by Margaret Eby: One woman goes deep in an exploration of her favorite fall fungi…

If you’ve picked up a cellophane-wrapped punnet of mushrooms from a grocery store sometime in the past couple of decades, odds are high that you’ve tasted the output of Kennett Square, a small town in southeastern Pennsylvania.

From 2019 to 2020, Pennsylvania sold 526,336,000 pounds of mushrooms, about two-thirds of the total amount of mushrooms sold in the United States, and the majority of that production was in Chester County, the area around Kennett Square. The town has a mushroom painted on its water tower, an annual mushroom festival, and a gift shop called The Mushroom Cap, where enthusiasts can purchase all manner of mushroom paraphernalia, including handmade mushroom-cleaning brushes and socks that read “Shiitake happens.” Which is how, on an unexpectedly hot day in March, I found myself at Laurel Valley Farms in Chester County, on a roof overlooking a vast, fragrant field of compost. This is where mushrooms are born.

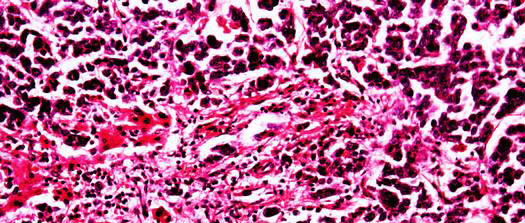

The first thing you should know about farmed mushrooms is that they do not grow in what is politely termed “excrement.” In fact, mushrooms grow in what is called substrate—a carefully formulated, pasteurized compost mixture (which might include excrement as an ingredient). Unlike plants, fungi cannot photosynthesize and must get their nutrients from the material they grow in, so this substrate mixture is incredibly important. Each mushroom farm has its own substrate formula and its own regulations for how it is mixed and then inoculated with mushroom spawn that later, thanks to manipulations of humidity and temperature, will fruit into the fungi that get packed up and shipped off to supermarkets around the country.

Covering the mushrooms for the first few minutes helps them release their liquid and brown more quickly. Versatile and umami-rich, these mushrooms can be served as a side dish; they could also be spooned over steak, or stirred into hot pasta for an easy dinner.

Get the Recipe: Buttery Sautéed Mushrooms with Fresh Herbs

Laurel Valley, the largest mushroom composting facility in the United States, is a co-op, owned by five of the major mushroom farms in the area. Jim Angelucci, the general manager of Phillips Mushroom Farms, one of Laurel Valley’s co-owners, was giving me a tour of the operations, pointing out various elements of the substrate as the fumes wafted up from the afternoon sun hitting 58 acres of compost. The piles in the distance, Angelucci said, were a combination of cobs, poultry litter, mulch hay, stable bedding, wheat straw, gypsum, and cacao shells from nearby Hershey. “It gives the compost a chocolaty aroma,” Angelucci joked. After being mixed, pasteurized, and optimized for temperature and pH level, the compost is inoculated with each farm’s proprietary mycelium spawn supplement—the fungal culture that mushrooms grow from—and distributed to the farms’ growing facilities to continue the life cycle. Laurel Valley produces about 3,700 to 3,900 tons of inoculated compost every week.

“The quality of mushrooms depends on three things,” Angelucci told me. “The genus, the quality of the substrate, and the art of the grower.” That art was on full display at Phillips, a fourth-generation mushroom farm that sells more than 57 million pounds of mushrooms a year. The most popular mushroom they grow, by far, is the white button mushroom, followed by what Angelucci calls “browns”—cremini and portobellos; the latter two are the same mushroom, picked at different points in their maturation. All three grow in the same environment—long, squat, dimly lit white warehouses lined with towers of compost beds. The beds are 5 1/2 feet wide and 60 feet long, stacked six high and 24 across, and they look like vats of crumbled Oreos until you get close enough to see the bulbous heads of mushrooms emerging from the dark, peat moss–scattered substrate, like tangled strings of tiny, opaque light bulbs.

Feathery and dramatic, hen-of-the-woods mushrooms (also known as maitake) become delightfully crispy when fried. You know they are nearly ready when the sizzling oil starts to subside. Here, prepared marinara and freshly grated Parmigiano-Reggiano cheese gives these crispy mushrooms Italian-American flair.

