second of all, be aware that through your actions you could accidentally perpetuate this concept that indoor/routine is “women’s work” and outdoor/intermittent is “man’s work.” And if you are a parent, this is problematic. So, to counter that, consider having some direct conversations with your kids over the years. Something like: This is the way we divide things in our house, and that leaves me to have more household responsibilities. To be honest, I wish it were different, but I have come to accept it for myself. However, I do not want you to assume the things I do are “women’s work” and things dad does is “men’s work.” Nor do I want you to accept this if it is not what you want. No chore is tied to gender identity, and families do things in many different ways. When you grow up, if you choose to have a partner, you two can decide how to approach your household and make your own rules.

This conversation frames behavior as a choice, and lets kids know they can make their own decisions later in life. Besides, we know that starting equitable patterns from the beginning is easier than changing once patterns are well established. So this leaves room for younger / new couples to be more intentional about how they approach their relationship.

Despite our individual behavior, I do think it is important for all of us to be able to articulate how the indoor/routine vs. outdoor/intermittent is not getting us to parity. Because one of the most common retorts I hear from men is some variation on, “we have equality in the home! I do the outside stuff, and my partner does the inside stuff. What’s the problem?” So, we all need to be able to address that, and hopefully educate those around us why old gender roles are nowhere near equal.

But to get back to your questions: Why aren’t we changing? If we are more gender aware than ever before in history, why are we stuck? (And we are indeed stuck. Household gender dynamics have not changed much since the mid 80’s.) I have two ideas.

- Separate and Not Equal: Just like in the above explanation, we divide household tasks and tell ourselves that we’re dividing them equally – but we are not. Male coded/female coded is lopsided = not equal. Indoor/outdoor is lopsided = not equal. Routine/intermittent is lopsided = not equal. Another popular one is Supervisor/Employee. Also lopsided = not equal. (More on this one below.)

- As Good as It Gets: We have indeed come a long way since the 1950s. There are not as many Don Drapers, Al Bundys or Homer Simpsons as there were 50 years ago. Most dads change diapers. Most men grocery shop. And so, I think a lot of people believe, because we have come so far, that this must be as good as it gets. Basically – if you think you’ve crossed the finish line, you’re going to stop running.

If people doing male-coded tasks think they’re doing half the work, and if people doing female-coded tasks think that this is as good as it gets… we’re probably not going to change.

You spend time on this subject in the book, but for this audience, can you talk about your decision to use the terms “female role” and “male role” when discussing behaviors, patterns, norms, etc? [I ask in part because this is something I find myself struggling with myself as well — and I’d love to hear you talk a bit about how this provides a way to talk more about queer or same-sex partnerships as well]

I struggled with what words to use for a long time. I’m not even sure I am thrilled with what I ended up on, but the manuscript was due and I got timed-out. I realize the language is a little clunky and I’ve had some criticism about that. But in the end, I had two strong values that I wasn’t willing to compromise on.

- Traditional gender norms hugely impact our lives. More so than any of us probably realize. To acknowledge that, I wanted to include the gender binary in my descriptors (instead of perhaps using words like caregiving and breadwinning) to draw attention to the fact that our social norms have very much been constructed within binary gender lines.

- I wanted to be inclusive. And by just writing about what men do or what women do dismisses same-sex and queer partnerships as well as different-sex partnerships with swapped roles. So I had to make room for people who, for example, do not identify as female but who do female-coded work.

So, I ended up with Male Role / Female Role. It was the best compromise I could find for 2022. I’d be interested in other suggestions!

I think most readers are deeply familiar with the concept of the mental load and the often invisible labor that accompanies it. Can you talk a bit about the role of the “noticer,” and how the labor of noticing often gets labeled as superfluous or as a “choice”? What makes this type of thinking and justification so noxious?

Invisible labor, cognitive labor – whatever we call it – can be extra burdensome in unequal relations, because the work is relentless and thankless. If we work our tail off doing something, then it is nice to get at least a thank you – some appreciation, some recognition. But since cognitive labor goes unseen, it is rarely recognized. We toil for no reward. So, when your partner does not recognize your cognitive labor, it hurts. What is that old saying about logistics? When they’re done well, no one says a word. When you make the tiniest mistake, everyone complains. I’d put cognitive labor in that same category.

In the book I also talk about the household Noticer. And in my mind, this role takes on two dimensions. Part of noticing is cognitive labor… noticing when the dishwasher is clean, noticing when you need to order more diapers, noticing when you’re out of milk, noticing that the shoes are all over the hall, noticing that the dog needs a groom, noticing that the front garden is full of weeds.

But I also think the Noticer does more, and we don’t talk about this extra stuff enough. So permit me to dive in here. The Noticer is often the person in the house who does all the nice little things: putting family photos around the home; buying pumpkins for decoration in October; organizing social events with friends and family. These individual acts might not make or break a household, but collectively, they are essential to making a home friendlier, more inviting, and more comfortable.

