by (Ben Greenfields Fitness): I suppose my desire to explore prayer and focus more on tapping into the power of prayer in my own life was partially sparked when I was writing this article a few months back about union with God…

In that article, I included the following anecdotes:

“…magically, this same all-powerful God continues to walk among us mere humans. And we can actually talk to him. To me, this concept is simultaneously breathtaking and humbling. Don’t take for granted the ability to be in daily union with the mightiest King that has ever existed—to walk with Him, talk with Him, and share his joy…

…I have three simple suggestions for you to maintain your union with God.

First, take everything to God in prayer. He will grant you wisdom and discernment if you ask for it. He will give you answers. All you need do is ask. This week, every day, even with the smallest of decisions, consider coming to God with questions such as “What should I eat?,” “Who should I ask about this problem?,” “What task should I tackle first?”. Then simply stop, breathe, and listen for the still, small voice in the silence. He will give you direction.

Second, stop at a few points during your busy day, once again breathe, and simply survey the wonders of Creation around you and speak to God a simple phrase: “I am here. Speak to me and show me what You want to teach me.” Then, once again, be silent and listen. God’s words to you will once again come in the still, small silence.

Finally, be grateful and stop to thank God multiple times during the day. In my article on breathwork, I told you:

“…each night, as I fall asleep to the gentle diaphragmatic lull of my own “4-count-in-8-count-out” breathwork pattern, I’m silently thanking God and trusting God that there will be yet more oxygen available for me for my next inhale. Indeed, the mere act of mindful breathing combined with a silent gratefulness to God for each and every breath is a wonderful practice, and one I recommend you try the next time you’re stuck in twenty minutes of traffic. After all, our great Creator smiles when we worship Him, and I certainly think that no king would complain of a subject entering their throne room for several minutes and saying with the deepest gratitude with each breath…”Thank you…thank you…thank you…”

But don’t just thank Him with your breath. Thank Him before a meal. Thank Him when you see a bald eagle soaring overhead. Thank Him when you’re stuck in traffic. Thank Him when you get a good e-mail. Thank him when you get a bad e-mail. Thank Him when a loved one hugs you. Thank Him in all things.”

Since writing that article, and discovering the deep meaning and fulfillment I’ve derived from the daily Scripture reading practice outlined here while continuing to focus on building my union with God, I’ve continued to study prayer, pondering such questions as…

…How can I practically implement prayer into my life more often, without it seeming like a formal, dry, or intellectual affair, which it often seems to be for me?

…What happens to my psychology and mood when I pray?

…How did great leaders and inspirational figures from history pray?

Over the past several weeks, I think I’ve found some pretty good answers to these questions, and so, I want to share those answers about prayer with you in today’s article.

The Power Of Prayer

Before delving into the practical aspects of how we can and should pray, it’s important to understand how powerful prayer really can be. In his thought-provoking book, The Way of the Heart: Connecting with God Through Prayer, Wisdom, and Silence, Henri J.M. Nouven writes:

“Prayer is standing in the presence of God with the mind in the heart; that is, at that point of our being where there are no divisions or distinctions and where we are totally one. There God’s Spirit dwells and there the great encounter takes place. There heart speaks to heart, because there we stand before the face of the Lord, all-seeing, with us.”

Thomas Merton, a twentieth-century American Trappist monk and social activist, was known as a great thinker, philosopher, and a devout man of God. One of Merton’s most notable accomplishments was sharing his views of the transformative experience of what he described as a “mystical union with God.” Merton considered prayer to be the most worthy of all activities in which a human can engage, with rewards that are twofold: contact with God, and the attainment of the most elevated expression and highest actualization of one’s own self.

I fully agree with Nouven and Merton. There is something very special that happens during prayer—something that goes beyond reading Scripture, meditating, journaling, singing, or any of the other important spiritual disciplines I discuss here.

