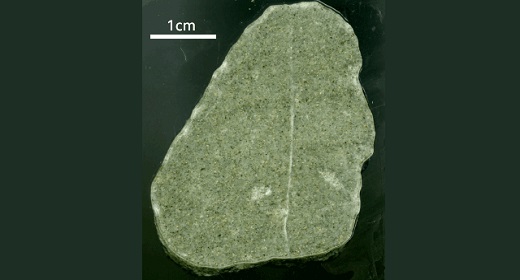

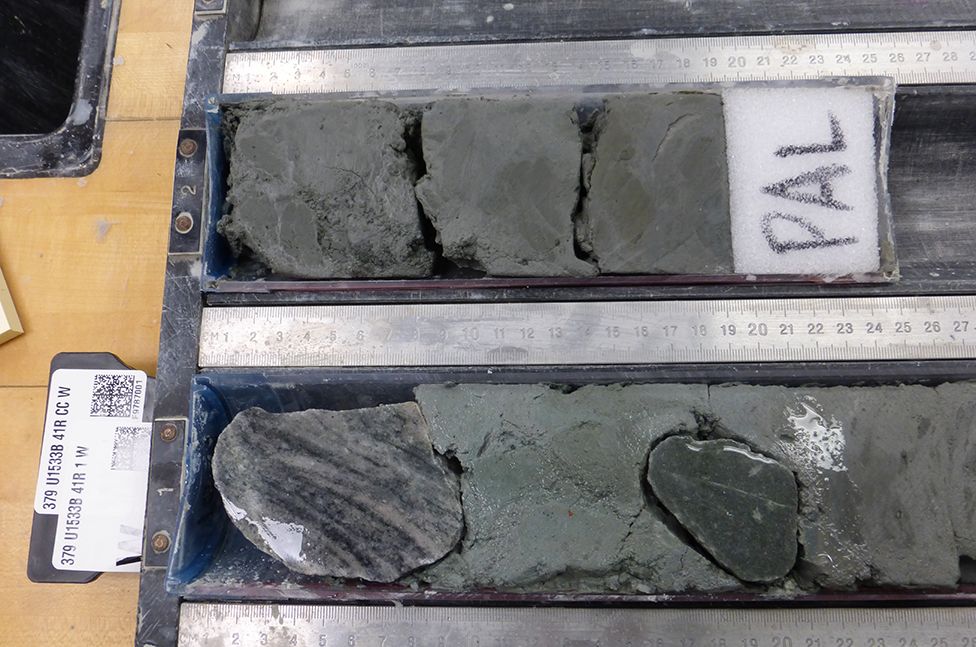

by Jonathan Amos: It’s an unassuming rock, greenish in colour, and just over 4cm in its longest dimension. And yet this little piece of sandstone holds important clues to all our futures…

The scientists who found it say it shouldn’t really have been there.

It’s what’s called a dropstone, a piece of ice-rafted debris.

It was scraped off the White Continent by a glacier, carried a certain distance in this flowing ice, and then exported and discarded offshore by an iceberg.

What’s remarkable about this particular cobble is that researchers can say where it originated.

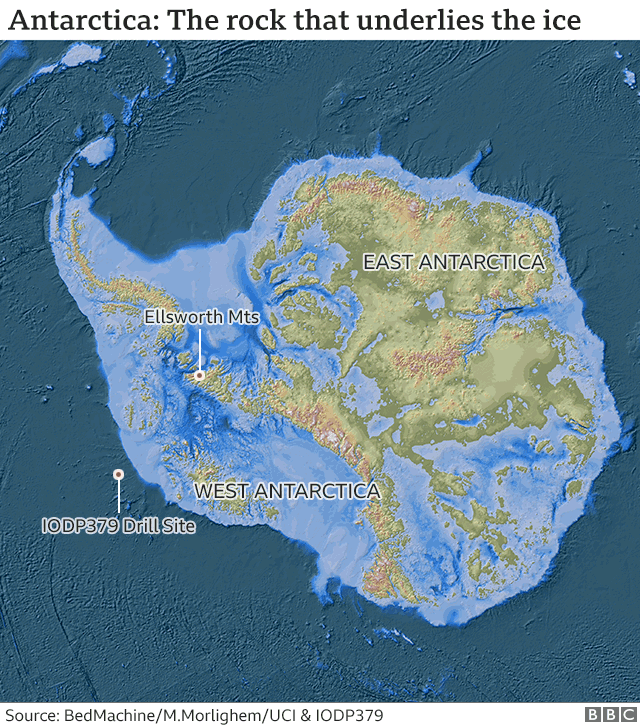

Using the latest “geo-fingerprinting” techniques, they’ve established with strong confidence that it comes from the Ellsworth Mountains – some 1,300km from where the rock was pulled up from the floor of the Amundsen Sea by a drilling ship.

The conundrum is that the Ellsworths – the tallest range in Antarctica – are in the far-interior of the continent, and it’s highly unlikely a rock like this could survive being ferried so far under an ice sheet to get to the coast to be then despatched in a large, frozen, floating block.

“In our view of observations of that material, it would not withstand a great deal of transport, with deposition and then re-transport over multiple steps of a cycle. And, furthermore, it probably would not hold up well to a great deal of interaction between the ice sheet and the bedrock. It would be destroyed and disaggregated,” Christine Siddoway, professor of geology at Colorado College, US, told BBC News.

