by Sigal Samuel: Black activism and Buddhist mindfulness share a fascinating history — and future…

Valerie Brown is positioned at the intersection of two traditions that can be very helpful to us all right now. She’s a Black woman who’s involved in racial justice work, and she’s a Buddhist teacher who shows people how to use mindfulness to navigate life’s challenges — challenges like, say, a pandemic, a huge economic collapse, racial injustice, and social unrest.

For 20 years, Brown had a high-powered career as a lawyer and lobbyist. Then she radically shifted the focus of her attention to Buddhism. She learned at the feet of the Vietnamese Zen master Thich Nhat Hanh and was ordained as a mindfulness teacher.

I recently spoke with Brown for Future Perfect’s new limited-series podcast, The Way Through, which is all about mining the world’s rich philosophical and spiritual traditions for guidance that can help us through these challenging times.

We talked about the fascinating historical connections between Buddhist practice and Black activism. She explained how we can use mindfulness not just to soothe us as individuals, but also to tackle broader racial inequality today. And she shared some classic Buddhist mindfulness training, which she recently helped rewrite through a racial justice lens.

We know the coronavirus pandemic is disproportionately taking Black lives, and for Brown, that’s deeply personal: Her brother died of presumed Covid-19 just a few months ago.

You can hear our entire conversation in the podcast here. A transcript of our conversation, edited for length and clarity, follows.

Sigal Samuel

Valerie, tell me a bit about yourself and how you became interested in Buddhist meditation. You didn’t grow up with it, right?

Valerie Brown

I grew up in the People’s Republic of Brooklyn. And I grew up with a lot of poverty. My mother was a maid in the Hotel Manhattan and my dad was a tailor in the Bowery. We grew up on public assistance. Early on, there was quite a bit of violence. My dad left. And then when I was 16, my mother passed away. I became an independent student at 18, meaning I had no parental supervision and no parental support.

But I got really lucky. I got a job at Burger King. So I worked, went to City University, and made my way out, running to undergraduate school and graduate school and the big, important job as a lobbyist and lawyer.

In 1995, I attended a public talk given by Zen master Thich Nhat Hanh. The talk was at the Riverside Church, down the street from my brother’s apartment, so I just walked down. And everything that Thich Nhat Hanh was saying was the opposite of how I was living my life. I was this very type A, aggressive, bunker-mentality, hard-as-nails person, just running from tremendous internalized oppression and internalized racism. And I walked out of the talk thinking: That guy! Who is that guy? That day touched something, a spark in me. And I started to practice meditation.

Sigal Samuel

So once you got interested in Buddhism, you began going on retreats and training as a meditator and then as a meditation teacher. What was the experience like for you?

Valerie Brown

Over time, I gradually began to change. I started practicing this particular meditation called metta, or loving-kindness, where you hold a sense of friendship for yourself and then for the people you like. And then for the people you actually don’t know. And then for people maybe you’re not so cool with, maybe even people you hate. And then for everybody, all beings everywhere.

So I started practicing this and I decided, Okay, let me actually practice this at work when I’m in the halls of Congress. Now, I’m a Black woman, with dark skin, with dreadlocks, talking to a very conservative person who may be white from quite a racially segregated area. What I would do when I’m in that conversation with such a person — who, on one level, my mind perceives to be the opposite of me — is, I turn to my breathing. And I would just notice how I’m breathing and feel my feet on the floor and I’d say these words to myself: Soften. Soften. Soften.

My whole body would start softening. And then what I noticed is that instead of trying to persuade the other person — because this is the job of the lobbyist, to be persuasive — I would switch that. I would take sincere and genuine interest in understanding that other person first. Even if I believed that that person was way far out on the opposite end of how I feel. I would ask the person: Tell me more. Help me understand. How are you doing, really? I wouldn’t open my mouth until it could come out sincere.

And what happened then was that other person softened up. The dynamic between us became relational rather than adversarial. That was a form of mindfulness that was interpersonal. That was being peace, conveying peace.

Sigal Samuel

These days you do a lot of racial justice work. And a lot of people might think Black activism and Buddhist mindfulness are two completely separate traditions that have nothing to do with one another. But actually, there was a very special friendship between two of their leaders: your teacher Thich Nhat Hanh and Reverend Dr. Martin Luther King. In the 1960s, they had a blossoming friendship that also had political ramifications. Can you tell me a bit about that relationship?

Valerie Brown

Dr. King and Thich Nhat Hanh shared a real passion for nonviolent, peaceful liberation of all people. One of the most beautiful things I’ve been reading about Dr. King and the great civil rights leaders of the 1963 Birmingham movement is that they said they were acting for the benefit of all people — even the police who set the dogs on them, who abused them.