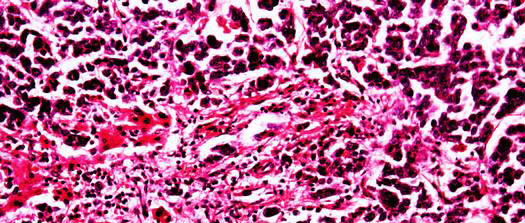

Perhaps part of the power of prayer is related to what actually occurs on a biological level when we pray. In the book Miracles Every Day: The Story of One Physician’s Inspiring Faith and the Healing Power of Prayer you can read about a new field of science and faith study called “neurotheology,” which blends the existing fields of biology, neurology, psychology, and theology.

At the University of Pennsylvania, Andrew Newberg, M.D. directs the Center for Spirituality and the Mind, where he has conducted studies of people who meditate or pray for long periods every day over the course of numerous years. Dr. Newberg’s research has demonstrated impressive changes as a direct response to prayer in brain structures at the neuronal level. Furthermore, he has found that the longer and more frequently one is engaged in meditation or prayer, the more extensive the changes are in these brain structures.

Specifically, his brain-scan studies have shown that prayer powerfully stimulates the anterior cingulate, the center of the nervous system in which the balance between thought and feeling is sustained. Prayer seems to “exercise” the anterior cingulate by stimulating, strengthening, and enlarging it—while simultaneously decreasing neuronal activity in the limbic system, where emotions such as fear, shame, and anger are processed. Scientists have actually correlated this type of highly stimulated anterior cingulate with a unique kind of personality characterized by enhanced cognitive function and focus, along with increased stress resilience and a heightened ability to be able to withstand and handle physically, mentally, and emotionally difficult scenarios.

The great Thomas Merton, who I mentioned above, described in many of his writings moments of transcendence that he experienced during intense prayer, often characterized by feelings of selflessness and timelessness. Brain-scan studies have demonstrated at a structural level that this actually occurs because, during prayer, activity in the parietal lobe decreases, and one of the results of the decrease in activity in the parietal lobe is—you guessed it—an augmented perception of timelessness and spacelessness, very similar to what one might experience from the use of plant medicine or psychedelics.

These insights from neurotheological studies lend scientific credence and a physiological basis to what prophets, philosophers, and religious advocates have believed for millennia: Prayer seems to, nearly magically, change your life for the better. This appears to partially be because the brain becomes less prone to feeling anger, anxiety, aggression, and fear while simultaneously increasing tendencies towards empathy, compassion, and love. This reminds me a bit of the fascinating biological impact of a daily gratitude practice, which I describe here and here.

Perhaps this is why many notable religious figures of history who have all who have walked closely with God have also viewed prayer as an integral component in their lives. Many of these figures are described in Richard Foster’s book Prayer, including:

- Jesus: Jesus frequently slipped away to remote or quiet places to pray and meditate in solitude. In the gospel of Mark we are told, “And in the morning, a great while before day, he rose and went out to a lonely place, and there he prayed” (Mark 1:35).

- David: In Psalms 63:1, King David says, “Early will I seek Thee,” highlighting the importance of morning prayer, in addition to his vast collection of written prayers throughout the book of Psalms.

- The apostles: Although I’m sure the apostles were tempted to invest their energy in many important and necessary tasks, they still gave themselves continually to prayer and the ministry of the word, “But we will give ourselves continually to prayer, and to the ministry of the word.” (Acts 6:4).

- Martin Luther, German professor of theology, priest, author, composer, Augustinian monk, and seminal figure in the Reformation declared, “I have so much business I cannot get on without spending three hours in prayer.” He held as a spiritual axiom that “He that has prayed well has studied well.”

- English cleric, theologian, and evangelist John Wesley said, “God does nothing but in answer to prayer.” He backed up this conviction by devoting two hours daily to a sacred exercise of prayer.

- One quite notable feature of David Brainerd, American missionary to the Native Americans was his praying. His personal journal is chock-full of accounts of prayer, fasting, and meditation, such as “I love to be alone in my cottage, where I can spend much time in prayer.” and “I set apart this day for secret fasting and prayer to God.”