IMAGE COPYRIGHTMICHAEL STUDINGER/NASA

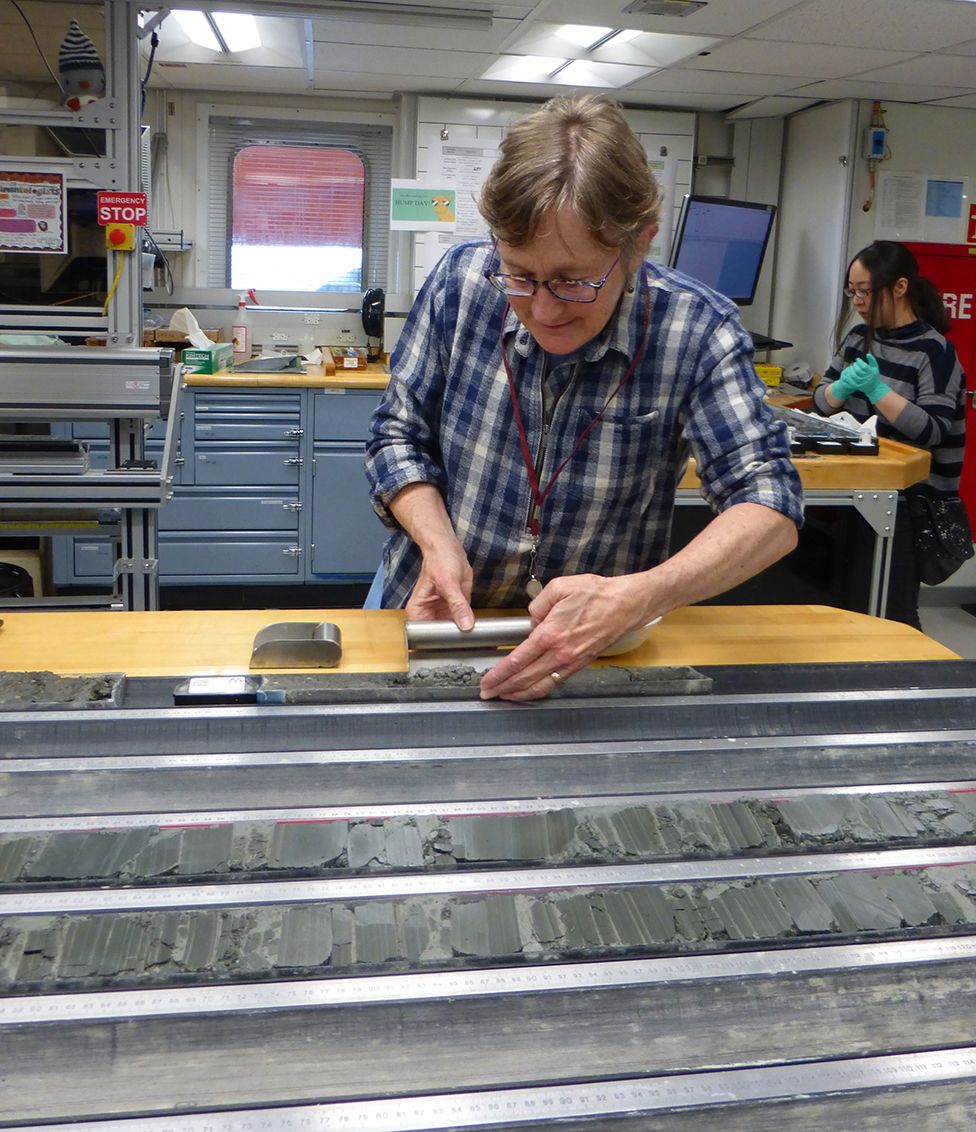

IMAGE COPYRIGHTMICHAEL STUDINGER/NASASo how did it get to travel so far? The answer is in the age of the deposits collected by the Joides Resolution ship on its International Ocean Discovery Program (IODP) “Expedition 379” cruise in 2019.

They’re mid-Pliocene in the geologists’ timeline. That’s about three million years ago.

The mid-Pliocene is a fascinating period in Earth history because of its strong echoes of today. It was the last time the atmosphere carried the same concentration of the greenhouse gas carbon dioxide – at over 400 parts per million.

Temperatures back then were significantly warmer, perhaps by 2-3 degrees globally, and sea-levels were also higher, possibly by as much as 10-20m above the modern ocean surface.

And this is where our small green sandstone rock comes into the story.

Those mid-Pliocene sea-levels imply the West Antarctic Ice Sheet, or at least significant parts of it, had melted away – and that in its place was a large open seaway.

This is hard to imagine when you look at maps of Antarctica today; we view its ice covering as a continuous solid mass. But take the ice off and you are essentially left with a great archipelago – a series of major islands.

It explains how the cobble could travel so far.

Glacier ice at the Ellsworth Mountains picked it up and then produced an iceberg locally to float it more than a thousand kilometres across the open seaway to drop it in the place Expedition 379 eventually recovered it.

“Our findings do confirm that the ice sheet can disappear fairly rapidly and also that it can re-establish itself fairly readily,” explained Prof Siddoway.

“We read from very detailed records – that we’re striving to make even more detailed – that the ice sheet has collapsed back in a considerable extent, specifically in the middle Pliocene.

“This is an interval, if we read current literature from climate modellers, that we may be entering… The climate conditions of the Pliocene are what we are expected to enter. And if warming continues at the rate that it is now, we may stay there.”

IMAGE COPYRIGHTVIV CUMMING/IODP/EXP379

IMAGE COPYRIGHTVIV CUMMING/IODP/EXP379No-one expects the West Antarctic Ice Sheet to collapse anytime soon, but the little sandstone cobble is a warning, scientists believe, of the conditions we could eventually re-create if we don’t soon get on top of the climate crisis.

Prof Siddoway presented details of the IODP Expedition 379 research at this week’s European Geosciences Union (EGU) General Assembly. Normally held in Vienna, Austria, #vEGU21 has been convened online this year because of Covid restrictions.

IMAGE COPYRIGHTCHRISTINE SIDDOWAY

image captionThe green sandstone (lower-right) embedded in the muds drilled from the ocean floor