by Dylan Jones: Dylan Jones on Jimmy Webb’s Enduring Masterpiece…

“Wichita Lineman” sounds as good to me now as it did when I first heard it 50 years ago. It has never palled or suffered through overexposure. I never wince when I hear it.

Some neuroscientists believe that our brains go through two stages when we listen to a piece of music that we like: the caudate nucleus in the brain anticipates the build-up of our favorite part of the song as we listen, while the nucleus accumbens is triggered by the peak, thus causing the release of endorphins. Accordingly, they believe that the more we get to know a piece of music, the less fired up our brains will be in anticipating this peak.

This thesis starts to evaporate further when you consider that received wisdom says that the more complex a song is, the more it will endure. “Wichita Lineman” is anything but complex. It might have an unusual structure, and the lyrics might be particular, but it’s not exactly “Bohemian Rhapsody,” not exactly comparable to the type of intricate prog rock made by the likes of Yes, Camel or Emerson, Lake & Palmer.

I once read about a professor who ran a music-therapist program at a New York University. He said we hang on to songs because they are part of our “identity construction,” and that we are always trying to use them to get back to our lost paradise. What I certainly know is that I don’t tire of “Wichita Lineman” for the same reason I don’t tire of listening to the Beatles’ “Hey Jude,” Brian Protheroe’s “Pinball,” or Nick Drake’s “One of These Things First”—because it defies the injustice of repetition.

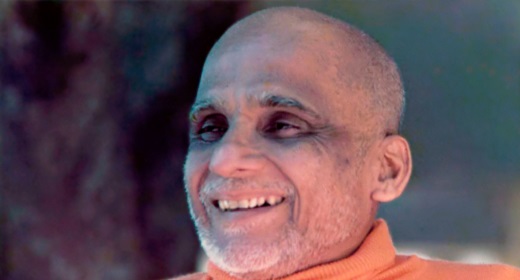

I know someone who heard “Wichita Lineman” before it had been recorded. Doug Flett, a songwriter friend of mine, was visiting a Los Angeles recording studio in the summer of 1968 when a young, Nehru-jacketed Jimmy Webb pushed his head around the door. Would Doug like to hear a demo of “Wichita Lineman,” this new song he’d written? Would he?

With his partner Guy Fletcher, Flett would go on to write “The Fair Is Moving On” and “Just Pretend” for Elvis Presley, “Is There Anyone Out There?” for Ray Charles, “I Can’t Tell the Bottom from the Top” for the Hollies, and “Fallen Angel” for Frankie Valli, but at the time had only just started writing. He was on a reconnaissance trip to LA to meet publishers and agents, so an invitation to hear a new song by one of the hottest songwriters in the industry was something of a gift.

Quick as a flash, Flett followed Webb into his own studio, where he was afforded the luxury of hearing Webb belting out his demo version of the song, complete with improvised coda. Even though Webb knew it wasn’t complete, he seemed proud of it. Maybe he was playing it because he genuinely wanted Flett’s opinion, although considering the hierarchy involved, most likely this was just a case of the master giving a masterclass to a novice (even though Flett was actually eleven years older than Webb). Flett was even blown away by Webb’s singing, which shows you how in thrall he was. “It wasn’t just the song,” said Flett. “It was the voice, a beautiful, haunting thing.”

The sucker punch of “Wichita Lineman,” the line that contains one of the most exquisite romantic couplets in the history of song—“And I need you more than want you / and I want you for all time”—could be many people’s perfect summation of love, although some think it’s something sadder and perhaps more profound.

The fundamental reason Flett liked the song so much was one particular line, the dying fall, the line about needing someone more than wanting them. For an aspiring lyricist, this was something else again. And all from the pen of a man who was barely 21.

While it’s often disconcerting to be stirred by language that resists comprehension, the ambiguity of a song’s words can often be its prime attraction. How many songs that you love, which you can sing along to on a regular basis, contain great swathes of unintelligible phrases, where the vocals appear to almost randomly skirt across the surface of the tune?

