by Lacey Rose: He understands if you are delighted by his return to TV. But like the subjects he’ll cover on Apple’s ‘The Problem With Jon Stewart,’ his comeback is a little more complicated: “It’s ‘The Daily Show,’ but less entertaining — but also maybe more complete…”

Jon Stewart knows that you’re likely to position his forthcoming Apple TV+ series as his hotly anticipated return to TV. It’s just that he’d rather you didn’t.

“It just feels arrogant,” says the longtime host, who’s remained largely out of the public eye since he stepped down from The Daily Show in 2015, emerging only sporadically to promote a film, riff on-air with pal Stephen Colbert or lobby for veterans’ rights on Capitol Hill. At one point, “He’s back” was the proposed tagline for the new show, but Stewart convinced his new partners to reconsider. He wasn’t as persuasive when it came to the first promo, which is set to a Bruno Mars song featuring the lyric, “Guess who’s back again?”

“I understand that it’s a business and they’ve got to do what they’ve got to do,” says Stewart, “but I do want to be clear that that’s not me.”

What is him? Nearly everything else about The Problem With Jon Stewart, which will roll out biweekly episodes beginning Sept. 30. The concept — a current affairs series that tackles a single issue, or “problem,” every episode — is some two years in the making. In fact, Stewart first shared its loose shape with former HBO head Richard Plepler over lunch in November 2019.

“I remember Jon saying very succinctly, ‘Noise is the enemy, clarity the goal,’” says Plepler, who brought the show to Apple as the first project under his producing deal there. It was an easy yes for the then-fledgling streaming service, which has since managed to muscle into the conversation with a mix of scripted (Ted Lasso) and talk (The Oprah Conversation). Snagging Stewart’s first TV series since he wrapped his 16-year, Emmy-stuffed run on The Daily Show was widely viewed as a marketing coup, and it could prove a viewership one, too.

Earlier this year, Stewart hired a showrunner (news veteran Brinda Adhikari) and head writer (comedian Chelsea Devantez), then assembled a staff very different from the mostly white comedy writers that made up his last one. Of the series’ nine writers, “most of them have never worked on a comedy show,” says Adhikari, who rattles off résumés that include social work and the military. “It’s not like we were just hiring writers from The Harvard Lampoon.” Collectively, the staff — some of whom appear on air in snippets from the office — mapped out a season’s worth of subjects, from gun control to climate change. Stewart will tell you The Problem was born from “the same things that animated The Daily Show“; it’s just more “complete” and, to him, “more satisfying.” What it isn’t is laugh-out-loud funny, at least not in the way his Daily Show frequently was.

Episode one centers on veterans, a cause du jour of Stewart’s, with its focus on the millions being denied health care despite the devastating effects they’re facing from toxic exposure to burn pits. Per the new format, Stewart welcomes a panel of sufferers and their impassioned spouses to discuss the issue, then sits with the Secretary of Veterans Affairs to push for answers. Both Plepler and Stewart’s longtime agent, James “Babydoll” Dixon, who’s also a producer on the series, tell stories of the tears shed at the first taping. Even Stewart felt it necessary to acknowledge the relative earnestness during the inaugural show, at one point joking about the ribbing he’d get from his stand-up brethren the next time he sets foot inside the Comedy Cellar: “They’re all going to be like, ‘Ooh, look, Mother Teresa just came.’”

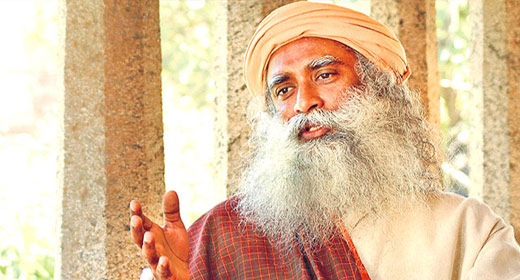

On an afternoon in late August, the 58-year-old New Yorker piped in from somewhere on Interstate 95 as he drove himself home from D.C., where he’d just sat with a high-ranking government official for the kind of on-location interview that was previously the territory of his Daily Show correspondents. In a wide-ranging conversation that stretched to two and a half hours, Stewart spoke candidly about his next act as well as his Daily Show departure, his HBO heartbreak and what he got wrong about Donald Trump.

