by Katy Scott: Terrorist. Misogynist. Fanatic. The portrayal of Arab men can often be one-dimensional and unflattering, particularly in Western media…

But two female photographers have sought to confound these stereotypes.

The idea was to present these men as they are, beyond the stereotype, without labeling them as anything.

Scarlett Coten’s “Mectoub” series — recently on display at the Arab World Institute in Paris — explores the subject of masculinity across the region.

Iraqi-Canadian photographer Tamara Abdul Hadi, meanwhile, is currently putting together a book of photos on the subject.

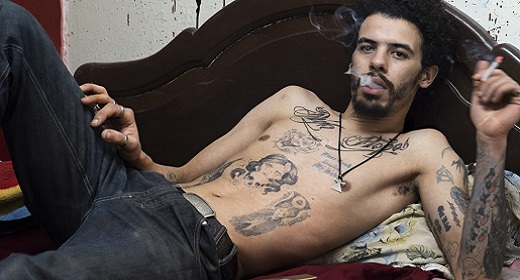

A portrait of Abdel from the “Mectoub” series shot in Marrakech, Morocco. Credit: Scarlett Coten

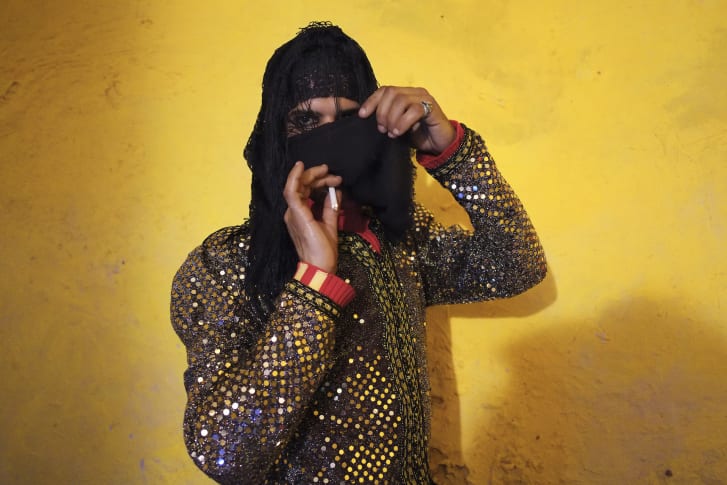

Inspired by the shifting atmosphere following the Arab Spring and her own curiosity about masculine identity, French photographer Coten spent five years from 2012 to 2016 photographing subjects in Algeria, Egypt, Jordan, Lebanon, Morocco, Tunisia and the West Bank.

Her portraits are unconventional, with men staring directly at the viewer, juxtaposed against crumbling buildings and colorful interiors. Some wear high heels, others wrap themselves in scarves or fur.

“The goal is not to portray them as feminine,” Coten tells CNN. “In a face-to-face meeting we are vulnerable because we reveal ourselves. And this unveiling gives birth to something that is more sensitive.”

Coten won the 2016 Leica Oskar Barnack Award for her series of striking photographs.

“Mectoub” is a play on words between the Arabic “maktub” which means “it is written” and the colloquial French word “mec” for “guy.”

While Coten spent 15 years working as a photographer in Arab countries — including a stint in the barren Egyptian desert living with Bedouin tribes — she remained conscious of the fact that she was foreign, French and, most importantly, female.

But she feels her role as an outsider played to her advantage as she says the men felt they could confide in her. “They can tell me, ‘I do not believe in Allah’, ‘I do not practice Ramadan’ … things they do not tell their loved ones.”

This is perhaps why the men lay bare their true identities in the photographs, she says.

A portrait of Khalid in Amman, Jordan. Credit: Scarlett Coten

Coten likens her creative process to a performance, except one with little direction. She simply tells her subjects to try not to pose and to look directly at her.

“To look someone in the eyes puts us in a situation of vulnerability, and therefore to be closer to who we truly are,” she says.

In most of the portraits the men are looking directly into Coten’s eyes, and not at the lens.

‘Soft, human, vulnerable’

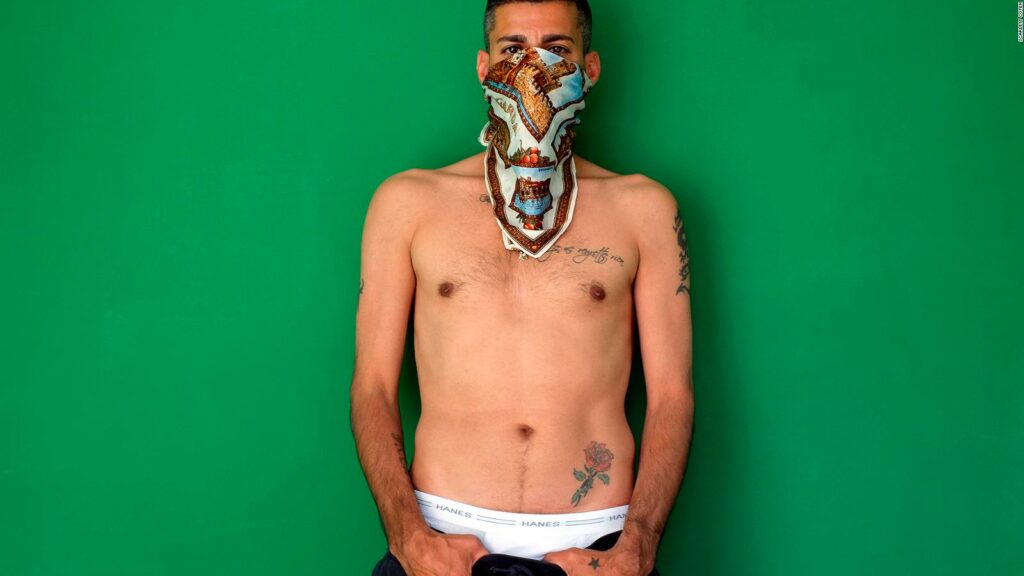

The subject matter explored by Coten echoes that of Iraqi-Canadian photographer Tamara Abdul Hadi.

She drew from her personal experiences as an Arab woman to capture the beauty and vulnerability of her male counterparts for her 2009 to 2014 project, “Picture an Arab Man,” which she is currently working into a book.

Her intimate shots implore the viewer to reconsider their preconceptions.

Abdul Hadi describes the men she photographed as being completely taken aback by how “soft” they turned out — a far cry from many mass media portrayals of men in the region.

“A lot of that softness maybe they don’t see in themselves unless you show it to them having captured it,” she says.

A report by gender equality organization Promundo and UN Women earlier this year found that a majority of men in the Middle East don’t support gender parity, perhaps suggesting some of the harsher perceptions around Arab patriarchy.

Growing up in the UAE and later Montreal with Iraqi parents, however, Abdul Hadi says her gentler representation of the Arab man is exactly how she sees those that surrounded her throughout her life.

She chose to photograph the men she encountered on the streets up-close and semi-nude, so that the viewer is not given any clue about their culture or religion.

“I wanted them all to melt into one look of an Arab man who is human and who is sometimes vulnerable, sometimes gentle.”

Both photographers say they hope their work will encourage people to think differently about the Middle East and particularly about men in the region.

For Abdul Hadi, the most rewarding response to her series is when people tell her they’ve never been that close to an Arab man.

For Coten, it is when she exhibits in the Middle East and Arabic people thank her for her work.

“It is important to them that I am showing a different picture of these men,” says Coten. “And they find themselves in these images.”