Sure, the Noticers often experience pleasure from doing these little things. (I know I do.) But I also think the Non-Noticers probably appreciate these warm touches more than they care to admit.

I also believe that this type of noticing work contributes to building social bonds. Noticers put family photos around the house to remind us of happy memories and those we love. Noticers decorate for holidays, because it connects us to tradition. Noticers organize events with friends and family to strengthen our social networks.

I didn’t write this next bit in Equal Partners, because it is something I’ve thought about since it went to print. But I believe Noticing is also linked to emotional health. Those feelings of coziness, safety, love, comfort, connection – all of those are potential ways to improve emotional health. We might not make that decision consciously – “I am updating the family photos to improve our emotional wellbeing” – but subconsciously, perhaps that is exactly what we are doing. Noticers care about others, and noticing is a way to demonstrate love.

Noticing is one of those deep values that is hard to get to, because it is buried under so many layers of gender norms. But I think it comes down to this: historically, Noticing is a female-coded task (because girls are raised to value and support social bonds) and the Noticer feels that they must do this noticing work; it is not a choice or an option. It is in our job description. It is required to make us a good parent, a good spouse, a good family member.

The Non-Noticer, however, is often dismissive of noticing work. Non-Noticers often label noticing work as unnecessary. I think this has roots in the fact that boys are raised to fix problems and move on; utilitarian.

So, you now have one person who is doing what they feel they must do, without thanks or appreciation. Noticers often feel dismissed, unappreciated, and eventually – resentful. And on the other hand, you have one person who is endlessly frustrated that their partner spends so much time and energy on something they perceive as gratuitous.

This fundamental disconnect leads to frustration for both people.

Where do we go from here? Well, I think recognizing that these behavior patterns have gendered roots is important. This might help us change the way we raise our kids. Perhaps in the future, the expectation will be that both partners, no matter their gender identity, will do at least some noticing in the home.

And for those of us adults? I suspect the key to real change is finding balance. Non-Noticers could do more: they could say thank you, they could acknowledge and appreciate the work being done to make their lives better, and they could always start noticing themselves.

And this is a slippery slope, I know – but I am going to say it. I think Noticers need to do less. Let’s face it, Notices can go overboard. I say this as a Noticer who goes overboard all the time. I think sometimes when 60% is adequate, Noticers feel compelled to go for 99%. And that could be time and mental capacity that could be used elsewhere, including for leisure or activities a Noticer is passionate about (in other words, not just more ‘work’).

I think in a truly equal partnership, both people must be Noticers. They both participate in the cognitive labor noticing, and they both participate in the household comfort noticing.

I loved your outline of the “reframing tactics” that couples use to justify the unequal division of labor — and I think readers will recognize them as well. Can you talk a bit about “the bossy wife decoy” and the “supervisor/employee relationship” in particular, and the stakes of maintaining each?

Thank you for bringing this up – the “reframing tactics” section is one of my favorite parts of the book.

I was inspired by Dr. Allison Daminger’s work. She researched different-sex couples and household work (she also coined the term cognitive labor) and found that when a couple who values gender equality has gendered behavior in their relationship, they have three choices: change their values, change their behavior, or “de-gender” their behavior so it doesn’t look like a gender issue.

No one wants to change their values – those are part of who we are. And changing behavior is hard and requires lots of time. So, not surprisingly, Daminger found that couples opt for #3.

This finding led me to think of all the ways couples “reframe” gendered behavior, so it sounds like something other than gender. I think these are critical to recognize, because these reframing tactics are part of why we perpetuate sexist traditions. And we can’t stop doing them if we don’t recognize them.

I offer six tactics in Equal Partners, but I’ll talk about the two that you mentioned: Supervisor/Employee and the Bossy Wife Decoy. I’ll use abridged excerpts from the book to explain each.

Supervisor / Employee: Conceptually, this tactic embraces comparative advantage. In a household with two working adults and not a lot of time, it is natural to want to avoid overlaps. So, some couples divide the household duties along management lines – one person assumes a supervisor role, and one person assumes an employee role. Both people have a job to do, and mirroring a workplace structure allows clear responsibility and accountability from both. The “manager” focuses on the cognitive labor, and the “employee” completes tasks as told. In the end, I find this reframing tactic unfair to both.

Unfair to House Manager: Managing a perfect employee can be a wonderful experience. But when the House Employee is not serious about their job, forgets half the tasks and messes up the other half, it creates more work for the House Manager. And there is no recourse. Is your House Employee always late to work? You can’t give them a bad performance appraisal, demote them or dock their pay. Is your House Employee excelling at their work? You can’t give them a raise, a bonus or a promotion. (If your mind is drifting towards physical rewards or punishment, let me remind you that would classify as transactional sex.)

