by (Mindful): Through loving-kindness and practicing awareness, you can connect more deeply with both yourself and others. Explore our new guide to lean into kindness and cultivate compassion every day…

Compassion helps us connect with others, mend relationships, and move forward while fostering emotional intelligence and well-being. Compassion takes empathy one step further because it harbors a desire for all people to be free from suffering, and it’s imbued with a desire to help.

What is Compassion?

Compassion is simply a kind, friendly presence in the face of what’s difficult. Its power is connecting us with what’s difficult—it offers us an approach that differs from the turning away that we usually do.

We begin with empathy—that feeling of connection. When we can acknowledge the commonality of the human condition, something beautiful happens: we diminish the subtle cruelty of indifference.

What is Self-Compassion?

Self-compassion involves treating yourself the way you would treat a friend who is having a hard time—even if your friend blew it or is feeling inadequate, or is just facing a tough life challenge. The more complete definition involves three core elements that we bring to bear when we are in pain: self-kindness, common humanity (the recognition that everyone makes mistakes and feels pain), and mindfulness.

Why Self-Compassion Is Important

Individuals who are more self-compassionate tend to have greater happiness, life satisfaction and motivation, better relationships and physical health, and less anxiety and depression. They also have the resilience needed to cope with stressful life events such as divorce, health crises, academic failure, and even combat trauma.

When we are mindful of our struggles, and respond to ourselves with compassion, kindness, and support in times of difficulty, things start to change. We can learn to embrace ourselves and our lives, despite inner and outer imperfections, and provide ourselves with the strength needed to thrive.

The Common Myths of Self-Compassion

Myth: Self-compassion will make us weak and vulnerable.

Truth: In fact, self-compassion is a reliable source of inner strength that confers courage and enhances resilience when we’re faced with difficulties. Research shows self-compassionate people are better able to cope with tough situations like divorce, trauma, or chronic pain.

Myth: Self-compassion is really the same as being self-indulgent.

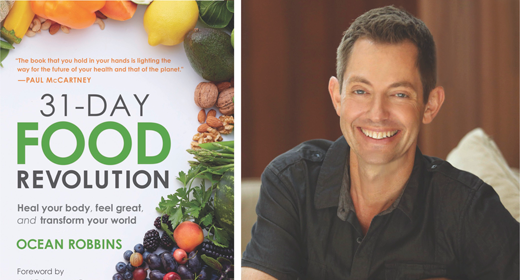

Truth: It’s actually just the opposite. Compassion inclines us toward long-term health and well-being, not short-term pleasure. Research shows self-compassionate people engage in healthier behaviors like exercising, eating well, drinking less, and going to the doctor more regularly.

Myth: Self-compassion is really a form of making excuses for bad behavior.

Truth: Actually, self-compassion provides the safety needed to admit mistakes rather than needing to blame someone else for them. Research shows self-compassionate people take greater personal responsibility for their actions and are more likely to apologize if they’ve offended someone.

Myth: Self-criticism is an effective motivator.

Truth: It’s not. Our self-criticism tends to undermine self-confidence and leads to fear of failure. If we’re self-compassionate, we will still be motivated to reach our goals—not because we’re inadequate as we are, but because we care about ourselves and want to reach our full potential. Self-compassionate people have high personal standards; they just don’t beat themselves up when they fail.

How to Practice Self-Compassion

Find Compassion: Write a Letter to Yourself

You can find your compassionate voice by writing a letter to yourself whenever you struggle or feel inadequate, or when you want to help motivate yourself to make a change. It can feel uncomfortable at first, but gets easier with practice.

Here are three formats to try:

- Think of an imaginary friend who is wise, loving, and compassionate and write a letter to yourself from the perspective of your friend.

- Write a letter as if you were talking to a dearly beloved friend who was struggling with the same concerns as you.

- Write a letter from the compassionate part of yourself to the part of yourself that is struggling.

