by Machida Shinobu: Public bathhouses have long been popular in Japan, for reasons of community as much as hygiene…

But when did they first emerge and how have they changed over the years? This article provides an overview of the history of sentō.

Sentō are public bathhouses that customers pay to use. But when did they first emerge in Japan? The earliest records date back hundreds of years.

A reference in Japan’s oldest collection of stories Konjaku monogatari (trans. Tales of Times Now Past) written from the end of the eleventh to the twelfth centuries indicates that there were sentō in Kyoto during the Heian period (794–1185). The appearance of the word yusen, meaning the fee paid to use a bath, in documents from the Kamakura period (1185–1333) suggests that public baths had been established by this time.

From early times large Buddhist temples would build structures within their precincts where local people could take steam baths for free. The goal of these bathhouses was as much about cleanliness as spreading Buddhism.

Threats to Public Morality

Sentō experienced a growth boom in the Edo period (1603–1868) as facilities used on a daily basis by common people.

According to a document of the time, the first public bathhouse in Edo (the former name for Tokyo) was built in 1591 by a man named Ise Yoichi. It was located by a bridge near what is now the Bank of Japan headquarters in central Tokyo. The sentō’s success led to the establishment of similar facilities. A decade later, there were bathhouses in every part of the city.

Records show that by 1810 there were 523 sentō in the city, demonstrating just how much Edoites loved a good soak.

Edo-period bathhouses can be divided roughly along the lines of whether they allowed mixed bathing or had separate areas for men and women. The Kansai region in western Japan boasted a lot of mixed baths. Edo had fewer, but the mixed sentō it did have were popular. For proprietors, having men and women together saved on costs as only one shared facility was required. One innovation was the introduction of yuna bathhouse girls to scrub male customers clean. The shogunate disapproved of the threats to public morality bathhouses posed, issuing a ban on mixed bathing and a limit on the number of yuna. However, its rulings were largely ignored in Edo.

At first, there were two main kinds of sentō. The furoya was based around steam baths, while the yuya centered on a large communal bathtub. Over time, the communal tub became standard, although confusingly it is now generally known as a furoya.

Open Structures

During the Edo period communal tubs were generally housed in dark, almost windowless rooms with low entranceways to prevent steam from escaping.

The start of the Meiji era (1868–1912) changed all this. Western criticisms led the Meiji government to ban mixed bathing (more successfully than the Edo shogunate) and to order that sentō should have a more open structure. In 1877, a new-style bathhouse, or kairyō–buro, opened in Kanda, Tokyo, with a steam vent in the high ceiling and a combined bathroom and changing area, so bathers no longer had to duck through the entrance after getting undressed.

This basic structure remains today, although features such as tiles and taps have been added through the years. In 1908 there were 1,217 sentō in Tokyo. According to materials produced by a bathhouse association, sentō reached their height of their popularity in 1968, when there were 18,325 located across the country.

Tokyo Sentō

Many Japanese people imagine sentō as looking like shrines or temples, built in what is known as the miyazukuri style. But this type of construction is basically limited to the Tokyo area. As the capital recovered and rebuilt after the Great Kantō Earthquake of 1923, carpenters with experience in constructing religious buildings applied their talents to making plain, traditional bathhouses more appealing to lift the spirits of residents. The distinctive curved karahafu gables of these striking new sentō were much admired and many later Tokyo bathhouses adopted the style, which is how it became associated with the capital. There is no standard architectural trend for sentō in the rest of Japan, however.

Handaazumayu is a plain-style bathhouse built around 1910. It can now be seen at the Meijimura museum in Inuyama, Aichi Prefecture.

Handaazumayu is a plain-style bathhouse built around 1910. It can now be seen at the Meijimura museum in Inuyama, Aichi Prefecture.

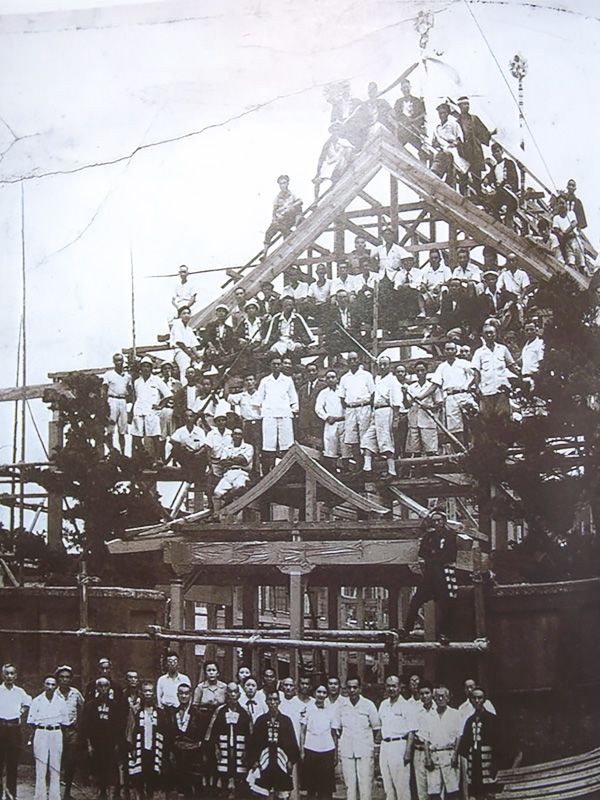

A miyazukuri-style bathhouse constructed in the late 1950s or early 1960s. It is said to have taken three months to build. (Photo courtesy Iidaka Construction)