This puts the House Manager in an impossible position; they can assign tasks to their partner, but there is no accountability. They just have to put up with whatever they get. In the end, they give up and take on more work – just to get things done. Everyone knows that it is more trouble to manage a delinquent employee than just do the job yourself.

Unfair to House Employee: Organizational structure tends to assume that the supervisor has more expertise than the employee, and employees are expected to listen and follow instructions. We stomach these positions in our work environment, because we have no choice; we all need to work to earn money. Navigating work relationships is just part of modern survival. But who wants to live in a world where your partner is thought to know more about – well, everything – than you do? How is that at all romantic?”

Bossy Wife Decoy: Another reframing tactic is to use a decoy to make it look like your house is the opposite of the stereotypical gender divide; that the Female Role is actually the one in charge, setting the rules, making the decisions, and calling household shots. If there’s a bossy wife in the home, how could the Male Role possibly be slacking off? After all, he isn’t setting the rules – he is just following them. Do these retorts sound familiar?

· “She wears the pants in our family.”

· “Don’t ask me – go ask The Boss.”

· “I don’t make the rules, I just live here.”

· “Happy wife, happy life.”

These tropes perpetuate the notion of the bossy, overbearing wife. We’ve all heard these phrases; they usually come with a roll of the eyes and a shrug of the shoulders, reminiscent of the old laugh line about a ball and chain. In this light, the Male Role is the one we tend to sympathize with. The “sweet guy” who just tries to keep his partner happy at all costs. The man who repeats “yes, dear” ad nauseum and works to keep the peace in his home. This trope is not only perpetuated by men – people of all genders buy-into this role. I once saw a couple wearing matching t-shirts in a hotel lobby. His read “Vacation Financer” and hers read “Vacation Boss.”

This dynamic may speak to how a couple communicates, about their sense of humor, or about how they prefer to project themselves to others. But it certainly doesn’t correspond to gender balance in their home. In fact, it is quite the opposite. In my mind, those who pivot to the Bossy Wife Decoy are very likely participating in a traditional household balance. If it is the Female Role making rules, she is also the one likely doing all the work to operationalize and enforce those decisions.

It is also worth noting here that this reframing tactic is often used along with humor, and often in public spaces, which makes it uncomfortable to counter. Women who push back are often gaslighted. Their words are either “proof” of their control, or they are dismissed as being too sensitive. These are common ways that structural misogyny polices our actions, putting non-compliant women back in their place.”

TELL ME EVERYTHING ABOUT THE EP40. (Sorry this is very broad but I am obsessed with this section and would love the audience to learn as much about it as they can). Who are they, what did they have in common, what did their partners have to say about them?

I am obsessed with the EP40, too.

When I started this research project, I decided to focus my interview time with men who are already equal partners, or EPs. We all know what inequality looks like. I wanted to discuss, and hopefully start to normalize, parity.

I set out to find a diverse set of men that would give me a variety of perspectives. In the end, I identified and interviewed 40 men who came from fifteen US states and three Canadian provinces. Collectively they represented rural, suburban, and urban areas. Five men were in same-sex relationships and 35 were in a different-sex relationship. The EP40 had a range of education levels; several had a high school diploma and one had a PhD. Some earned a salary and some earned an hourly wage. These men identified as Black, Afro-Caribbean, Latino, Asian American, African, Native American and White; Jewish, Christian, Muslim, Bahai, and non-religious.

But they did have several things in common. All of them understood the power imbalance in our society that leads to gender inequity. All of them are intentionally trying to counter traditional gender norms. And all of them did half of the physical and cognitive labor in their household.

I’ll mention two big take-aways from my interviews:

- Anyone can be an equal partner. These 40 men came from incredibly different backgrounds. Only two of the EP40 came from families that modeled parity. TWO. Thirty-eight of them came from something other: single mother households, traditional households, violent or abusive households. But all of them ended up in the same place. Now, all of them had help, too. They didn’t necessarily find parity on their own – and I think that is also important to note. They were each influenced by someone along the way, but they all came to the same conclusion – they wanted to be an equal partner in their relationship.

- The EP40 are not giving anything up; they gain from being an equal partner. The men I interviewed rejected the idea that they were sacrificing, or giving anything up. Being an equal partner was their choice, and they wouldn’t want a life any other way. They were also very clear on the benefits to being an equal partner, which included a great relationship with their spouse, meaningful relationships with their kids, and a feeling of success for being fully competent in their home.

I’ll add some thoughts that didn’t make it into the book….

Interviewing the EP40 was an absolute joy. I sold my book in June 2020, and so many of those interviews took place during the first wave of pandemic lockdowns. It was a unique point in time; there was so much uncertainty and so much fear. I think we all needed someone to talk to – and my conversations felt very raw and very real.