For these pioneers in the frontiers of faith, prayer was not just a small habit tacked onto the periphery of their lives—rather it was their lives. The following powerful anecdote from Christian evangelist George Muller’s Meditating on God’s Word is, in my opinion, a wonderful example of what can happen when we do not just read the Bible, but also meditate upon it (as you learned in this article) and, most importantly, pray:

“While I was staying at Nailsworth, it pleased the Lord to teach me a truth, irrespective of human instrumentality, as far as I know, the benefit of which I have not lost, though now…more than forty years have since passed away. The point is this: I saw more clearly than ever, that the first great and primary business to which I ought to attend every day was, to have my soul happy in the Lord. The first thing to be concerned about was not, how much I might serve the Lord, how I might glorify the Lord; but how I might get my soul into a happy state, and how my inner man might be nourished. For I might seek to set the truth before the unconverted, I might seek to benefit believers, I might seek to relieve the distressed, I might in other ways seek to behave myself as it becomes a child of God in this world; and yet, not being happy in the Lord, and not being nourished and strengthened in my inner man day by day, all this might not be attended to in a right spirit. Before this time my practice had been, at least for ten years previously, as an habitual thing, to give myself to prayer, after having dressed in the morning.

Now I saw, that the most important thing I had to do was to give myself to the reading of the Word of God and to meditation on it, that thus my heart might be comforted, encouraged, warned, reproved, instructed; and that thus, whilst meditating, my heart might be brought into experiential communion with the Lord. I began therefore, to meditate on the New Testament, from the beginning, early in the morning. The first thing I did, after having asked in a few words the Lord’s blessing upon His precious Word, was to begin to meditate on the Word of God; searching, as it were, into every verse, to get blessing out of it; not for the sake of the public ministry of the Word; not for the sake or preaching on what I had meditated upon; but for the sake of obtaining food for my own soul. The result I have found to be almost invariably this, that after a very few minutes my soul has been led to confession, or to thanksgiving, or to intercession, or to supplication; so that though I did not, as it were, give myself to prayer, but to meditation, yet it turned almost immediately more or less into prayer. When thus I have been for awhile making confession, or intercession, or supplication, or have given thanks, I go on to the next words or verse, turning all, as I go on, into prayer for myself or others, as the Word may lead to it; but still continually keeping before me, that food for my own soul is the object of my meditation.

The result of this is, that there is always a good deal of confession, thanksgiving, supplication, or intercession mingled with my meditation, and that my inner man almost invariably is even sensibly nourished and strengthened and that by breakfast time, with rare exceptions, I am in a peaceful if not happy state of heart. Thus also the Lord is pleased to communicate unto me that which, very soon after, I have found to become food for other believers, though it was not for the sake of the public ministry of the Word that I gave myself to meditation, but for the profit of my own inner man. The difference between my former practice and my present one is this. Formerly, when I rose, I began to pray as soon as possible, and generally spent all my time till breakfast in prayer, or almost all the time. At all events I almost invariably began with prayer…. But what was the result? I often spent a quarter of an hour, or half an hour, or even an hour on my knees, before being conscious to myself of having derived comfort, encouragement, humbling of soul, etc.; and often after having suffered much from wandering of mind for the first ten minutes, or a quarter of an hour, or even half an hour, I only then began really to pray. I scarcely ever suffer now in this way.

For my heart being nourished by the truth, being brought into experiential fellowship with God, I speak to my Father, and to my Friend (vile though I am, and unworthy of it!) about the things that He has brought before me in His precious Word. It often now astonished me that I did not sooner see this. In no book did I ever read about it. No public ministry ever brought the matter before me. No private intercourse with a brother stirred me up to this matter. And yet now, since God has taught me this point, it is as plain to me as anything, that the first thing the child of God has to do morning by morning is to obtain food for his inner man. As the outward man is not fit for work for any length of time, except we take food, and as this is one of the first things we do in the morning, so it should be with the inner man. We should take food for that, as every one must allow. Now what is the food for the inner man: not prayer, but the Word of God: and here again not the simple reading of the Word of God, so that it only passes through our minds, just as water runs through a pipe, but considering what we read, pondering over it, and applying it to our hearts…. I dwell so particularly on this point because of the immense spiritual profit and refreshment I am conscious of having derived from it myself, and I affectionately and solemnly beseech all my fellow believers to ponder this matter.

