by Chris Kincaid: What will your final words be just before you die?

Japan has a long history of jisei, or death poems. Jisei is the “farewell poem to life.” These poems were written by literate people just before their death. One of the earliest record of jisei dates to 686 CE with the death of Prince Otsu, a poet and the son of Emperor Temmu, who was forced to commit suicide on false charges of promoting a rebellion.

Jisei was written in kanshi, waka, and haiku. Not all death poems are haiku. However, they are all in the short poem style (tanka). Kanshi is the Japanese word for Chinese poetry. Waka is a poem written in Japanese (as opposed to a kanshi). Finally a haiku is a poem that relies on two images divided by a kireji, or cutting word. Haiku consist of 17 on, which are different from our English syllables.

Like most haiku, jisei seeks to transcend thought and create an “Ah, now I see” moment. Jisei strives to connect the reader with the poet’s mind just as they are poised at the end. Haiku tries to remove our dualistic ways of thinking, the division between beauty and ugliness, life and death, future and present.

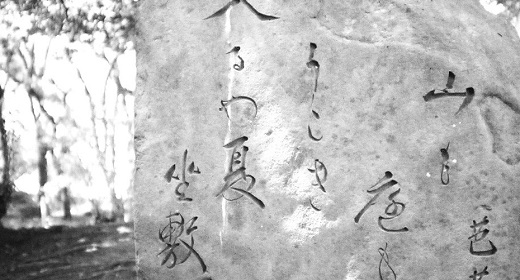

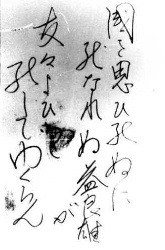

A Japanese soldier who died in a submarine Sept. 7th, 1944. Translation: This brave man, so filled with love for his country that he finds it difficult to die, is calling out to his friends and about to die.

In the Japanese language, according to Hoffman (1986), shi “death” is rarely used to reference a person. Instead, specific kinds of death are used: shinju, “lover’s suicide;” junshi, “warrior’s death for his lord;” senshi, “death in war;” roshi, “death from old age.” Death is linked to the type of life a person lived. Jisei is an extension of this idea.

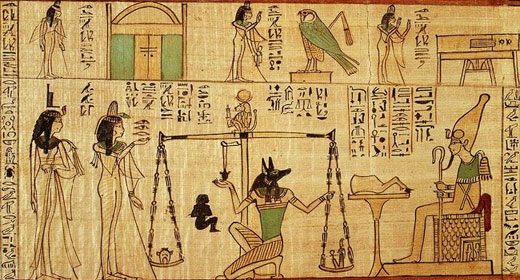

The images used to represent life and death changed over time. Early poems used flowers to represent the ephemeral world. Later poems, particularly those of the samurai class, added other images from nature.

Some jisei are dark while others are hopeful. They each reflect what is on the mind during the last days or moments of the writer. Acceptance is one of the key elements to jisei; the poem comes directly from Zen’s acceptance of life as it is, including the inevitability of death.

I have to note that our translations of these poems can obscure word play. In Japanese, the same word can have multiple meanings based on context. Many poets use this to advantage to build multiple layers of meaning. English translations lose out on this aspect of Japanese.

Here is a small selection of death poems:

There is no death; there is no life.Indeed, the skies are cloudless

And the river waters clear.–Toshimoto, Taiheiki (Chronicle of Grand Pacification).

I wish to die

in spring, beneath

the cherry blossoms,

while the springtime moon

is full.–Saigyo (1190).

Inhale, exhale

Forward, back

Living, dying:

Arrows, let flown each to each

Meet midway and slice

The void in aimless flightThus I return to the source.

–Gesshu Soko (1696).

Frost on a summer day:

all I leave behind is water

that has washed my brush.–Shutei

Bitter winds of winter

but later, river willow,

open up your buds.-Senryu (1790)

Not even for a moment

do things stand still-witness

color in the trees.–Seiju

Farewell-

I pass as all things do

dew on the grass.–Banzan

Holding back the night

with it’s increasing brilliance

the summer moon.–Yoshitoshi.

On a journey, ill;

my dream goes wandering

over withered fields.-Basho.

References

Hawkins, A. (2002). Four Japanese Death Haiku. Academic Medicine 77[1].

Hiroshi, K. (1944). Death Poem. https://en.m.wikipedia.org/wiki/File:Death_poem_by_Kuroki_Hiroshi.jpg

Hoffmann, Y. (1986). Japanese Death Poems: Written by Zen Monks and Haiku Poets on the Verge of Death. Boston, MA: Tuttle Publishing.

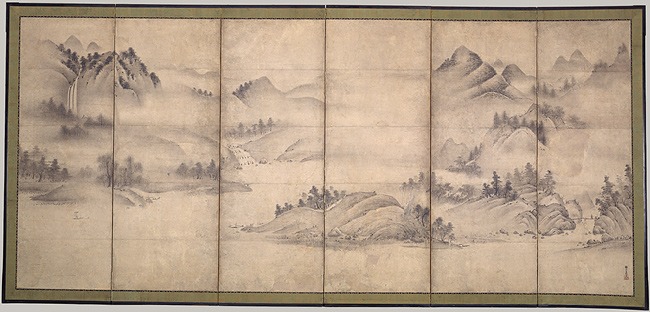

Shinso, K. (1525). Landscape of the Four Seasons. http://www.metmuseum.org/toah/works-of-art/41.59.1,2

Source: Japan Powered