Most interviews began by the EP telling me that they were just a normal person, with nothing to share. And then hours later, many of them wanted to get in one more story before we hung up. I loved learning about their childhoods, their kids, their partners, their work – I loved listening to stories about how they saw the world and how they fit into it. I cried during several interviews, and had many EPs cry too. I am grateful for each one of them – inviting me into their lives and sharing such personal information. And I remain in contact with many of them today.

Ah, before I forget – you asked what their partners thought of them. Well, their partners loved them! I mean, relationships are still tough. They told me about hard times and the usual arguments. The EP40 are not saints. They’re human, and often said or did the wrong thing. But overall – the partners deeply appreciated their own household parity. They knew they had a different kind of relationship than most people. And they were glad. They might get mad at their partner for this or that, but they didn’t resent them. There wasn’t any bitterness. There was always still a lot to do – but they felt like a team. They worked hard together, and felt exhausted together.

The book is really focused on potential solutions in a really refreshing way — like, we know that things are unequal, we’ve read about it ad nauseum, we also know that structural change is necessary, but we also need ideas for how to start making smaller changes in our own lives. (Advocate strongly for the macro changes, live in the micro, etc etc).

I find that I rarely ask authors to talk about these more basic/utilitarian solutions, because I find we, as authors, are often asked to create soundbites and “quick fixes” that elide the whole iceberg of work underneath real change. But! I am curious about access points: small conversations or practices that can get the ball rolling towards shaping more equal partnerships, and not just between partners, but at every level of community.

I’ve also read about inequality ad nauseum. But that was an important start. First, we had to define the problem, and convince the world of that problem. And I am grateful for the great journalism and research – especially during the pandemic – that got us to where we are today. But yes, now I think it is time we do something about it.

This is where my background in social change comes in. I’ve done this work for two decades now, and I know it works. Not just me, but everyone working in my field. We use social change theory in development projects all over the world. So there is no reason why we can’t employ social change theory in our own lives. After all, gender constructs are all learned. Which means we can unlearn them.

Now, I fully admit, unlearning gender norms is not easy. As you said, there is no magic sound bite. And I would be lying if I said anything other than this – behavior change requires time, hard work, uncomfortable dialog, patience and commitment.

The good news, however, is that unlearning gender norms doesn’t require extra minutes out of your day. Sure, I’d love people to take the time to read my book. But after that, change does not require two hours a week, or even two hours a month. I actually think that our mundane, everyday conversations – conversations we are already having – can be the greatest drivers of change. But we have to look for opportunities to engage. To use your words, we have to recognize the entry points. The last two chapters of Equal Partners are devoted to this concept.

I’ll give you a few examples that are not in the book. Both stories are true, but I’ll use pseudonyms to protect the identity of the people who shared these stories.

Helena and Clara are grandmothers, who recently had lunch together to catch up. Clara was telling Helena a story about her grandson, and ended by saying, “well, you know how boys are. They’re just messy. We can’t expect much more.” Helena recognized that as an entry point. But she also hates confrontation – so she remembered some suggested language from Equal Partners and quietly said, “You know, I don’t think I believe that anymore.” This led Clara to ask why – and the two friends ended up having an interesting conversation about gender stereotypes and children. Helena told me she wasn’t sure if she changed Clara’s mind in the end, but at least she was able to articulate her perspective. And she felt better about herself for saying something, instead of letting that opportunity pass her by.

Gareth is a Millennial male. Recently, his mother made an off-hand comment about how Gareth wasn’t handy – or at least, not as handy as his father. Gareth felt judged. But he recognized that as an entry point to conversation. So he calmly said, “I know that men are coded to do handy work around the house. And I admit, I’ve never been interested in that stuff. Not like Dad. But I don’t have any less value, because I like to cook instead of fixing stuff.” His mother immediately backpedaled, and agreed with him, and acknowledged that Gareth is no less of a man because he isn’t handy.

These entry points are critical because not saying anything is the default for consensus. If Helena didn’t speak up, Clara would have assumed Helena agreed with her statement about boys. If Gareth hadn’t said anything, his mom would continue thinking a man’s value was linked to his ability to be handy. Silence is a vote for the status quo.

If we are truly committed to gender equality, then we need to push ourselves to actually do something about it. And I hope my book gives people the information they need to initiate conversations around them, and start to make a change.

And this might sound cheesy to some, but I honestly believe this – if every one of us interested in gender equality recognized the entry points in our day to day life, and responded to 10% of them, we would make a huge difference.

Why 10%? Because I am realistic. Even I tire of pointing out gendered comments all the time. Sometimes it isn’t appropriate, and sometimes we don’t have the power to say something. (For example, few people feel comfortable pushing back on their boss’s or landlord’s gendered statement.) If you want to do more than 10%, great! But honestly, if each of us just took advantage of a fraction of the entry points presented to us, I think we’d start to see real change.