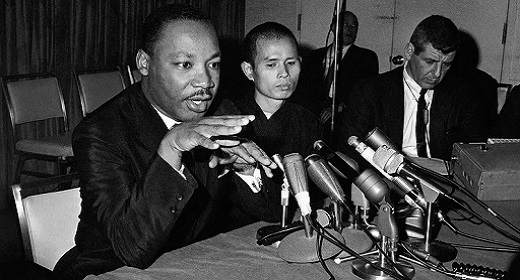

Thich Nhat Hanh and Dr. King met at a press conference in 1966. They were united by the civil rights movement and their struggles for liberation. In 1967, Dr. King nominated Thich Nhat Hanh for the Nobel Peace Prize. They met again [that year] at a conference in Geneva.

And then there’s a lovely story. Dr. King was at a hotel. They were set to meet, but Thich Nhat Hanh was late for the appointment. Dr. King had a plate of food for him. And he kept it warm.

Thich Nhat Hanh has written about that very tiny moment, which may seem insignificant, but you can just sense the personhood in the connection of the two people, heart to heart. Here you have these great leaders who could not only attend to these massive political movements of their time, but could also focus on the very moment, the very humanness of care for another person.

Sigal Samuel

It does sound like they connected on a really human intimate level. And I know that this originally started because Thich Nhat Hanh wrote a letter to Dr. King in 1965, asking him to please help advocate for ending the Vietnam War.

And Dr. King was getting a lot of pushback from people around him saying not to get involved in this because he was already dealing with a lot and this wasn’t his business. And Dr. King said, “For those who are telling me to keep my mouth shut, I can’t do that. I’m against segregation at lunch counters, and I’m not going to segregate my moral concerns.”

He decided to get involved in advocating against the Vietnam War. And so there was actually this very political dimension to this spiritual friendship between these two leaders. I think that’s interesting to note, because people sometimes think about Buddhism as quite disconnected from politics. But Thich Nhat Han was anything but.

Valerie Brown

Thich Nhat Han coined the term “engaged Buddhism.” This goes back to the Vietnam War. As a young monastic with other monks and nuns in Vietnam, there were choices. They could have stayed in the monastery and prayed. Or they could have taken themselves out of the monastery and engaged with the suffering of the people in the streets.

In the case of Thich Nhat Hanh and many of the people at that time, they made a conscious decision which cost them dearly — their lives, their own affiliation with the political people in Vietnam. Thich Nhat Hanh was isolated [and exiled]. He was not able to return to Vietnam for decades because of his outspoken activism. So we have in this extraordinary human being the footprint of how to engage in nonviolent, peaceful action for the benefit of all beings.

Sigal Samuel

Let’s fast forward to today. We’re now facing a global pandemic, and we know it’s disproportionately taking Black lives. At the same time, we’re seeing this massive upswell of support for Black lives. Given what you’ve said about engaged Buddhism, how do you think Buddhist teachings and racial justice work can support each other right now?

Valerie Brown

What I would say is Black justice is justice for all people. Thich Nhat Hanh has coined the term “interbeing.” Interbeing, meaning that we are interconnected. When a Black person is able to obtain justice and peace, all people are going to benefit. And so it’s an illusion to think that somehow the white suburban person in the Midwest is separate from that Black transgender woman in Brooklyn, New York. That would be a mistake. We are connected. What happens in Wuhan, China, affects people in San Francisco.

Sigal Samuel

Yes, I think the pandemic has really proven this interbeing concept to be true. I don’t just mean in some abstract spiritual sense, but in a very scientific, epidemiological sense.

Interbeing comes up in a new version of the Five Mindfulness Trainings that you recently co-authored. These are words that are often recited in Buddhist circles, and they’re designed to make us more mindful of things like our consumption. But your version reframes all those trainings through the lens of racial justice. Can you give me a little snippet of the trainings that feels meaningful to you?

Valerie Brown

Here’s a little part. This is the third contemplation.

“I am committed to looking tenderly at my suffering, knowing that I am not separate from others, and that the seeds of suffering contain the seeds of joy. I am not afraid of bold love that fosters justice and belonging. And tender love that seeks peace and connection. I cherish myself and my suffering without discrimination. I cherish this body and mind as an act of healing for myself and for others. I cherish this breath. I cherish this moment. I cherish the liberation of all beings.”

Sigal Samuel

Beautiful. Thank you. You mentioned this idea that without suffering you can’t have joy, that suffering contains the seeds of joy. And I know that is something Thich Nhat Hanh says often. He says the phrase, “No mud, no lotus.” If you don’t have the mud, you can’t have the beautiful flower that grows out of it.

But I want to talk about this in the context of the pandemic and the protests. On both the Covid-19 front and the racism front, which are interconnected, there is so much suffering. Honestly, how do you find seeds of joy in that?

Valerie Brown

The best way I can explain this is through my brother Trevor. Trevor died on February 21 in New York City. He was on the ventilator and probably on the beginning wave of Covid-19. I had a lot of suffering to see him die. It was very difficult for me. But one of the things that I realized in his online memorial is that the reason that I was grieving so much and felt so sad was because the love was so deep.

If he wasn’t meaningful for me, if I didn’t have that love, if it wasn’t valuable, I probably wouldn’t be suffering. But it was. I lost something valuable, something meaningful.