Get the Recipe: Crispy Hen-of-the-Woods Mushrooms with Marinara and Parmigiano-Reggiano

Phillips is also the largest grower of specialty mushrooms such as hen-of-the-woods, shiitake, lion’s mane, king trumpet, and oyster mushrooms. Angelucci took me around the warehouses to see their different growing arrangements—the shiitakes poking out of artificial logs; the gerbil-like lion’s manes puffing their fuzzy heads out of substrate-filled plastic bags; the blue, yellow, and gray oyster mushrooms emerging from a tower of substrate like alien saguaro cacti. Though these mushrooms represent a small slice of the farm’s business, dwarfed by the volume of white and brown mushrooms, consumer interest in them has ticked up in the past few years—part of a broad embrace of all things mycological. (In addition to a culinary ‘shroom boom, interest in medicinal and functional mushrooms for health and well-being has also skyrocketed.) “These mushrooms have always been around, so as demand for mushrooms in general has grown, so has interest in these varieties,” explained Eric Davis of the Mushroom Council. “The boats are rising equally—it’s not like shiitakes are overtaking white buttons the way Honeycrisp apples overtook Red Delicious.” (For a guide to farmed specialty mushrooms, see “Glossary of Mushrooms“)

“To me, mushrooms are about texture,” said James Wayman, the chef-owner of Grass & Bone and Nana’s Bakery & Pizza in Mystic, Connecticut, who cooks with both farmed and foraged mushrooms. “What’s the texture going to be once they’re cooked? The more common buttons, portobellos, cremini—they’re more watery. Shiitakes are going to be denser, so they work really well in soup. You think about what cooking methods would be appropriate.” Farmed mushrooms tend to be more delicate in flavor than their wild counterparts, Wayman explained. When approaching a variety he’s unfamiliar with, he usually goes for a fail-safe method—frying the mushrooms in butter and a bit of olive oil, adding garlic and parsley, and hitting them with a splash of acid, like sherry vinegar, at the end. “You can use that method with anything; it’s very versatile.”

Thick-stemmed king trumpet mushrooms grill up meaty and tender, while feathery oyster mushrooms get nice and crispy— both are great options for these quick- cooking kebabs. Piled into warm pitas with a smear of tangy labneh and a drizzle of intensely herby salsa verde, this dish is a fun, fresh way to enjoy mushrooms.

Get the Recipe: Smoky Mushroom Skewers with Labneh and Salsa Verde

I even grew a new appreciation for humble white button mushrooms.

When I left Phillips Mushroom Farms, I took along with me, at a conservative guess, about 20 pounds of freshly harvested mushrooms, a case each of their specialty varieties secured in the back seat with a seat belt. Over the next week, I fried, sautéed, grilled, roasted, and pulverized them in various combinations to try to get a sense of their textural elements. I found that hen-of-the-woods mushrooms, also known as maitake, are excellent roasted or grilled whole. The leaf-like tendrils crisp up like the outer leaves of brussels sprouts, and the base becomes tender and meaty, a perfect vehicle for sauce. (See the Crispy Hen-of-the-Woods Mushrooms with Marinara and Parmigiano-Reggiano recipe) The lion’s mane mushrooms were best sliced and sautéed, which enhanced their delicate, slightly stringy interior, similar to the meat in a crab claw. Oyster mushrooms, chewier, with a texture almost like chicken, stood up well to the grill and made an excellent addition to pasta or rice. I even grew a new appreciation for humble white button mushrooms, which I ate raw, savoring their mild creaminess and the slight squeak they produce when you bite down on them, the way cheese curds do.

Though most of the farmed mushrooms available in the United States come from large operations like Phillips, there’s a constellation of smaller growers that sell to farmers markets. Mushroom farming requires a controlled environment and fungus know-how, but the bar for entry can be quite low, as William Padilla-Brown, self-taught mushroom grower, citizen scientist, and entrepreneur, can tell you. Padilla-Brown became fascinated with mushrooms as a teenager. “I wanted to know where things were coming from. Around that time, I was a vegetarian, and I wanted to eat more protein-rich foods,” Padilla-Brown explained. “I tried to seek out people who were able to teach me how I could grow them. There wasn’t really anybody around me to teach me, so I did a bunch of research and started playing around with cultivating them at home.”

Make-ahead mushroom duxelles make a rich filling for these tender, satisfying dumplings. The broth, infused with toasted ginger and garlic, gets an extra layer of rich mushroom flavor from dried white flower shiitake mushrooms, which have a bolder flavor than regular dried shiitakes, which are a fine substitute.