By the blessing of God I ascribe to this mode the help and strength which I have had from God to pass in peace through deeper trials in various ways than I had ever had before; and after having now above forty years tried this way, I can most fully, in the fear of God, commend it. How different when the soul is refreshed and made happy early in the morning, from what is when, without spiritual preparation, the service, the trials and the temptations of the day come upon one!”

Christians are repeatedly encouraged by Jesus to pray. He tells us in the Gospel of Luke, “How much more will the heavenly Father give the Holy Spirit to those who ask him (Luke 11:13).” We are to pray so that God can help us to become more like Him in our own spiritual growth. We are to pray for the renewal and the growth of our soul. We are to pray to give thanks to God for all His blessings and provisions. We are to pray to seek forgiveness for our sins. We are to pray to seek help for others as well as ourselves.

Most importantly, we are to pray without ceasing. Here are several of the Scripture references to this concept of constant, incessant prayer:

- 1 Thessalonians 5:17: “Pray without ceasing.”

- Ephesians 6:18: “Pray in the Spirit at all times and on every occasion.”

- Matthew 6:5-7: “And when you pray, do not be like the hypocrites, for they love to pray standing in the synagogues and on the street corners to be seen by others. Truly I tell you, they have received their reward in full. But when you pray, go into your room, close the door and pray to your Father, who is unseen. Then your Father, who sees what is done in secret, will reward you. And when you pray, do not keep on babbling like pagans, for they think they will be heard because of their many words.

- Luke 11:9: “So I say to you: Ask and it will be given to you; seek and you will find; knock and the door will be opened to you.”

- Luke 18:1: “Then Jesus told his disciples a parable to show them that they should always pray and not give up.”

- Colossians 4:2: “Devote yourselves to prayer, being watchful and thankful.”

In other words, our life should ideally be one of constant prayer in which we are continually in union and relationship with God, drawing near to Him from morning to evening. Saint Isaac of Syria, a 7th-century Church of the East Syriac Christian bishop summed it up quite well when he said that “…it is impossible to draw near to God by any means other than unceasing prayer.”

The Problem With Prayer

However, I don’t know about you, but the prospect of praying all the time seems daunting.

After all, when I was growing up in a Christian church, prayer was usually positioned as a formal activity with a specific structure that required carving out time and forethought to wax poetic to the Creator. Not that there’s anything wrong with that approach to prayer per se, but I think that when you consider prayer in that way only, it becomes something very much like the same type of formidable, intimidating activity that keeps many people from regular meditation: feeling as though they need to do it in some kind of perfectly systematized way, X number of times per day for Y minute sitting in Z position—which, as anyone who has taken a few simple and calming mindful breaths while stuck in traffic knows is not necessarily the case. Because of this conundrum, it can be easy to verbally attest to the importance of prayer as foundational to a Godly life, but based on our oft-faulty assumptions about how it should be conducted, prayer often gets crowded out as the calendar fills up with other duties or we simply become too mentally drained or fatigued during the day to conduct a “formal prayer session.”

Sure, dedicated time to formal, traditional prayer (or meditation)—in which one goes off to a quiet place, kneels or adopts any other prayerful position, and speaks to God for a significant period of time—is certainly laudable and appropriate, but there can be other ways to pray that allow you to “pray without ceasing” without giving up your job, family time, hobbies, and other activities to move to a pristine Himalayan mountaintop so that you can be a constant and unceasing prayer warrior.

I suppose the best way to describe this problem with trying to pray without ceasing is that we tend to over-intellectualize prayer. As opposed to the simple prayer of early Christian hermits, ascetics, and monks such as the Desert Fathers and Mothers of the early church, intellectualized prayer is the common form of prayer encountered and encouraged in most mainstream churches, paired hand-in-hand with didactic and intellectual sermons, argumentative apologetics, and a focus on “prim-n-proper theology” that can stand in stark contrast to a more charismatic and aesthetic approach to speaking with and worshiping God.