After writing the letter, you can put it down for a while and then read it later, letting the words soothe and comfort you when you need it most.

A Self-Compassion Practice to Rewire Your Brain for Resilience

This is an exercise from resilience expert Linda Graham for shifting our awareness and bringing acceptance to the experience of the moment. It helps to practice this self-compassion break when any emotional upset or distress is still reasonably manageable—to create and strengthen the neural circuits that can do this shifting and re-conditioning when things are really tough.

- Any moment you notice a surge of a difficult emotion—boredom, contempt, remorse, shame—pause, put your hand on your heart (this activates the release of oxytocin, the hormone of safety and trust).

- Empathize with your experience—recognize the suffering—and say to yourself, “this is upsetting” or “this is hard!” or “this is scary!” or “this is painful” or “ouch! This hurts” or something similar, to acknowledge and care about yourself when you experience something distressing.

- Repeat these phrases to yourself (or some variation of words that work for you):

May I be kind to myself in this moment.

This breaks the automaticity of our survival responses and negative thought loops.

May I accept this moment exactly as it is.

From William James, considered the founder of American psychology: “Be willing to have it so. Acceptance of what has happened is the first step to overcoming the consequence of any misfortune.”

May I accept myself exactly as I am in this moment.

From humanist psychologist Carl Rogers: “The curious paradox is that when I accept myself exactly as I am, then I can change.”

May I give myself all the compassion I need.

Compassion is a resource for resilience, and you are as deserving of your own compassion as others are.

- Continue repeating the phrases until you can feel the internal shift: The compassion and kindness and care for yourself becoming stronger than the original negative emotion.

- Pause and reflect on your experience. Notice if any possibilities of wise action arise.

The RAIN of Self-Compassion Meditation

Tara Brach shares a four-step practice to offer ourselves a moment of compassion.

Self-compassion depends on honest, direct contact with our own vulnerability. Compassion fully blossoms when we actively offer care to ourselves. To help people address feelings of insecurity and unworthiness, I often introduce mindfulness and compassion through a meditation I call the RAIN of Self-Compassion. The acronym RAIN, first coined about 20 years ago by Michele McDonald, is an easy-to-remember tool for practicing mindfulness. It has four steps:

- Recognize what is going on

- Allow the experience to be there, just as it is

- Investigate with kindness

- Natural awareness, which comes from not identifying with the experience

You can take your time and explore RAIN as a stand-alone meditation or move through the steps in a more abbreviated way whenever challenging feelings arise.

R—Recognize What’s Going On

Recognizing means consciously acknowledging, in any given moment, the thoughts, feelings, and behaviors that are affecting us. Like awakening from a dream, the first step out of the trance of unworthiness is simply to recognize that we are stuck, subject to painfully constricting beliefs, emotions, and physical sensations. Common signs of the trance include a critical inner voice, feelings of shame or fear, the squeeze of anxiety or the weight of depression in the body.

A—Allowing: Taking a Life-Giving Pause

Allowing means letting the thoughts, emotions, feelings, or sensations we have recognized simply be there. Typically when we have an unpleasant experience, we react in one of three ways: by piling on the judgment; by numbing ourselves to our feelings; or by focusing our attention elsewhere.

We allow by simply pausing with the intention to relax our resistance and let the experience be just as it is. Allowing our thoughts, emotions, or bodily sensations simply to be doesn’t mean we agree with our conviction that we’re unworthy.

I—Investigating with Kindness

Investigating means calling on our natural curiosity—the desire to know truth—and directing a more focused attention to our present experience. Simply pausing to ask, what is happening inside me?, can initiate recognition, but investigation adds a more active and pointed kind of inquiry. You might ask yourself: What most wants attention? How am I experiencing this in my body? What am I believing? What does this feeling want from me?

N—Natural Loving Awareness

Natural loving awareness occurs when identification with the self is loosened. This practice of non-identification means that our sense of who we are is not fused with any limiting emotions, sensations, or stories.