Over the past six years, you’d emerge periodically and say how much you were enjoying your time out of the spotlight. When did that change?

Well, Lacey, it was an October night. The wind was howling off the water. A ship’s bells dinged in the distance. (Laughs.) No, it’s not as cut and dry as “I’m coming back” or “I’m not coming back.” It’s more, you make things. And I felt like the experiences that I’d had on The Daily Show combined with the experiences I’d had in D.C. enlightened me in a way that maybe I hadn’t been aware of previously. And it’s still just a TV show, but I was so struck by how the most seemingly obvious, simple things got derailed by the systems that are put in place to actually get them done. I’d been so taken by the people on the ground, putting in the manual labor to get incremental improvement in systems that are not designed for their input, and I thought, “Is there some way of exposing that?” Like, why is it so fucking hard? I guess the show could be called, “Why is it so fucking hard?”

I’m hoping you’ll give an example.

Yeah, you look at veterans’ [struggle to get proper] health care and benefits. My experience is with people who’ve been at this, at the expense of their entire livelihoods and mental health, and there’s a part of me that feels like, “I have one thing to offer, and that’s exposure. It’s the only thing I have.” And I’m not a young man. My career began on a show on MTV where I think the first character I introduced was called Butt Crack Guy. It was the one where we showed how the censors operated at MTV by how much butt crack on this one individual we could use. And that’s obviously a part of me, too, but you hope that your career is an ongoing evolution. I guess what I’m saying is, there will be moments of Butt Crack Guy in this, but I also like the idea of exposing these systems as a whole and trying to look at, like, “How the fuck is this system incentivized where there are so many people getting just jammed at the bottom of it?”

Sure.

Also, I’m really interested in that area that exists between rhetoric and reality. So, the first episode deals with service people, and everyone’s like, “Oh, we love our military.” Well, I don’t know if you’ve been paying attention, but they might not be feeling the love. And the second episode is about essential workers and the idea that they’re not the beneficiaries of any of the interventions. Honestly, it’s the same things that animated The Daily Show, we’re just adjusting the dials slightly. If The Daily Show was the weather report, I thought maybe it’d be interesting to do something that was [about] the climate. Now, one of the beautiful things about The Daily Show is that it was forgiving. When we shit the bed, there was always that, “Well, we’ll get it tomorrow.”

I suppose there’s less of that with a biweekly show.

That’s right. But also, in some ways, it can be more satisfying. I like that this is more of a conversation. It’s probably a terrible pitch for the show — “it’s The Daily Show, but less entertaining” — but also maybe more complete. And people will ask, “How are you going to live up to expectations?” Well, I’m not, and I never have. That’s not why we do it. We make things, and sometimes those things disappoint people and sometimes they really like them.

Have you always been able to maintain that perspective?

Early on, you ride a roller coaster, and you have no baseline of experience. My first nights in a club, if I killed, I was like, “I will sign that contract with NBC tomorrow for I am Robin Williams.” And then you’d have another night where you were like, “I will never open my mouth in public again. I will see if Panchito’s will take me back to the day shift.” You really have no understanding of what it means to be good, so the whole journey feels like an attempt to develop an authentic sensibility, a barometer to challenge yourself to do better work. And I’m always telling people at the show, like, “Get ready.”

What for, exactly?

They’re not accustomed to disappointment, and nothing turns to disappointment faster than love. And people fell in love a little bit with The Daily Show, but with that comes a lot of conflicting emotions about what you think I should be saying or doing, and how I should be doing it. And that’s all part of the ride. Sometimes it’s turbulent. Sometimes it’s welcoming. Sometimes it’s tongue baiting. But the ride itself is the thing that you construct, and you have to shut out the external expectation and pressure. You can’t make a show for people you don’t know.