There is little ambiguity about the greatest couplet ever written. The punchline—the sucker punch—of “Wichita Lineman,” the line in the song that resonates so much, the line that contains one of the most exquisite romantic couplets in the history of song—“And I need you more than want you / and I want you for all time”—could be many people’s perfect summation of love, although some, including writer Michael Hann, think it’s something sadder and perhaps more profound. “It is need, more than want, that defines the narrator’s relationship; if they need their lover more than wanting them, then naturally they will want them for all time. The couplet encompasses the fear that those who have been in relationships do sometimes struggle with: good God, what happens to me if I am left alone?” Hann is certainly right when he says that it’s a heart-stopping line, and no matter how many hundreds of times you hear it, no matter what it means to you, it never loses its ability to shock and confound.

There is also another more prosaic interpretation of the line, however, one that mirrors Brian Wilson’s “God Only Knows,” in which Wilson says that while he may not always love the object of his desire, as long as there are stars above her she never needs to doubt it. Meaning: my love could not be greater, and no matter how much I need you, my love for you is so immense that it matters not one jot. Bob Stanley, the musician and author, says that the line is the most beautiful in the pop canon, “one that makes me stop whatever I’m doing every single time I hear it.”

“It came out without any effort whatsoever,” Webb told me:

I don’t remember putting any particular concentration behind it, which may be why it flows. When I started seriously performing in my later years, about twenty years ago, I moved east and I played all the big nightclubs in New York, and I think I was exposed to an audience that really appreciated the finer points of songwriting a little bit more than maybe the surfer guys that I grew up with. People would come up to me and say, “How did you write that line?” And I would say, “Excuse me?” And they would say, “How did you write that line, ‘I need you more than want you / and I want you for all time’?” I’d say, “I don’t know. It felt right, it seemed like a good idea at the time.” Then—and I’m being very candid with you—I began to notice it more and more, and then I had guys coming up to me after the show and saying it was the greatest line ever written. I’d laugh. Then it got to a point where a guy would come running up to me and say, “The greatest line ever written!” And I’d say, “Let me guess.” It became so pervasive it became like a meme. I have a black T-shirt I sell at my gigs that’s kind of a silhouette, kind of an artsy, nice picture of a lineman, and on the back it says, “I need you more than want you and I want you for all time.” And these T-shirts sell like hot cakes, they fly off the table.

I was trying to express the inexpressible, the yearning that goes beyond yearning, that goes into another dimension, when I wrote that line. It was a moment where the language failed me really; there was no way for me to pour this out, except to go into an abstract realm, and that was the line that popped out. I think the fascination comes from the fact that it just pushes the language a little bit beyond what it was really meant to express, because it could be deemed perfectly nonsensical—“I need you more than want you / and I want you for all time.” I mean, those are all abstract concepts, all jammed up together there. But that’s because it’s trying to express the inexpressible.

I don’t judge, but I evaluate a person’s sensitivity by their ability to respond to poetry. Not just my lyrics and not just James Taylor’s lyrics and not just Joni Mitchell’s lyrics. . .because when Joni Mitchell wrote “A Case of You,” she broke my heart, it was like someone swung a sledgehammer against a teapot. I still can’t say that line without losing control of my emotions. That was also a case where she was trying to express the inexpressible, so she had to push the language.

“It’s almost childishly simple, but it suddenly dawned on me that I was a conduit for all kinds of emotions that people were either incapable of expressing or unwilling to express. The song became the real e-mail—emotional mail. The songwriter is almost a trader in feelings. I realized somewhat later that I deal almost exclusively in the emotional wreckage of life. It’s where I live, and that can be really, really dangerous.”

“I was trying to express the inexpressible,” Webb said, “the yearning that goes beyond yearning, that goes into another dimension, when I wrote that line. It was a moment where the language failed me really.”

“Good songwriting is still important,” said Webb. “It is a continuing miracle that an art form so potent and influential in the emotional lives of human beings is available to virtually anyone who wants to enjoy it. There’s a subtext to classic hit songs, and that subtext is the common experience. By its very nature, it isn’t very easy to explain the intangible hook that fastens on to everyone.”