For example, I was always taught that I, similar to the Lord’s Prayer, should have a distinct prayer structure in which one opens with worship, thanksgiving and gratitude, then on to petitions, then on forgiveness and repentance, and finally, some kind of official prayer closure. The best way I can describe the feeling I sometimes have with this type of prayer is that it sometimes seems to keep me more in a mindset of praying “in the head” than praying “from the heart.”

As I tell my children, it is one thing to know about God, but an entirely different thing to truly know God. The former is more mental, and the latter is more spiritual. Ideally, one has a grasp, understanding, and practice of both. Similarly, it is one thing to pray intellectually, and quite another to pray in a ripped-open, raw, and emotional manner.

Because of this mental, cognitive approach to prayer that is all-too-common for many people, prayer can often feel as though one is talking to God or talking at God in a lonely one-sided monologue rather than a dialogue…

“…thank you for this…”

“…please give me that…”

“…forgive me for this and that…”

“…whatever your will is in my life…”

“…amen.”

In The Way of the Heart: Connecting with God Through Prayer, Wisdom, and Silence Henri J.M. Nouwen alludes to this over-intellectualization of prayer when he says:

“For many of us prayer means nothing more than speaking with God. And since it usually seems to be a quite one-sided affair, prayer simply means talking to God. This idea is enough to create great frustrations. If I present a problem, I expect a solution; if I formulate a question, I expect an answer; if I ask for guidance, I expect a response. And when it seems, increasingly, that I am talking into the dark, it is not so strange that I soon begin to suspect that my dialogue with God is in fact a monologue. Then I may begin to ask myself: To whom am I really speaking, God or myself?”

If you think of prayer as simply speaking at God or jumping through a set of structured hoops, then it may not be long before you abandon prayer altogether, primarily because it can feel so intellectual and one-sided.

In contrast, the phrase “pray without ceasing” that the apostle Paul uses in his letter to the church in Thessalonians literally translates “come to rest.” The Greek word for “rest” is hesychia and this kind of hesychastic prayer is associated with a style of prayer now called “contemplative prayer,” which is very similar to the ancient form of Christian meditation practiced by the Desert Fathers and Mothers of the early church I alluded to above. Contemplative prayer is simply defined as a wordless, trusting opening of self to the divine presence—essentially moving from a “conversation” with God to “communion” with God.

This type of conversation with God abandons a formulaic approach to prayer. Instead, the main themes that characterize a contemplative prayer from the heart are that it tends to be short and sweet, unceasing, and an all-encompassing trusting and opening prayer that descends from the regions of the mind into the regions of the heart. Nouwen defines this descent like this:

“When we say to people, ‘I will pray for you,’ we make a very important commitment. The sad thing is that this remark often remains nothing but a well-meant expression of concern. But when we learn to descend with our mind into our heart, then all those who have become part of our lives are led into the healing presence of God and touched by him in the center of our being. We are speaking here about a mystery for which words are inadequate. It is the mystery that the heart, which is the center of our being, is transformed by God into his own heart, a heart large enough to embrace the entire universe. Through prayer we can carry in our heart all human pain and sorrow, all conflicts and agonies, all torture and war, all hunger, loneliness, and misery, not because of some great psychological or emotional capacity, but because God’s heart has become one with ours.”

Contemplative prayer often focuses on one word or a simple phrase that is repeated throughout the prayer, or simply at various intervals throughout the day, in a form of near childlike repetition, such as:

“Jesus Christ, have mercy on me…”

or

“Oh God, thank you…”

or

“Lord, I’m so grateful…”

or

“I am here, God…”

I’ve personally found that a humble repetition of a single word or phrase helps “bring my mind into my heart” more significantly than a lengthy extemporaneous and theologically astute prayer and allows me to, throughout the day, pray without ceasing—without feeling intimidated or overwhelmed by the need to wax fancy or lengthy in my personal prayers. In addition, although I do have a prayer list that I keep for many people I have promised I’ll pray for, or people God has placed upon my heart to pray for, I’ll often simply draw an image of that person in my mind, or just say that person’s name, and trust that God knows exactly what that person needs in the moment. This isn’t done out of laziness or haste, but rather out of a desire to be able to simply feel God’s presence and speak to God openly throughout the day.