I think that’s fair. I’m curious how you settled on the title. The show opens with a montage of possible titles, some clearly more absurd than others, before landing on The Problem With Jon Stewart. I liked The Money Grab With Jon Stewart, personally …

It really came down to The Issue With or The Problem With, and everyone thought one had a better swing to it. But one of the things I try to tell everybody at the show is, like, “We’re not going to use everything, but everything is going to help us get to a place that’s useful.” And that’s the thing with the title. It started out, like, “OK, people know me from The Daily Show, do we go Monthly? Do we do that? And what are we talking about with the show? It’s issues, but people are going to say this. Well, why don’t we call it Lower Your Expectations for Jon Stewart.” So, [the montage] is an ode to the creative process. And going back and forth with ideas is the part that I fucking love. The part where you put it out there and people go, “That’s fucking stupid,” or “Oh, you think you’re big now,” like, that’s not as fun.

I need to know, mostly on behalf of my copy desk, did you consider a comma after The Problem in The Problem With Jon Stewart?

Oh yeah, there’s a meeting about punctuation. We’re all talking about, like, “OK, well, what do you think about a comma?” It’s the thing that I love exposing with politics, which is, everything you see is an intention, somebody built it, somebody made a decision. Like, in the Iraq War, that whole, “We don’t want the smoking gun to be a mushroom cloud,” that came from a meeting. That was a PR guy, and they had meetings every week to talk about the best way to talk about going to war. And that same meeting is the one that we had to figure out what to call this fucking show. That’s what I love.

Talk to me about the hiring process with this show. I remember seeing your head writer, Chelsea, tweet about how applicants would be self-submitting their applications, which means they didn’t need Hollywood representation to apply.

Correct. And I’ve got to say, I was a little shocked with the results. Sometimes you have an intention and it’s theoretical and reality punches you in the face. But in this case, it created exactly what we were looking for, which is a varied staff, certainly varied perspectives and life experiences.

Having been in rooms that didn’t look like that in your past, how is the conversation different?

Those rooms exist to generate opinions and ideas, and when you have ideas and opinions that come from a cross section of perspectives, you get better quality materials; and if you have better materials, it’s naturally going to be stronger. And by the way, you also can’t over-process it because that’s not the reason we have those people. We have them because they’re great writers, and part of what makes them great writers is they write from their experience. In other words, they’re not charged with giving me the white soldier’s perspective or the Black female social work perspective, they’re charged with being good, interesting writers.

I think that’s fair.

(Sounding frustrated) You always say, “I think that’s fair.” It’s an interesting way of placing it. Like, I don’t feel like this show is exculpatory for my past. I’m not apologizing for what was. I don’t feel like I’m answering to anything, if that makes sense. I do feel like that’s the narrative and I understand it, but I just want to let you know I don’t agree with it.

Understood. The bio for your showrunner, Brinda, reads, “I’ve worked closely with anchors such as Diane Sawyer, David Muir, Scott Pelley, Norah O’Donnell and currently with Jon Stewart,” which seems like something The Daily Show‘s Jon Stewart would have had a really good joke for …

“Have you become what you lampoon?”

Exactly.

I don’t know, I hope not. But again, we’re back to an expectation … Like, Brinda is there because she’s fucking crazy smart and knows how to shape content. She’s not there to make me a newsman, because I’m not — but we don’t feel the need to define all that. And it bums me out, like, The Daily Show wasn’t about, “It sucks to be an anchor”; it was, “It sucks to be an anchor asking questions that don’t seem to be in any way connected to the people on the ground and the issues that they’re facing.” So I guess my perspective on it is, like, Brinda working with Diane Sawyer and now working with me doesn’t make me Diane Sawyer, or it doesn’t make me an establishment anchor. I’ve always been this way, and I think that the people who are around me view that narrative kind of cockeyed.

I did ask Brinda the same question, and she had a similar take with regard to these labels.

I guess my point is perception isn’t reality. But when, I think, [the media] industry is predicated on perception, it’s going in the wrong direction. It’s not really looking for what’s real, it’s looking for what’s noticeable. And I’m sure I took you aback there but I really think it does a disservice — and I know you’re in that business and you probably feel the frustrations of it, too, but can you see, on the outside, it is that idea of making things and all anybody wants to talk about is what they think are the salient news angles of it that aren’t actually about the thing.