Though the first three steps of RAIN require some intentional activity, the N is the treasure: A liberating homecoming to our true nature. There’s nothing to do for this last part of RAIN; we simply rest in natural awareness.

The RAIN of Self-Compassion is not a one-shot meditation, nor is the realization of our natural awareness necessarily full, stable, or enduring. Rather, as you practice you may experience a sense of warmth and openness, a shift in perspective. You can trust this! RAIN is a practice for life—meeting our doubts and fears with a healing presence. Each time you are willing to slow down and recognize, oh, this is the trance of unworthiness… this is fear… this is hurt…this is judgment…, you are poised to de-condition the old habits and limiting self-beliefs that imprison your heart. Gradually, you’ll experience natural loving awareness as the truth of who you are, more than any story you ever told yourself about being “not good enough” or “basically flawed.”

We each have the conditioning to live for long stretches of time imprisoned by a sense of deficiency, cut off from realizing our intrinsic intelligence, aliveness, and love. The greatest blessing we can give ourselves is to recognize the pain of this trance, and regularly offer a cleansing rain of self-compassion to our awakening hearts.

How Loving-Kindness Meditation Strengthens Compassion

If you’re familiar with meditation, then you’ve probably tried a basic loving-kindness practice. It involves bringing to mind someone you love, and wishing that they are safe, well, and happy—either out loud or to yourself. The practice continues by extending these well wishes outward to those around you: maybe a more neutral party, or even a difficult person in your life.

Repeating these phrases feels good in the moment, but they can also have long-term effects on our brain that stick with us after we’ve finished meditating. Daniel Goleman, author of Primal Leadership: Unleashing the Power of Emotional Intelligence and coauthor of Altered Traits, explains how this type of meditation can impact our mind and our outlook.

Goleman says loving-kindness practices strengthen compassion and empathetic concern: our ability to care about another person and want to help them.

“We find, for example, that people who do this meditation who’ve just started doing it actually are kinder, they’re more likely to help someone in need, they’re more generous and they’re happier,” Goleman explains. “It turns out that the brain areas that help us or that make us want to help someone that we care about also connect with the circuitry for feeling good. So it feels good to be kind and all of that shows up very early in just a few hours really of total practice of loving-kindness or compassion meditation.”

There are three different types of empathy, and these are strengthened when we practice loving-kindness. The two most common types of empathy are when you understand someone else’s perspective, and when you connect to them emotionally; but the final, most powerful type is empathic concern.

A Beginner’s Loving-Kindness Practice

Follow this simple loving-kindness practice to open the heart and mind towards a greater sense of compassion from Elisha Goldstein.

- Gently close the eyes if you feel comfortable doing that, or direct the eyes towards the floor while seated or lying down.

- Begin with a few deep breaths. Check in with where you’re starting this moment from, physically, emotionally, mentally.

- Consider a person in your life who is easy to care about. This could be a good friend, a partner, perhaps an animal. Imagine them sitting in front of you and looking into your eyes.

- Get a sense of your heart in this moment, and with intention say to this person, “May you be happy. May you be healthy in body and mind. May you be safe and protected from inner and outer harm. May you be free from fear, the fear that keeps you stuck.”

- Again breathing in and breathing out, reconnecting with your heart.

- Now incline your heart and mind towards yourself and saying to yourself, “May I be happy. May I be healthy in body and mind. May I be safe and protected from inner and outer harm. May I be free from fear, the fear that keeps me stuck.”

- And now breathing and breathing out, and considering a person in your life you don’t know too well. Perhaps the check-out person at your local market, or someone at work you’ve never spoken to.

- Connecting with your heart once again, and just like you did for the person who’s close to you saying now to them: “May you be happy. May you be healthy in body and mind. May you be safe and protected from inner and outer harm. May you be free from fear, the fear that keeps you stuck.”

- And breathing in and out, now bringing to mind someone in your life who you’ve had difficulty with. Someone you’re frustrated, irritated or annoyed with.

