by Kimiya Shokoohi: From ancient Egypt to the Persian Empire, an ingenious method of catching the breeze kept people cool for millennia. In the search for emissions-free cooling, the “wind catcher” could once again come to our aid…

The city of Yazd in the desert of central Iran has long been a focal point for creative ingenuity. Yazd is home to a system of ancient engineering marvels that include an underground refrigeration structure called yakhchāl, an underground irrigation system called qanats, and even a network of couriers called pirradaziš that predate postal services in the US by more than 2,000 years.

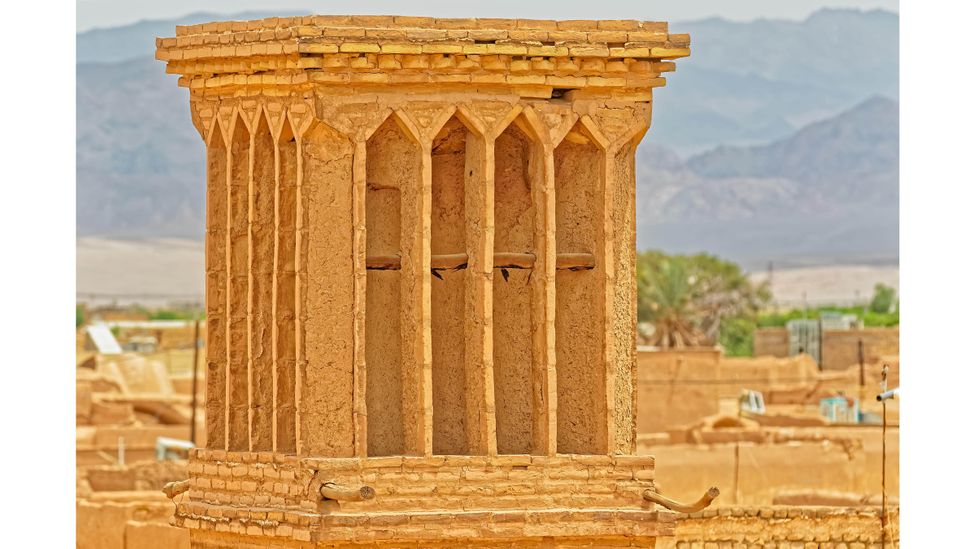

Among Yazd’s ancient technologies is the wind catcher, or bâdgir in Persian. These remarkable structures are a common sight soaring above the rooftops of Yazd. They are often rectangular towers, but they also appear in circular, square, octagonal and other ornate shapes.

Yazd is said to have the most wind catchers in the world, though they may have originated in ancient Egypt. In Yazd, the wind catcher soon proved indispensable, making this part of the hot and arid Iranian Plateau livable.

Though many of the city’s wind catchers have fallen out of use, the structures are now drawing academics, architects and engineers back to the desert city to see what role they could play in keeping us cool in a rapidly heating world.

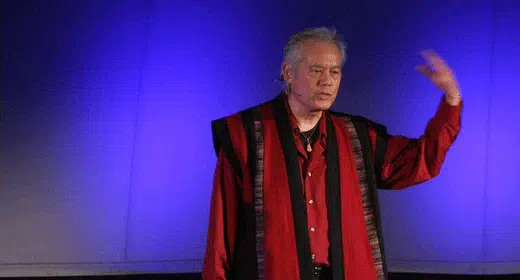

The openings of the towers face the prevailing wind, catching it and funneling it down to the interior below (Credit: Alamy)

As a wind catcher requires no electricity to power it, it is both a cost-efficient and green form of cooling. With conventional mechanical air conditioning already accounting for a fifth of total electricity consumption globally, ancient alternatives like the wind catcher are becoming an increasingly appealing option.

There are two main forces that drive the air through and down into the structures: the incoming wind and the change in buoyancy of air depending on temperature – with warmer air tending to rise above cooler, denser air. First, as air is caught by the opening of a wind catcher, it is funneled down to the dwelling below, depositing any sand or debris at the foot of the tower. Then the air flows throughout the interior of the building, sometimes over subterranean pools of water for further cooling. Eventually, warmed air will rise and leave the building through another tower or opening, aided by the pressure within the building.

The shape of the tower, alongside factors like the layout of the house, the direction the tower is facing, how many openings it has, its configuration of fixed internal blades, canals and height are all finely tuned to improve the tower’s ability to draw wind down into the dwellings below.

Some of the earliest wind-catching technology comes from Egypt 3,300 years ago

Using the wind to cool buildings has a history stretching back almost as long as people have lived in hot desert environments. Some of the earliest wind-catching technology comes from Egypt 3,300 years ago, according to researchers Chris Soelberg and Julie Rich of Weber State University in Utah. Here, buildings had thick walls, few windows facing the Sun, openings to take in air on the side of prevailing winds and an exit vent on the other side – known in Arabic as malqaf architecture. Though some argue that the birthplace of the wind catcher was Iran itself.

Wherever it was first invented, wind catchers have since become widespread across the Middle East and North Africa. Variations of Iran’s wind catchers can be found in the barjeels of Qatar and Bahrain, the malqaf of Egypt, the mungh of Pakistan, and many other places, notes Fatemeh Jomehzadeh of the University of Technology Malaysia and colleagues.