Tell me, what is the thing that I asked that you’re reacting to? I understand your larger point but I’m a bit unclear on what set you off.

Here’s what I think it was: I was assuming that your outline came from places of controversy. That you viewed it as you were going to unwind the hiring. The title stuff felt like because Wyatt [Cenac] was upset about the title [he tweeted about its similarity to his since-canceled HBO series Problem Areas With Wyatt Cenac] and I felt like the hiring stuff was about the thing [Cenac was once the only Black writer on The Daily Show and, as such, he’s spoken publicly about his fraught relationship with Stewart and the show]. And it just felt like, “Oh, wow, this is interesting. It’s all controversies that don’t actually exist, but we’re going to pretend like we’re doing an interview about the reality of something when, really, we’re just going to deal with the reality created by a pretty narrow perspective.” It’s sort of like I went on the Today show once for a fundraiser for autism and I was on there with Michelle Smigel, who is Robert Smigel’s wife, and their son Daniel is autistic and really limited in the way he can communicate. And we were talking about a video that Michelle had showed me with Daniel completing a race, something they would’ve told you he’d never be able to, and the smile on his face was incredibly captivating. We shared that moment and we took a beat, and then the anchor, you might remember him, Matt Lauer …

Oh, I remember him.

He said to me, “Uh huh, interesting. You know, before you go, I have to ask you about Louis C.K.” And I think that’s what I’m reacting to. “Do you? Why?” And that’s my point here. Like, “I get what you have to do, it just feels kind of lousy.”

Here’s the truth: I cover this industry, I’ve heard about a lot of different efforts to change the system, and it’s a lot of lip service and press releases and, sure, there’s been some change, but not nearly enough. When I saw Chelsea’s tweet, I thought, this is interesting.

When we were talking about those things, and I’d answer, you would then say, “That’s fair.”

Yes, though I think that’s a verbal tic, more than anything else.

Oh, OK, then I apologize. What I thought you were saying is, “That’s a reasonable defense of your position.”

Well, clearly I need to stop saying “that’s fair.” I did notice in the premiere, you make a few jokes about the show not being hugely funny. Why do you think you do that?

It’s self-conscious. Look, I try to put in a process that keeps the speculation of people’s expectations out of the work but, as a person, you can’t help but be self-conscious. And as a comic, you’re always trying to read the room — the thing you learn is, if the glass breaks and you don’t say anything, you’re done. So, a lot of that is a self-conscious attempt to read the room and maybe take some of the steam out of it.

Ironically, the first piece of material to be released from this show was the “Dicks in Space” parody about Jeff Bezos heading to space.

Well, it’s also important for people to know that I’m still incredibly childish. (Laughs.)

It’s not particularly emblematic of what the show is, so I guess I’m curious about the decision to put that out first, and if you have any concerns that viewers will now come expecting more of that?

It’s not something we would have led with if Jeff Bezos had not been in a cowboy hat smiling from ear to ear having gone where many men have gone before. The egregiousness of the moment is what led us to want to release it when we did. We were like, “Let’s just fucking put it out there because we think it’s funny and maybe it’ll be a nice reminder that this [show] is coming.” But I never thought, “Oh God, now when we don’t deliver a short film every show, people are going to not know what they’re looking at.”

I meant more tonally …

On The Daily Show, we did a show with the 9/11 first responders and I also got a church choir to sing “Go Fuck Yourself.” I don’t know of a universe where shows are a monolith, and with this one we’re still finding our unique recipe. It could very much be an acquired taste, and that’s OK. It’s going to come out because it’s high profile, but hopefully enough people are interested in this way of looking at things.

I was about to say, “I think that’s fair” …

That’s hilarious. Now I feel badly I brought it up.

I’m glad you did. Speaking of perception versus reality, I hope you’ll indulge me because I want to tell you about two things I think I saw.

All right.

The first happened toward the end of your Daily Show run. I was on a flight back from Puerto Rico, and so were you and your family.