- And imagine them sitting here, looking into your eyes and with the same intention and heartfulness that you had for the person who it was easy to care for, now saying to them: “May you be happy. May you be healthy in body and mind. May you be safe and protected from inner and outer harm. May you be free from fear, the fear that keeps you stuck.”

- And now imagining, expanding this sense of heartfulness and intention throughout the entire world. All countries, all people.

- Saying to them: “May you be happy. May you be healthy in body and mind. May you be safe and protected from inner and outer harm. May you be free from fear, the fear that keeps you stuck.”

- And breathing in and breathing out, as we end this practice gently do another mindful check-in. Get a sense of how you’re feeling now, without any judgments. What emotions are present? Is this mind busy or calm?

- Perhaps ending by thanking yourself, and all the people who you included in this practice.

- And when you’re ready, gently open your eyes.

The Difference Between Empathy and Compassion

What Is Empathy?

Empathy is being able to perceive others’ feelings (and to recognize our own emotions), to imagine why someone might be feeling a certain way, and to have concern for their welfare. Once empathy is activated, compassionate action is the most logical response. Many confuse empathy (feeling with someone) with sympathy (feeling sorry for someone).

Empathy Can Be Taught

We may find it hard to empathize with some people. But that doesn’t mean we can’t strengthen our empathy muscles, according to psychiatrist and researcher Helen Riess, author of the book The Empathy Effect. Riess uses the acronym EMPATHY to outline the steps of her program:

E: Eye contact. An appropriate level of eye contact makes people feel seen and improves effective communication. Riess recommends focusing on someone’s eyes long enough to gauge eye color, and making sure you are face to face when communicating.

M: Muscles in facial expressions. As humans, we often automatically mimic other people’s expressions without even realizing it. By being able to identify another’s feelings—often by distinctive facial muscle patterns—and mirroring them, we can help communicate empathy.

P: Posture. Sitting in a slumped position can indicate a lack of interest, dejection, or sadness; sitting upright signals respect and confidence. By understanding what postures communicate, we can take a more open posture—face forward, legs and arms uncrossed, leaning toward someone—to encourage more open communication and trust.

A: Affect (or emotions). Learning to identify what another is feeling and naming it can help us better understand their behavior or the message behind their words.

T: Tone. “Because tone of voice conveys over 38 percent of the nonverbal emotional content of what a person communicates, it is a vital key to empathy,” writes Riess. She suggests matching the volume and tone of the person you are talking to and, generally, using a soothing tone to make someone feel heard. However, when a person is communicating outrage, moderating your tone—rather than matching theirs—is more appropriate.

H: Hearing. Too often, we don’t truly listen to one another, possibly because of preconceptions or simply being too distracted and stressed. Empathic listening means asking questions that help people express what’s really going on and listening without judgment.

Y: Your response. Riess is not talking about what you’ll say next, but how you resonate with the person you are talking to. Whether or not we’re aware of it, we tend to sync up emotionally with people, and how well we do it plays a role in how much we understand them.

How to Care Deeply Without Burning Out

Reining in over-empathy requires emotional intelligence; its underlying skill is self-awareness. You always need to be prepared to explore and meet your own needs. Whenever your empathy is aroused, regard it as a signal to turn a spotlight on your own feelings. Pause to check in with yourself: What am I feeling right now? What do I need now?

- Know the difference between empathy and compassion. Empathy is our natural resonance with the emotions of others, where we sense the difficulty someone might be feeling. Compassion is one of the many responses to empathy.

- Realize when you’re feeling overwhelmed. It’s inevitable that we will all experience burnout. What’s important is recognizing what’s happening and moving toward balance. Compassion implies a stability of attention and caring in a wise and balanced way—caring about yourself and others.