Due to long disuse, many of Iran’s windcatchers are not in a good state of repair. But some researchers would like to see them restored to working order (Credit: Alamy)

The Persian civilisation is widely considered to have added structural variations to allow for better cooling – such as combining it with its existing irrigation system to help to cool the air down before releasing it throughout the home. In Yazd’s hot, dry climate, these structures proved remarkably popular, until the city became a hotspot of soaring ornate towers seeking the desert wind. The historical city of Yazd was recognised as a Unesco World Heritage site in 2017, in part for its proliferation of wind catchers.

As well as performing the functional purpose of cooling homes, the towers also had a strong cultural significance. In Yazd, the wind catchers are as much a part of the skyline as the Zoroastrian Fire Temple and Tower of Silence. Among them is the wind catcher at the Dowlatabad Abad Gardens, said to be the tallest in the world at 33m (108ft) and one of the few wind catchers still in operation. Housed in an octagonal building, it overlooks a fountain stretching past rows of pine trees.

Inconveniences like pests entering the chutes and the gathering of dust and desert debris have meant many have turned away from traditional wind catchers

The emissions-free cooling efficacy of such wind catchers make some researchers argue that they are due a revival.

Parham Kheirkhah Sangdeh has extensively studied the scientific application and surrounding culture of wind catchers in contemporary architecture at Ilam University in Iran. He says inconveniences like pests entering the chutes and the gathering of dust and desert debris have meant many have turned away from traditional wind catchers. In their place are mechanical cooling systems, such as conventional air-conditioning units. Often, those options are powered by fossil fuels and use refrigerants that act as powerful greenhouse gases if released into the atmosphere.

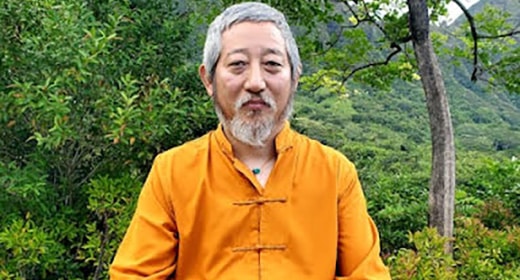

The wind catchers of Iran have inspired modern designs in Europe, the US and elsewhere, as architects turn towards passive forms of cooling (Credit: Alamy)

The advent of modern cooling technologies has long been blamed for the deterioration of traditional methods in Iran, the historian of Iranian architecture Elizabeth Beazley wrote in 1977. Without constant maintenance, the harsh climate of the Iranian Plateau has worn away many structures from wind catchers to ice houses. Kheirkhah Sangdeh also sees the shift away from wind catchers as in part down to a tendency among the public to engage with technologies from the West.

“There needs to be some changes in cultural perspectives to use these technologies. People need to keep an eye on the past and understand why energy conservation is important,” Kheirkhah Sangdeh says. “It starts with recognising cultural history and the importance of energy conservation.”

Kheirkhah Sangdeh hopes to see Iran’s wind catchers updated to add energy-efficient cooling to existing buildings. But he has met many barriers to his work in the form of ongoing international tensions, the coronavirus pandemic and ongoing water shortage. “Things are so bad in Iran that [people] take it day by day,” says Kheirkhah Sangdeh.

Yazd is said to have the most wind catchers of any city in the world (Credit: Alamy)

Fossil-fuel-free methods of cooling like the wind catcher might well be due a revival, but to a surprising extent they are already present – albeit in a less magnificent form than those in Iran – in many Western countries.

In the UK, some 7,000 variations of wind catchers were installed in public buildings between 1979 and 1994. They can be seen from buildings such as the Royal Chelsea Hospital in London, to supermarkets in Manchester.

These modernised wind catchers bear little resemblance to Iran’s towering structures. On one three-storey building on a busy road in north London, small hot pink ventilation towers allow passive ventilation. Atop a shopping centre in Dartford, conical ventilation towers rotate to catch the breeze with the help of a rear wing that keeps the tower facing the prevailing wind.

The US too has adopted wind-catcher-inspired designs with enthusiasm. One such example is the visitor center at Zion National Park in southern Utah. The park sits in a high desert plateau, comparable to Yazd in climate and topography, and the use of passive cooling technologies including the wind catcher nearly eliminated the need for mechanical air-conditioning. Scientists have recorded a temperature difference of 16C (29F) between the outside and inside of the visitor centre, despite the many bodies regularly passing through.

There is further scope for the spread of the wind catcher, as the search for sustainable solutions to overheating continues. In Palermo, Sicily, researchers have found that the climate and prevailing wind conditions make it a ripe location for a version of the Iranian wind catcher. This October, meanwhile, the wind catcher is set to have a high-profile position at the World Expo fair in Dubai, as part of a network of conical buildings in the Austrian pavilion, where the Austrian architecture firm Querkraft has taken inspiration from the Arabic barjeel version of the wind tower.

While researchers such as Kheirkhah Sangdeh argue that the wind catcher has much more to give in cooling homes without fossil fuels, this ingenious technology has already migrated further around the world than you might think. Next time you see a tall vented tower on top of a supermarket, high-rise or school, look carefully – you might just be looking at the legacy of the magnificent wind catchers of Iran.