A miyazukuri-style bathhouse constructed in the late 1950s or early 1960s. It is said to have taken three months to build. (Photo courtesy Iidaka Construction)

Apart from their external appearance, Tokyo bathhouses have a number of other features in common. They have changing rooms with high latticed ceilings, small courtyard gardens, and large murals painted above the baths.

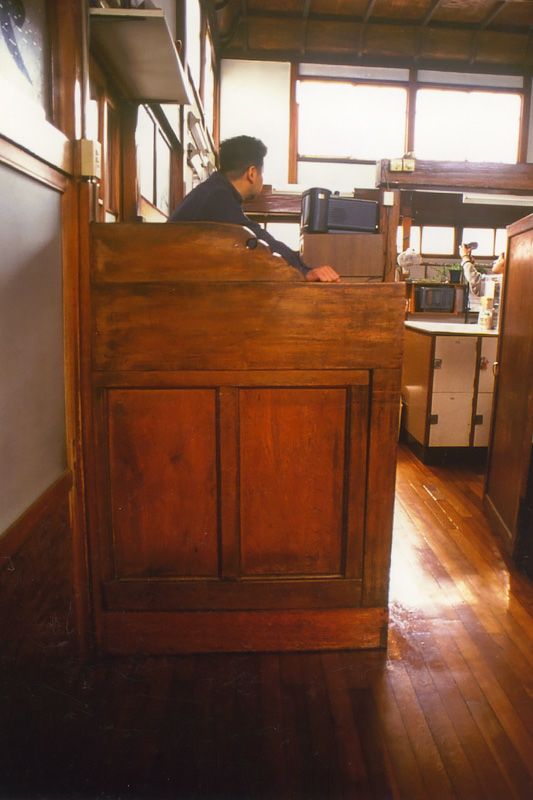

The bandai platform at Myōjin’yu, in Ōta, Tokyo. Customers pay entrance fees or buy soap and other items at these platforms, located in the changing rooms of older sentō. From the high vantage point they offer, attendants can observe the bathing area in case, for example, any customers appear to be unwell. Bandai in the Tokyo area tend to be particularly tall, with an average height of around 1.3 meters.

The bandai platform at Myōjin’yu, in Ōta, Tokyo. Customers pay entrance fees or buy soap and other items at these platforms, located in the changing rooms of older sentō. From the high vantage point they offer, attendants can observe the bathing area in case, for example, any customers appear to be unwell. Bandai in the Tokyo area tend to be particularly tall, with an average height of around 1.3 meters.

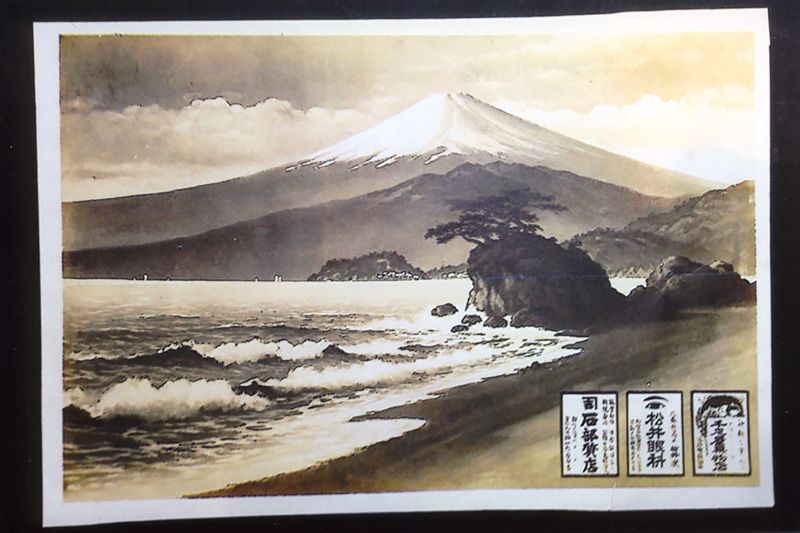

The murals often depict Mount Fuji. In 1912, the owner of Kikaiyu in Kanda asked the Western-style painter Kawagoe Kōshirō to produce a mural to please the children of his customers. Kawagoe was from near Mount Fuji in Shizuoka Prefecture, so he painted the famous peak. Fuji murals caught on quickly in Tokyo as bathers soaking under the paintings are made to feel like they are in the waters around the mountain, purifying their bodies as in some ancient ritual. This illusion is heightened by the placement of Tokyo bathtubs right against the wall. In other areas, many sentō do not have paintings, and tubs tend to be in the center of the room.