And so we’re fighting, peacefully, nonviolently, for something that is very important. And that is freedom and liberation and justice for a world that everyone can belong to. That’s a good thing.

Sigal Samuel

First of all, I’m really sorry to hear about your brother. And it’s amazing to me that you are able to, just a few months later, realize that the seed of beauty in this is that if there wasn’t such preciousness here, you wouldn’t have felt such grief.

You also just mentioned that you’re fighting nonviolently for this cause that is really important and hopeful. I want to pick up on that thread of nonviolence.

Dr. King said, “Never succumb to the temptation of becoming bitter. As you press for justice, be sure to move with dignity and discipline, using only the instruments of love.”

I don’t know about you, but as a queer woman of color, I find it hard to do that sometimes. Can you talk a bit more about how we can keep feelings of bitterness and anger from overwhelming us when we see injustice? And I’m also wondering, maybe sometimes anger isn’t a bad thing? Maybe it can sometimes be a useful, galvanizing force to push us to fight for justice?

Valerie Brown

It’s an important question. Anger can feel quite impulsive and fiery and seductive. It can feed the energy of violence.

And so the first thing I’d say is that in the sutras, the Buddha refers to the mind as like a storehouse of seeds. So there’s a seed of anger. A seed of fear. A seed of hope. And depending upon our thoughts or words or actions, these seeds get activated. You get cut off in traffic? Boom. The seed of anger gets watered or activated. You have a lovely conversation with a dear friend? The seed of gratitude gets nourished.

Part of taking good care of emotion, of hate in particular, is, number one, to recognize when it’s activated. Can’t do much if you’re unaware.

After that recognition is to calm ourselves through what we have that’s a constant. That’s our own breathing. With time and with practice, we can use the breath to calm ourselves down. Not suppressing, not denying, not calling it disappointment when it’s actually rage. To be very clear, this is rage. And then breathing with that. Taking very good care of that energy.

What I’ve come to understand is that that bitterness is a constriction in the heart. It actually makes me smaller. And so the invitation is to play in a bigger space. And the bigger space is love, is compassion. We are called into that bigger space. And we’re up for it.

Sigal Samuel

I’ve got to be honest. For me, to move from rage to love, that’s a tall order. But what you’re saying reminds me of this old Buddhist sutra, the Discourse on the Five Ways of Putting an End to Anger. One thing it says in that sutra is if someone is being unkind they’re probably suffering a lot. Maybe if I can remember that, it could help spark a bit of compassion in me for that person and maybe help me move the needle a bit from rage to love.

Another thing that sutra says is that the way we choose to direct our attention is crucial. If someone is acting with unkind words or unkind behaviors, we can choose to focus our attention on what they’re doing that’s unkind. But the sutra says to try to actually redirect your attention to what in this person is kind, is good.

Valerie Brown

It reminds me of a calligraphy that Thich Nhat Hanh has that says, “Are you sure?” I can walk around with very fixed ideas, very attached to my own views. And so one of my deepest spiritual practices is to ask myself, Am I sure? What are my perceptions, assumptions, beliefs, and what is the lineage of all that? Where did that come from? How am I attached to it?

That kind of loosens things up. That mindset — I’ve got this idea, maybe I’m right, maybe I’m not right — that allows for whatever the suffering is, whatever the aversion is, to have some flexibility.

Sigal Samuel

In addition to this phrase, “Are you sure?”, one of the phrases I hear most often in the Buddhist context is this concept of taking refuge. I want to talk about refuge in the current moment, where we’re all dealing with a lot of stress and suffering.

If all one is after is a temporary refuge from suffering, there is a term for that trap: spiritual materialism, where you’re just getting into meditation because you want some temporary material benefit or attainment. I wonder if you could tell us what you think is a better way to understand taking refuge. How can we use these practices in a way that’s not selfish but is engaged with the broader ethical and political issues we’re all seeing right now?

Valerie Brown

Taking refuge is really important, especially at this time when there’s so much upheaval. And that may feel like a really grand thing to say, to “take refuge.” But that can be as simple as taking refuge in this moment. Recognizing that I can breathe, I am alive, I can make a difference, I can contribute. That’s taking refuge. That’s not a small thing. There’s countless people who cannot do that.

The other thing I would say to the spiritual materialism point is that one of the foundations of mindfulness is ethics. There is an ethical component of it.

Often, in the United States, you see mindfulness sold in these packages that are all about focus, attention. It’s so that I can do more, so I can get the promotion, so I can buy the car or whatever. Right? I even hear, as I say this, a kind of cynicism in myself. And I want to even question that, my own belief around that. But I would say that I’ve seen a lot of that materialism myself. It’s sad because there is such a critical component of mindfulness that is about the prosocial good. We’re not only generating happiness within ourselves. We want to share that with other people.

We are quite good, particularly as Americans, at pursuing materialism, pursuing happiness. Not so good at generating it within ourselves and sharing that with other people. And so the basis for the whole practice is about creating a more peaceful society, a more compassionate society. This is something that we really cannot lose sight of.