Finally, this type of contemplative prayer lends itself well to meditation and breathwork as well, as I can simply sit still, breathe deeply, allow my heart to fully open, then repeat a name of God, such as “Abba” or “Creator” over and over again, or an attribute of God, such as “love” or “mercy” over and over again.

Do you see what I’m saying here?

It’s basically this: Don’t feel as though every time you speak with God it must be a formal, intellectual, theological, and perfectly structured prayer. Don’t get me wrong: this type of “complex” prayer is something that I think should be a part of one’s prayer life, but doesn’t need to be the sole means via which one prays. Instead, prayer can also be a simple acknowledgement of God’s presence or a very basic mantra or series of mantras that you repeat at various points throughout the day. For me personally, this has allowed a consistent and achievable ability to be able to truly “pray without ceasing.”

But there are other prayer tips and techniques I’ve discovered along my journey too, and so now I’ll share the most helpful ones with you below.

How To Pray

Below are five ways that I’ve found effective for weaving prayer into my daily routine. As you read through these ways to pray, you may find that some particularly resonate with you, and I hope you find them helpful for enabling yourself to pray without ceasing, from the heart.

1. Memorize Certain Prayers That You Can Recite Throughout The Day

Having prayers that you have memorized or written down to recite throughout the day can be one effective way to pray without ceasing. For example, I recently visited my father Gary Greenfield and spent the weekend with him. He practices Orthodox Christianity and has multiple prayer books full of prayers that he has memorized and recites or reads at various points throughout the day.

One such prayer is known as “the Jesus Prayer,” which is a short formulaic prayer esteemed and advocated especially within the Eastern Orthodox churches. It goes like this:

“Lord Jesus Christ, Son of God, have mercy on me, a sinner.” It is often repeated continually as a part of personal ascetic practice and considered to be part of the hesychastic approach to prayer I mentioned earlier in this article. Often these types of short and simple memorized or ritualistic prayers are structured throughout the day. Below is an example of such an approach (more details here):

- Time: 6:30am and 11:00pm for 20 minutes each time

- Begin by lighting a candle, and making three prostrations and then stand quietly to collect yourself in your heart

- Trisagion Prayer

- One of six Morning or Evening Psalms

- Intercessions for the living and the dead

- Psalm 51 and confession of our sinfulness

- Doxology and the morning or evening prayer

- Personal dialogue with God

- Jesus prayer – repeat 100 times.

- Reflect quietly on the tasks of the day and prepare yourself for the difficulties you might face asking God to help you .

- Dismissal prayer

- Stop mid-morning, noon, and mid-afternoon to say a simple prayer.

- Repeat the Jesus Prayer in your mind whenever you can throughout the day.

- Offer a prayer before and after each meal thanking God and asking for His blessing.

I fully realize that you may have raised an eyebrow at some of the elements above, such as repeating the Jesus Prayer 100 times, and while I fully agree that adherence to this type of rigid, repetitive, or timed prayer structure may not be attainable for many, there are other elements of this schedule that make sense, such as stopping mid-morning, noon, and mid-afternoon to say a simple prayer, or repeating the Jesus prayer in your mind whenever you can throughout the day.

Here’s another example: I personally have a memorized prayer that I recite each morning when I jump into my cold pool and swim back and forth. Because the prayer is woven into something I’m already doing anyways each day as part of my routine, it’s something that I very seldomly skip, and I’ve found this approach to actually allow me to systematize the process of speaking to God each morning:

“Our Father in heaven, I surrender all to you

Turn me into the father and husband you would have for me to be

Into a man who will fulfill your great commission

And remove from me all judgment of others

Grant me your heavenly wisdom

Remove from me my worldly temptations

Teach me to listen to your still, small voice in the silence

And fill me with your peace, your love, and your joy. Amen.”