I remember that trip!

You were buried in a giant stack of magazines, and, from the outside, you looked just exhausted. Flash-forward to December 2018, and I’m in Hawaii with my family and, again, there you are with yours. Now, you were done with The Daily Show, and what I think I saw was a man who seemed free and happy.

It’s really interesting because there are probably pieces to what you’re saying that are accurate, but snapshots can be deceiving.

Which is exactly why I’m asking.

The truth is I left The Daily Show for a reason. It didn’t feel like I was singing as joyful a song as I wanted to be singing, but my life was still really good. I had wonderful moments at the show, and I didn’t feel it was a burden. I just didn’t know what else to do with it, this gift — and being allowed to be on TV is a gift. That said, I never felt the weight of the world at The Daily Show. I felt the weight of the team. I had this group of people who were industrious, talented, funny as fuck and raring to go, and my mind was wandering.

I’m glad I asked.

I’m more wondering where we’re going on vacation next. (Laughs.)

Somewhere amazing, I hope. As I said, I got a glimpse of you with your kids, who are now teenagers. How do they feel about their dad doing another TV show?

To them, The Daily Show was a circus. Like, there was a tension that surrounded their father, but not in a way that they could find tangible. Every now and again, they’d come to the show and I’d be doing some beautifully prepared essay on the hypocrisy of Fox Business or whatever it was and I’d just look over at them and they’d be dancing. (Laughs.) But they actually came to the first few shows for this, and I didn’t know what they’d think. My son Nate’s mind-set had always been, like, “Why don’t you do a show like Ellen? Then we can meet cool people.” So I was really, really delighted that they both walked away and were like, “Hmm, that was really interesting. Can we come to all of these?” Like, they expressed an interest in it for what it was, not just for it being a circus.

Your Daily Show follow-up was supposed to be a topical animation project for HBO. What happened?

The whole thing was predicated on the real-time animation thing. I think I got a little mad scientist-y with it, and I just didn’t crack it. The technology wasn’t quite there yet, but it was one of those things where I had this idea and it really lit me up. I was so excited, and then I remember looking at it and being like, “Oh right, in animation, they don’t look you in the eye. Oh boy, how am I going to fix that?” And in topical humor, there’s a turnaround time of, like, six hours, and animation is the most considered process in the world. I’m basically walking into Picasso’s office, going, “Hey man, you mind painting me something quick? My niece is coming in an hour.” So, you have those epiphanies sometimes where you’re like, “Oh, I was a fucking idiot.”

And nobody along the way is telling you it’s likely implausible?

I think people were feeling excited by the challenge. I mean, generally people love to crack a code. And you sweep them up in your enthusiasm and your vision, and when you’re not able to deliver, you feel not just that you disappoint them but like you’re fucking up their lives. It was really hard to let it go, but we reached a point where we were like, “OK, who has the job of taking Old Yeller out behind the barn?”

By not having a show on the air, you managed to miss the reign of Trump. I rewatched the Daily Show episode when he announced his candidacy, which was just before you signed off, and you were positively giddy. You called Trump a comedic “gift from heaven” …

What I missed there is that his certainty, his ridiculousness, his shamelessness is what made him dangerous. I thought it made him a buffoon, and I thought that’s what would disqualify him. What it did is made him the perfect vessel. You have to be shameless to do shameful things. I’m not saying he’s the same as these figures, but the most dangerous figures are the ones that seem comic and absurd. Saddam Hussein seems absurd. Muammar Gaddafi would stand in a kaftan and rant like a madman.

You recently joined Twitter, which had been Trump’s platform of choice …

Oh, it’s not for me.

OK, why not?

When you’re raised on a stand-up rhythm, there’s a show time and there’s an audience. It’s at 8 p.m. Your day is spent waiting for 8 p.m. And at 8 p.m., you go and you talk to the audience, and when you’re done, you leave. Twitter is an open mic that never shuts off. It’s like if the Cellar never shut down and the audience never left. And so the whole time you’re like, “Should I tell them something? Like, a joke?” I don’t know that I’ll ever feel comfortable with that. But you know what Twitter’s great for?

