by Brad Stulberg: It may seem daunting, but a period of disorder from time to time can be a beneficial break from stress…

If you’ve ever pushed hard or cared deeply about something then you’ve probably experienced a feeling of being lost. Perhaps this manifests as being unsure of what to do next; unsure of how to do it; or even unsure of why you’re doing what you’re doing in the first place. This, says the spiritual teacher Rob Bell, “is a very normal dimension to the human experience…when you feel lost, whatever you do, don’t fight it; just bear witness to it; acknowledge it.”

Bell has a framework for growth that goes like this: orientation -> disorientation -> reorientation.

Another well-known spiritual teacher, the Franciscan Friar Richard Rohr, often speaks about transformation as a process of order -> disorder -> reorder.

This is quite similar to a framework that I’ve written about extensively, and one that is backed by over 100 years of science: stress -> rest -> growth.

The challenge for many, myself included, is what to do during the off phases.

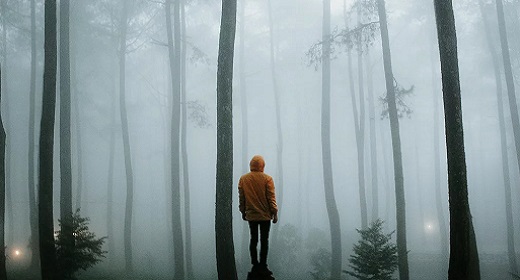

For someone who is accustomed to being on, to having things under control and figured out, disorientation, disorder, and even just rest can be discombobulating. These are the phases that almost always look better once you are on the other side of them. It’s easy to talk about the merits of disorientation and disorder from a place of reorientation and reorder. It’s much harder when you’re in the thick of them and feeling lost.

As Bell says, the natural tendency is to fight being lost; or perhaps to shut-down altogether in the face of disorientation and disorder. Generally, this isn’t helpful. Decades of psychological science shows that suppression and repression have negative effects.

But the flip-side, to romanticize and dwell in disorientation and disorder, isn’t helpful either. It’s not fun to be lost. We shouldn’t celebrate it. Ruts build on themselves. Science clearly shows that mood tends to follow action, not the other way around— sometimes the best way out of being lost is to just start doing something.

Herein lies the paradox: It’s counterproductive to suppress or repress disorientation and disorder. But it’s also counterproductive to romanticize and dwell in them. What is one to do?

Perhaps the answer is simply to pay attention — ideally with a non-judgemental mind and an open heart.

Disorientation and disorder aren’t good or bad. They just are. The minute we judge them as good, as being desirable and key phases to growth, we’re liable to sit and stew in them for too long. The minute we judge them as bad and start suppressing and repressing them, we’re liable to miss out on what these phases have to teach us, and, ironically, also overextend their stay. But if we pay close attention to what is happening inside of us during these phases, and do so without judgement, the next steps tend to emerge on their own. In other words: we’ve got to be with disorientation and disorder before we do something about them.

This is true for individuals and for organizations. It’s true for small communities and entire nations. It’s the stuff of not only spiritual teachers but also science. Evolution is literally a process of order -> disorder -> reorder. Rush through disorder without listening to what it is telling you and adapting accordingly and you get selected out. But the same thing happens if you dwell in disorder for too long.

- Order -> disorder -> reorder.

- Orientation -> disorientation -> reorientation.

- Stress -> rest -> growth.

Whether we’re talking about a marriage, a career, training for a marathon, building a business, writing a book, or walking a spiritual path, the middle phases — which, for anything you care deeply about, are unavoidable — are often the hardest. They are immune to strategizing and planning and controlling. There’s a risk in spending too little time in them and there’s an equal risk in getting stuck in them for too long. Perhaps the best thing to do is cultivate the capacity to name when you’re in these phases and then pay close attention to what is happening. It is in this way that you’ll learn when to keep being and when — and what — to start doing.