Of course, another example of a prayer that you can memorize and recite from your heart throughout the day is the Lord’s Prayer, from Matthew 6:6-13 in the Bible:

“Our Father which art in heaven,

Hallowed be Thy name.

Thy kingdom come.

Thy will be done in earth,

as it is in heaven.

Give us this day our daily bread.

And forgive us our debts,

as we forgive our debtors.

And lead us not into temptation,

but deliver us from evil:

For Thine is the kingdom, and the power,

and the glory, for ever.

Amen.”

2. Keep A Prayer List

In my article about how to read the Bible, I filled you in on an app that my entire family uses called “YouBible”. In addition to offering the convenience of a host of done-for-you Bible reading plans, it also includes a handy prayer list that you can share with anyone else who is your friend or follower on the YouBible app (or you can just keep the prayer list to yourself if you’d like). Since I’m prone to forget people I’ve offered to pray for or specific things I want to pray about it, I find it tremendously helpful to be able to simply open the prayer list on my phone, tablet or computer and have at-a-glance list of anything or anyone that I want to bring before God. Each morning and evening, my family gathers together for our meditation and journaling practice, and as part of that, use the prayer list to remind us what to pray about. I know others who keep a prayer journal by their bedside or even on a scrap of paper tucked away into their Bible.

Some people find that an ever-expanding prayer list like this can be intimidating and lead to similar daunting or time-consuming issues with prayer that I’ve described earlier in this article, but here’s the thing: you don’t have to go through the entire list every time you pray. Often, I’ll spend an entire day in multiple prayer sessions attending to just a few people or items who are on the list. What’s most important is to actually have a written log somewhere of, for example, people who you’ve told you would pray for, along with the details of what you’re praying about for them. Consider this to be built-in accountability for your prayer practice.

3. Pray Regularly With A Spouse Or Loved One

One of the best pieces of marriage advice that I ever received was to pray with my wife each night before bed. Although I’ve slightly adapted that advice to now instead pray with the entire family every night before bed (usually gathered in my twin boys’ room) the concept remains the same as that outlined in Matthew 18:20: “For where two or three gather in my name, there am I with them.” Not only does the power of prayer seem to become even more magnified when someone is there praying with you, muttering “Amen”‘s and “Yes,Lord”‘s and squeezing your shoulder or your hand as you pray, but, similar to a prayer list, having someone with which you regularly pray builds in accountability and encouragement to your practice of prayer.

However, it’s important that there be an understanding between you and whoever it is you’re praying with. It can’t be a loosy-goosy, sometimes-remember/sometimes-don’t morning or evening prayer routine. It needs to be as automatic as brushing your teeth, or pulling on your pajamas or flipping off the lights: whether it’s a family affair or a spousal relationship, there must be a dedicated, identifiable time or times that you all pray together. For the Greenfield family, regular prayer times together as a family come at least three times per day: after morning meditation, before dinner, and before bed. I would encourage you to engage as many of your family members or loved ones as possible to join you in a practice of prayer, and to also, if possible, share the same prayer list.

4. Combine Fasting And Prayer

As I alluded to in this article on temptations, Jesus experienced an extraordinary transformation following his forty-day stint of fasting in a rugged mountain wilderness location near the Jordan River.

It was only after this experience that Jesus returned to Galilee an entirely new man and commenced to perform a host of impressive miracles. It turns out that the combination of prayer and fasting has deep historical roots in Christianity. In the Old Testament, fasting combined with prayer was used when there was a deep need and dependence for God’s work in one’s life or in a particular set of often dire circumstances, such as abject helplessness in the face of actual or anticipated calamity. Prayer and fasting are historically combined for periods of mourning, repentance or deep spiritual need.