Tell me.

Telling you the thing that someone will never forgive you for. I almost view Twitter like I view Rotten Tomatoes. When the movie [2020’s Irresistible] came out, I’m not one of those guys who’s going to tell you, “Oh, I don’t read any of that,” of course I read it and I’m looking to see if the critics liked it, and they didn’t, for the most part, but you’re riding that score and feeling like it’s a reflection of the worth of what you do. Luckily, audience response was much more positive, and that made me feel better in that moment. But I feel like Twitter is Rotten Tomatoes for your soul.

Have you been surprised at all by the power of it? In March, you tweeted about your 2004 appearance on CNN’s Crossfire, in which you lampooned then-host Tucker Carlson, and suddenly the 17-year-old clip goes viral.

Oh, sure, it’s democratized connection and also democratized destruction. It’s like everything. Not to quote MC Hammer, but you can’t take the measure without considering the measurer. It’s kind of the point I was making on Colbert that everybody got mad about, which was, “These are just tools, we’re the ones that fuck them up.” So yeah, it’s exciting and connecting and incredibly dangerous, like pretty much everything we’ve ever made.

You’re referencing your June appearance on The Late Show where you went all in on the theory that the coronavirus originated from a lab in China. I couldn’t tell if Colbert was entertained by your bit or maybe a little nervous.

I don’t think he was nervous. It’s not like he doesn’t know what I’m going to say. Listen, how it got to be that if it was a scientific accident, it’s conservative, and if it came from a wet market, it’s liberal, I don’t know — I’m just not sure how that got politicized. But it was an inelegant way to get to a bit that I’ve done for years, which is our good-intentioned brilliance will more than likely be our demise. The bit is about the last words that man ever utters, which are, “Hey, it worked.” I guess I was a little surprised at the pushback.

You mentioned films. Curious, what itch does moviemaking scratch for you that perhaps this or The Daily Show do not?

Say you like to cook. Sometimes you like to cook a quiet meal for a couple of people; sometimes you get a hankering to do a little short-order work — slap out some pancakes and eggs and feel that pressure of running around the kitchen. And sometimes you may want to try that slow-cooked Tuscan experience, where you put out the long wooden table, and that’s sort of what this is. Or to put it in old Jew, we’re making pickles. Sometimes we brine them for a day, but you get a different flavor if you age it. Moviemaking is a very different, considered process, but it’s still the same form.

Do you have more movies in you?

I hope there’ll be more. I love doing it. But I also had that feeling in an Ohio cornfield with Dave Chappelle, just sitting there doing a show for 300 people in masks. I hope I get to do more of that, too. I hope I get to do more of all of it. You don’t get that many chances in life to get lit up by something. It’s like I took up the drums when I left The Daily Show, and learning limb independence and different rhythms and interacting with music in a way that I’d always wanted to but never could is almost like the opposite of death. I just fucking love that feeling.

I can hear it in your voice.

I know it’s fucking corny, and I know it’s probably like talking to an old guy that’s starting to move into the back … I was going to say back nine, but that’s probably too generous. Back three? Back four? I don’t know where I am on the course. Getting closer to hitting up a drink on the 19th hole? But I can remember working as a day bartender at Panchito’s, a Mexican restaurant on MacDougal Street, and the day bartender is the shit job at a Mexican restaurant. You spend your entire day making margarita mix and cutting fruit so that the night bartender can clean up, and you make nothing because no one is there at lunch. But I got a good meal out of it, and it allowed me to go down the street to the Cellar and hang there all night. And I made no money, and when I say I had a roommate, I mean, he lived in the room with me and I wasn’t a college kid. I must’ve been 26, 27 years old, and I just remember walking home from the Village at 3 or 4 in the morning, and I was filled with this feeling of fucking peace and pride and joy. It’s not a feeling I’m accustomed to, and there were moments on the set in Jordan [making his first movie, Rosewater], where I had that feeling, too. But when people ask me, “When did you feel you made it?” I think I knew the minute I had that feeling walking home in the Village. It didn’t really matter what happened after.