- Recognize that you can’t change others. Compassion also implies a wisdom and intelligence to know that it’s not up to you to fix the world for others. You can’t function if you’re just taking in others’ pain all the time. There’s a balance that’s crucial: You can acknowledge the pain, you can want to help, but you have to recognize that you can’t change other people’s experience of the world. That’s the letting go. Dan Harris puts it this way: “My father says the hardest thing about having kids is letting them make their own mistakes. That’s compassion with equanimity.”

How to Cultivate Compassion Every Day

How to Be More Compassionate at Work

Have you ever dreaded going into work because the people around you were in a negative spiral of energy? We are emotional beings and we can’t help but be affected by the varying moods and interactions we have with others. Life is always changing and this constant change can create difficult thoughts and emotions, which can flow into the workplace. The silver lining is that if we can meet suffering at work with concern and care, compassion naturally arises. Work environments that cultivate compassion create a much more positive and productive place to work.

Compassion in the Workplace:

- Take greater notice of your fellow employees’ psychological well-being. For example: If an employee has experienced a loss, such as a divorce or death in the family, someone should contact that employee within 24-48 hours and offer help. A study in 2012 demonstrated that people who act compassionately are perceived more strongly as leaders and that perceived intelligence (i.e., how clever and knowledgeable the person is) bridges the relationship between compassion and leadership.

- Encourage and display more positive contact among employees. In many workplaces where I consult, there are meeting spaces that can be utilized for informal groups and gatherings. Planned groups can be encouraged weekly or monthly and allow for more opportunities to notice when someone needs help or support and then to offer it.

- Invite more authenticity and open communication in the workplace. If we can keep the communication lines open with respect and kindness, we allow for time to talk about what may need attention and/or empathic connection.

- Take on the perspective of the other person. In other words, this person is “just like me.” This is also known as “cognitive empathy,” or simply knowing how the other person feels and what they might be thinking. This type of empathy can help in negotiating or motivating people to give their best effort.

- Start with self-compassion. In order to truly have compassion for others, we must have compassion for ourselves.

How to Be More Compassionate Through Email

Emailing feels almost like a conversation, but without the emotional signs and social cues of face-to-face interactions. If there’s any challenging content to convey—and if you’re sending an email out to more than one person—it’s easy for problems to arise. Here’s how you can communicate more thoughtfully and compassionately via email.

- Keep it short and sweet. Using fewer words usually leads to more clarity and greater impact. Your message can easily get lost in the clutter, so keep it simple.

- Ask yourself—should I say this in person? Some messages are just too touchy, nuanced, or complex to handle by email. You may have to deliver the message in a phone call, where you can read cues and have some give and take. Then, you can follow up with a message that reiterates whatever came out of the conversation.

- Notice your tone. If there’s emotional content, pay close attention to how the shaping of the words can create a tone. If you have bursts of short sentences, for example, it can sound like you’re being brusque and angry.

- Consider your role. If there’s a power dynamic (for example, you are writing to somebody who works for you or who reports to you), you need to take into account how that affects the message. A suggestion coming from a superior in an email can easily sound like an order.

A Mindful Emailing Practice

- Begin by composing an email as usual. Try using the Enter key more. Shorter paragraphs are easier to read on screens.

- Then stop, and enjoy a long deep breath. Put your hands in front of you and wiggle your fingers to give them a little break. Now, lace your fingers together and place them behind your head. Lean back and give your neck a little rest. Now you’re in a good position for the next step.

- Think of the person, or people, who are going to receive the message. How are they reacting? How do you want them to react? Do they get what you’re saying? Should you simplify it some? Could they misunderstand you and become angry or offended, or think you’re being more positive than you intend when you’re trying to say no or offer honest feedback?

- Look the email over again and make some changes if necessary. Notice any spelling or grammar errors you may have missed the first time.

- Don’t send your email right away. If it’s not time-sensitive, leave it as a draft, compose some other messages or do something else, and then come back to it.

- Take one last look, and press send.