For example, Daniel 9:3 says, “So I turned to the Lord God and pleaded with him in prayer and petition, in fasting, and in sackcloth and ashes.” King David prayed and fasted over his sick child in 2 Samuel 12:16, and wept before the Lord in his fasted state in earnest intercession in verses 21 and 22 of that same chapter. In Esther 4:16, Esther urges Mordecai and the Jews to fast for her before she planned to appear before her husband the king. The first chapter of Nehemiah describes Nehemiah combining prayer and fasting because of his deep distress over the distressing news that Jerusalem had been desolated. We are told in Luke 2:37 that the prophetess Anna “never left the temple but worshiped night and day, fasting and praying”.

The probable reason that fasting and prayer can be so powerful is that fasting dramatically sharpens the mind, reduces distractions or sluggishness brought on by calorie consumption, and denies the body in a manner that strengthens the resilience of soul and spirit, often causing prayers to become more deep, thoughtful and meaningful. In the book Atomic Power With God (which I recommend you read as an excellent, classic treatise on how to combine prayer and fasting), author Franklin Hall describes prayer and fasting as follows:

“PRAYER and FASTING move the hand that controls the Universe. When a person shuts out the world for a season of prayer, fasting, and consecration, it opens the heart of God and the windows of heaven and brings the forces of God into action on your behalf. When a person begins to fast and pray, they become a channel for the Holy Ghost to flow through as a yielded vessel. Fasting without much prayer is like having a car with no gas to operate the vehicle. Your set-aside season of fasting should be accompanied by much more prayer than just your normal daily prayer life of one hour a day. After about the third day of your fast, the flesh barrier has basically been broken through and these first few days of crucifying the flesh can feel like you are accomplishing nothing—because most of the time you FEEL nothing. Now, there are those special times when you are able to weep and cry under th power of God during these first few days of fasting, but my experience has been that it’s very rare. Remember … fasting without prayer is only a diet. You MUST find a secret place and spend time with HIM alone while you fast. You need to find a place you can speak things in private and take authority over personal circumstances you are addressing without feeling intimidated or feel like someone else is listening.”

While I don’t necessarily think that to be spiritually fit you must be in a state of constant fasting and prayer, I do encourage you, when there is a particularly problematic, distressing or meaningful thing that you need to pray about, that you consider a day of fasting, and that you take the twenty minutes to an hour that you’d normally spend eating a breakfast, lunch or dinner on that day to instead slip away for a deeper state of meditation and prayer than you would normally otherwise be able to experience.

5. Regularly Ask Others “How can I pray for you?”

I’ve been making it a habit, when I finish a dinner party, a social gathering, a phone conversation or any other meeting with a friend or friends, to ask around the table or to a specific person one simple question…

…”How can I pray for you?”

I’m constantly amazed at how open, transparent, honest and vulnerable the replies can be, even from those who would not classify themselves as spiritual or religious, but who nonetheless seem quite open to being prayed for. Often, someone will share a health condition, a personal struggle, a business or relationship difficulty, a need for clarity, insight, wisdom or discernment, or some other trouble, worry or setback that they hadn’t brought up at any other point in the conversation. Often, I’ll pray with them right then and there, but other times I will, as an alternative to or in addition to that, jot that person and their specific need down in the prayer list I alluded to earlier so that their need stays top of mind in my prayer sessions for that week. If you adopt this practice, I encourage you to text, call or speak with that person one to two weeks afterwards to check in and see how they are doing with the particular issue you’ve been praying for them about. This can often lead to even more meaningful discussion and, for those who may not know or understand God, faith or salvation, the opportunity to open their eyes to love and light of salvation and hope that is within you.

Summary

So there you have it: prayer is powerful, but it can be tricky sometimes to weave it into your day, especially if you “overthink” or excessively intellectualize it. But approaching prayer from a more pure and simple, near-childlike perspective of openly speaking to God throughout the day in a form of contemplative prayer – even with single words, phrases or mantras – you can indeed “pray without ceasing”, without necessarily spending the entire day on your knees in your bedroom.

In addition, memorizing certain prayers, keeping a prayer list, praying regularly with a loved one, combining fasting and prayer, and regularly asking others how you can pray for them can be incredibly helpful for building prayer into your life in a meaningful and profound way that, as you’ve just learned, can literally change your biology and neurology for the better while simultaneously bringing you closer to daily union with God.