A work by Kawagoe Kōshirō, who painted the first Mount Fuji mural in a sentō. (Owned by Machida Shinobu)

A work by Kawagoe Kōshirō, who painted the first Mount Fuji mural in a sentō. (Owned by Machida Shinobu)

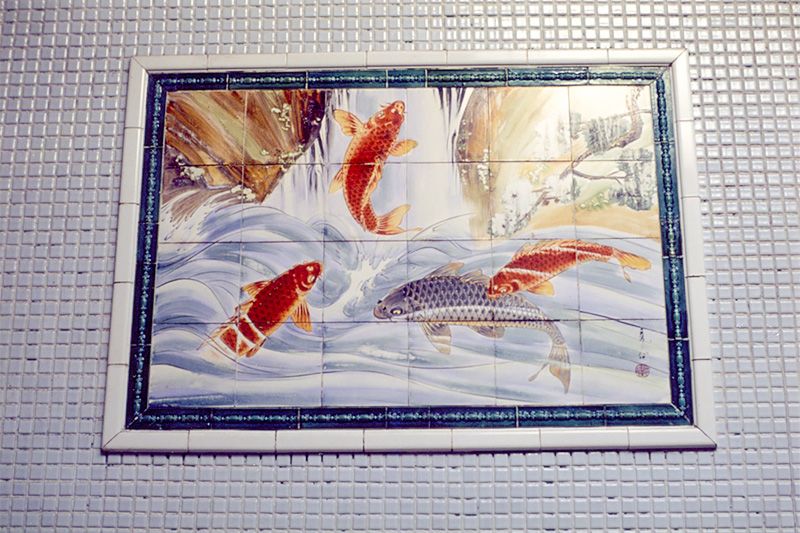

The courtyard gardens often have ponds with koi carp, in part because these are considered auspicious. The fish may also appear on tiles, which are almost always Kutani porcelain.

Paintings on tiles are a playful touch at sentō. They often depict koi carp swimming up a waterfall, which is an image associated with worldly success. This photo was taken at the now defunct Ninjin’yu in Kanazawa, Ishikawa Prefecture.

Paintings on tiles are a playful touch at sentō. They often depict koi carp swimming up a waterfall, which is an image associated with worldly success. This photo was taken at the now defunct Ninjin’yu in Kanazawa, Ishikawa Prefecture.

None of these various shared features are essential to the bathing experience. So why do proprietors bother to spend money on them? It may be connected to the traditional love of ostentatious display in old Edo. By creating a visually playful space away from the humdrum world, they also help their customers to forget their everyday cares.

The karahafu gables contribute to this atmosphere. They were once considered to lead the way to paradise, which is why they have been used variously to adorn religious buildings, hearses, and pleasure quarters.

Daikokuyu in Adachi, Tokyo, is known as the “king of sentō.” The front entrance is no longer used and customers go around to the right-hand side to enter.

Daikokuyu in Adachi, Tokyo, is known as the “king of sentō.” The front entrance is no longer used and customers go around to the right-hand side to enter.

The karahafu gable at Akebonoyu in Asakusa, Tokyo. Pale purple wisteria flowers transform the bathhouse entrance in May.

The karahafu gable at Akebonoyu in Asakusa, Tokyo. Pale purple wisteria flowers transform the bathhouse entrance in May.

Blending Tradition and Innovation

The number of sentō in Japan has dwindled to 4,000, or less than a quarter of the total in their 1960s heyday. One big factor is the steady spread of Japanese homes equipped with baths.

However, enhanced versions of bathhouses, known as “super sentō,” have been growing in popularity. One key difference between ordinary sentō and their super competitors is that the former have a maximum charge for use, established in local ordinances. Super sentō are free to set their own fees and accordingly offer more to customers, including such features as spaces to eat and parking areas. Families can comfortably spend several hours in these facilities.

Not to be outdone, bathhouse proprietors are sprucing up their standard sentō to take on the competition. These restored bathhouses are often referred to as “designer sentō.” To appeal to young people owners have often chosen to swap the traditional miyazukuri style for modern exteriors and install front lobbies instead of the old-fashioned bandai platforms used to observe both the male and female bathing areas. This latter switch from platforms to reception desks is helping to attract more female customers. As they add fresh touches to existing locations, designer sentō have come to be characterized by their blend of tradition and innovation.

Many of these have also added outdoor baths (rotenburo) and saunas. In some, it is possible to enjoy the pleasure of a cold soft drink or beer after taking a relaxing soak.

I should also note that while super sentō tend to shut down quickly if they are not lucrative, ordinary sentō are considered public facilities and so can benefit from local government subsidies.

Many Japanese people pride themselves on their love of baths. The country is blessed with many hot springs, but this is not the only reason for the popularity of bathhouses. For those who visit sentō, it is an opportunity to cleanse both the body and soul.