by Olga Mecking: Straightforwardness is so intrinsic in Dutch society that there’s even a Dutch word for it: ‘bespreekbaarheid’ (speakability) – that everything can and should be talked about…

I’d only been living in Amsterdam for a year when we met my husband’s friends in one of the many cafes and bars in the city’s famous Vondelpark.

We chose our seats and waited, but the waiter was nowhere to be seen. When he finally materialised, seemingly out of nowhere, he didn’t ask ‘What would you like to order’, or ‘What can I get you?’. He said ‘What do you want?’. Maybe it was the fact that he’d said it in English, or maybe he was just having a bad day, but I was shocked nonetheless.

My Dutch teacher later explained that the Dutch are very direct – and nowhere are they so direct as they are in Amsterdam.

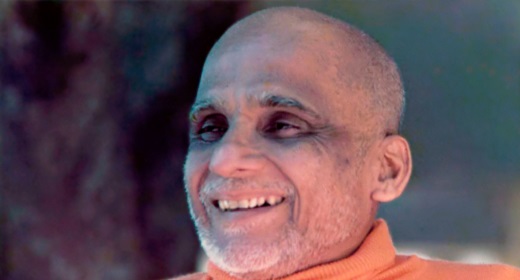

Ben Coates, who wrote Why the Dutch Are Different, moved to the Netherlands from Great Britain eight years ago. He recalls similar experiences, specifically one situation when he got a haircut and a friend immediately pointed out that it didn’t suit him at all.

“I think the Netherlands are a place where… no-one is going to pretend. [For example], when you say something in a business meeting that is not a very smart suggestion, people will always point it out,” he said.

To Coates, the differences between his native Britain and the Netherlands were immediately noticeable. In Great Britain, he says, people tend to communicate and behave in a way that minimises offense to other people.

“You don’t talk too loudly on the train because it’s not too nice for the people in your compartment; you don’t play your music too loud in your apartment because it’s not so nice for your neighbours; there is this constant calibrating of your own behaviour,” Coates explained. But in the Netherlands, there is “the sense that people have the right to say whatever they want and be as direct as they want. And if other people don’t like that, it’s their fault for getting offended.”

Ben Coates: “[There is] the sense that people have the right to say whatever they want and be as direct as they want” (Credit: Manfred Gottschalk/Getty Images)

To many foreigners, this give-it-to you-straight mentality can come across as inconsiderate, perhaps even arrogant. One time, I found myself at the supermarket staring with disbelief at the groceries that had spilled out of my hands onto the floor. Within seconds, I was surrounded by no fewer than 10 Dutch people, all of them giving me advice on what to do. But not one lifted a finger. To me, the situation was obvious: I needed help immediately. But the Dutch saw it differently: unless I specifically asked for help, it probably wasn’t necessary.

“Others may think that we don’t have empathy. And maybe that is so because we think truthfulness goes before empathy,” explained Eleonore Breukel, an interculturalist who trains people to communicate better in multicultural environments.

In the end, it all comes down to differences in communication patterns, said Breukel, who is Dutch but has lived all over the world. She believes the Dutch tendency to be very direct has to do with straightforwardness, which in turn is connected to the historical prevalence of Calvinism in the Netherlands (even though, according to Dutch News, the vast majority of Dutch people don’t associate with any religion today).

Dutch prince William the Silent converted from Catholicism to Calvinism, which had a large impact on national identity (Credit: Lanmas/Alamy)

After the start of the Reformation in the 16th Century, Calvinism spread to France, Scotland and the Netherlands. But it only had noticeable impact in the latter, where it coincided with the fight for independence against Catholic Spain, which ruled over the Netherlands from 1556 to 1581. In 1573, the Dutch prince William the Silent (called Willem van Oranje in Dutch), the founder of the Royal House of Orange that rules the Netherlands today, converted from Catholicism to Calvinism and united the country behind him. As a result, the Calvinist religion had a large impact on national identity because the Dutch associated Catholicism with Spanish oppression.

From that moment on, “Calvinism dictated the individual responsibility for moral salvage from the sinful world through introspection, total honesty, soberness, rejection of ‘pleasure’ as well as the ‘enjoyment’ of wealth,” writes Breukel in an article on Dutch business culture published on her website.

This straightforwardness is so intrinsic in Dutch society that there’s even a Dutch word for it: bespreekbaarheid (speakability) – that everything can and should be talked about; there are no taboo topics.

The Dutch word bespreekbaarheid (speakability) means everything can and should be talked about (Credit: Ian Dagnall/Alamy)

In fact, directness and the idea of transparency that goes with it is a highly desirable trait to the Dutch. Many of the older houses in the Netherlands have big windows, allowing visitors – if they so wish – to peep inside.

“There is a totally different concept of privacy,” Coates said, noting the tendency of the Dutch people to discuss intimate topics in public.

“You sit in a restaurant with a friend and they will happily, in a room full of strangers, talk quite loudly about their medical problems or their parents’ divorce or their love life. They see no reason to keep it a secret.”

In fact, from an outside point of view, it seems that every topic, no matter how difficult, should be up for debate. The Netherlands is unique in the way it treats topics such as prostitution, drugs and euthanasia. The latter is fully legalised but highly controlled, while the Red-Light District is a famous part of Amsterdam. While marijuana is no longer entirely legal, authorities have a so-called tolerance policy where coffee shops are not prosecuted for selling it.

But Breukel disagrees with the premise that the Dutch don’t have taboo topics. “We don’t discuss salaries, we don’t discuss pensions. Anything to do with luxury. We don’t talk about how beautiful our house is. We don’t discuss how big our car is,” she added.

Moreover, she said that the Dutch don’t want to acknowledge anything that might hint at inequality or power relationships. This is because of the so-called poldermodel, the Dutch practice of policymaking by consensus between government, employers and trade unions. The word ‘polder’ refers to pieces of land reclaimed from the sea. According to The Economist, to make the building of polders possible and to guard the country from the ever-present threat from the sea, the Dutch had to cooperate and work well together. This seeped down to family life where children’s voices count almost as much as those of the parents.

Many of the older houses in the Netherlands have big windows, allowing passers-by to look inside (Credit: Inigo Cia/Getty Images)

“We have an egalitarian culture. And in that egalitarian culture, we don’t want to make a difference between the boss and the employee,” Breukel said. In other words, there are rules of behaviour that everyone has to follow, and that, again, is visible in language. Proverbs such as ‘Doe maar normaal, dan ben je al gek genoeg’ (just be normal, that’s already crazy enough) or ‘Steek je hoofd niet boven het maaiveld uit’ (don’t put your head above the ground) are there to remind us that we are all the same.

As for me, I am learning to communicate better in the direct, Dutch way. Breukel advised me to start with the subject – for example, ‘I would like an appointment’ – instead of listing all the reasons why I should see the doctor. I’ve also learned to ask for help, instead of expecting it to be offered. And although I may complain about Dutch directness, I’m grateful to live in a country that allows me to be just that.

![Ben Coates: “[There is] the sense that people have the right to say whatever they want and be as direct as they want” (Credit: Credit: Manfred Gottschalk/Getty Images) Ben Coates: “[There is] the sense that people have the right to say whatever they want and be as direct as they want” (Credit: Credit: Manfred Gottschalk/Getty Images)](https://ychef.files.bbci.co.uk/624x351/p05wq29d.jpg)