How to Be More Compassionate When We Speak

Bringing awareness, or mindfulness, to the way we communicate with others has both practical and profound applications. During an important business meeting, or in the middle of a painful argument with our partner, we can train ourselves to recognize when the channel of communication has shut down. We can train ourselves to remain silent instead of blurting out something we’ll later regret. We can notice when we’re over-reacting and need to take a time-out.

We begin practicing mindful communication by simply paying attention to how we open up when we feel emotionally safe, and how we shut down when we feel afraid. Just noticing these patterns without judging them starts to cultivate mindfulness in our communications. Noticing how we open and close puts us in greater control of our conversations.

Practicing mindful communication often brings us face to face with our anxieties about relationships. These anxieties are rooted in much deeper, core fears about ourselves, about our value as human beings. If we are willing to relate to these core fears, each of our relationships can be transformed into a path of self-discovery. Simply being mindful of our open and closed patterns of conversation will increase our awareness and insight. We begin to notice the effect our communication style has on other people. We start to see that our attitude toward a person can blind us to who the person really is.

What Does Compassionate Listening Look Like?

1. The first step is “listening with the whole body.” This means literally tuning in to the person who is speaking.

“Compassionate” body language includes:

- Turning toward the speaker, not just with your head, but positioning your whole body to face the speaker.

- Open body language, such as arms and legs not crossed (and certainly no distractions, like a cell phone, in your hands!).

- “Approach” signals, such as learning toward, not leaning back from the speaker. This counters our usual instinct to “avoid” or withdraw from suffering, even at the subtle level of body language.

In previous studies, people who felt high levels of compassion spontaneously shifted into this posture. Just assuming this body language can make it easier to make a compassionate connection with someone.

2. The next step is called “soft eye contact.” When it comes to listening, eye contact is usually better than avoiding eye contact. But the most supportive and comfortable eye contact isn’t gazing deeply into a person’s eyes, or staring them down without a break in eye contact. Instead, it’s a soft focus on the triangle created by a person’s eyes and mouth. This allows you to take in the speaker’s full facial expressions. It also includes occasional breaks in eye contact to reduce what can be an uncomfortable intensity.

3. The last step is to offer “connecting gestures.” These gestures let a person know that you are feeling connected to what they are saying. The most appropriate connecting gestures are smiles and head nods, without interrupting the speaker. Connecting gestures encourage a speaker to continue, and often feel more supportive than when the listener jumps in verbally to make comments. When appropriate, touch is an even more powerful connecting gesture. Previous research has shown that people can more easily recognize compassion through touch—such as a comforting hand on your shoulder—than through voice or facial expressions.

How to Add a Healthy Dose of Self-Compassion to Your Meals

A lack of self-compassion closes the door to learning about our habits, patterns, triggers and needs when it comes to food. By adopting a forgiving and curious attitude instead, you can foster a healthy relationship with eating and food and yourself that can open the door to improved health and happiness.

1. Give up black-and-white thinking.

Embrace the fact that healthy eating is flexible and can include a wide variety of foods, some of which are richer than others, such as a pizza. And sometimes the healthier choice may be the richer choice.

For example, which would be a healthier choice at a party: Pizza or salad? The salad is only healthier if that’s what you really want. Otherwise, you might feel deprived and end up overeating later. Enjoying pizza mindfully as part of a celebration allows for the many roles that food plays in our lives. We can often end up feeling satisfied with less when it does.

2. Become aware of how you talk to yourself when eating.

Does a tape start running in your head that admonishes you not to eat too much or not to eat certain types of foods? Or that you’re a failure if you do? Write down what you say to yourself.

3. Write down kind responses to your inner critic.

Have readily available responses that you can “turn on” when you hear yourself starting to go down the familiar road of negative self-talk.

4. Practice those kind responses to yourself.

Every time you hear yourself talking negatively to yourself about your eating, take a moment to be kind to yourself. Try carrying around a small notebook with your new messages to refer to. Remember, the first time you do something differently is the hardest. Every time you do it thereafter, it gets easier.