Get the Recipe: Mushroom Dumplings in Toasted Ginger and Garlic Broth

At 18, Padilla-Brown grew his first oyster mushroom in an environment he cobbled together using coffee grounds and cardboard in a plastic sandwich bag. Those initial experiments grew into MycoSymbiotics, the ecological-research company where Padilla-Brown grows and studies several less widely known kinds of medicinal and culinary mushrooms, which he sells at local markets. He also runs an annual mushroom festival and has written two books on his discoveries cultivating the Cordyceps mushroom, a typically vivid orange variety that looks like the mushroom version of a Cheeto. He’s something of a mushroom influencer, and he’s never stopped expanding his knowledge on the subject.

“I’m trying to get to the point where I can understand the terroir in mushrooms,” Padilla-Brown said. “When you first get into it, it’s all ‘earthy’ until you’re able to describe the subtle notes in them, and your palate learns.”

Mushroom farming isn’t just a business—it’s a potentially revolutionary act.

When he went to farmers markets with his crop, Padilla-Brown ran into customers who were confused about the oyster, lion’s mane, and Cordyceps mushrooms he sold, which didn’t look like the standard white buttons. He used it as an opportunity to educate people. “Mycophobia is a really common thing,” Padilla-Brown said. “People think that because they didn’t like the mushrooms they ate on pizza when they were little, all mushrooms are gross. But there are so many textures and flavors in mushrooms.”

Marinated in a blend of Champagne vine- gar, olive oil, toasted fennel seeds, garlic, and thyme, these tender mushrooms are a winning appetizer waiting to happen. Spoon them over ricotta-topped toast or gooey baked Brie, or add them to a cheese board with plenty of crusty bread for sopping.

Get the Recipe: Mushroom Conserva

To Padilla-Brown, mushroom farming isn’t just a business—it’s a potentially revolutionary act. His focus is on making mushroom cultivation more accessible to everyone, but particularly to communities of color, encouraging the creation of what he calls ecologically regenerative sustainable micro-industries. Part of his mission is sharing the knowledge behind mushroom growing for future DIY mycologists in the hopes that farmed mushrooms could be a way to combat food apartheid. At MycoSymbiotics, he sells the materials to grow Cordyceps mushrooms. He hosts talks and workshops on getting into mushroom farming and foraging, and he has an audience on YouTube and Instagram, where he explains his methods and points to low-tech, low-cost solutions for common cultivation problems. If you want to grow mushrooms, no matter your space or budgetary constraints, Padilla-Brown has advice.

“It doesn’t take millions of dollars of investment and venture capital to start. As soon as you start to play with mushrooms, you realize you can do it, too,” Padilla-Brown said. “I’m a young Black kid, a high school dropout. I was supposed to fail; there wasn’t a model for me. That I’m living a successful life, and am able to feed my kid, I think that’s the power of mushrooms, too.”

Mushrooms love wine. Their lack of the compounds found in some vegetables—the sharp sulfur compounds of cruciferous veggies, the palate-distorting cynar in of artichokes—means that, at the very least, they’re friendly to almost every wine. (Yes, fungi aren’t technically vegetables, but a mushroom is way closer to a potato than it is to a cow.) And for some wines, mushrooms’ savory earthiness highlights those same notes; it’s like being in an echo chamber of umami.

Older Pinot Noirs, earthy and autumnal, are stellar choices for mushroom dishes. So, too, is aged Rioja, with its aromas and flavors of dried cherries and leather. But most of us don’t have wine cellars. Happily, Chi- antis, like the 2018 Castello di Volpaia Chianti Classico ($22), with its currant-cherry and forest floor character, work beautifully with dishes like Crispy Hen-of-the-Woods Mushrooms with Marinara and Parmigiano-Reggiano. Peppery Syrahs also complement mushrooms beautifully—try king trumpet and oyster mushrooms, skewered and served with salsa verde, with a Rhône Crozes-Hermitage like the 2018 Delas Les Launes Rouge ($28). Spain’s sparkling Cavas lean naturally toward earthy notes; try the nonvintage Segura Viudas Brut Reserva Heredad ($22) with our mushroom dumplings in a dried shiitake broth. Finally, fans of natural reds—many of which show savory, even funky notes— should look for Loire wines like the 2018 Pierre-Olivier Bonhomme Le Telquel ($22), a great choice for cheesy dishes like mushroom conserva over toast with ricotta. —Ray Isle