Nearly all experts agree that we should eat less salt. But opposition from the food industry and a handful of scientists has stalled efforts to cut the salt in the two biggest sources: packaged and restaurant foods…

Salt 101

Q: Why do you call salt the biggest killer in our diets?

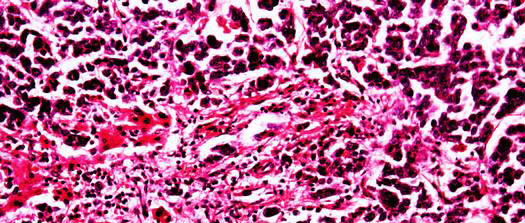

A: Salt raises blood pressure, and high blood pressure—or hypertension—increases the risk of heart attacks and strokes, two major killers in our society. Hypertension also increases the risk of chronic kidney disease, impaired memory and vision, and erectile dysfunction.

If you don’t have hypertension now, odds are that someday, you will. Roughly 80 to 90 percent of Americans eventually develop high blood pressure as they get older.

The high-salt diet that Americans are eating is responsible for an estimated 100,000 premature deaths every year and roughly $20 billion in healthcare costs. It’s just an enormous health toll.

Q: Can’t people just take drugs to lower their pressure?

A: Drugs can be very effective in lowering blood pressure and the risk of heart attacks and strokes, but they’re hardly the perfect answer. Many people stop taking the drugs over time because of the expense or because they don’t feel any effect.

And one drug may not work, so you have to take two or three, and even that may not work. Drugs can also have side effects like disturbed sleep, headache, muscle cramps, an increased need to urinate, and erectile dysfunction.

So why not just try to keep your blood pressure low so you can avoid the side effects and the costs and the visits to doctors.

Q: How much salt do we eat?

A: The average woman consumes about 3,000 milligrams a day, and the average man about 4,000 milligrams a day, mostly because men eat more food. Only about 2 percent of men and 20 percent of women consume less than the recommended 2,300 milligrams per day.

Q: And the salt shaker isn’t the key culprit?

A: No. We get only 5 percent of our salt from the shaker, and another 5 percent or so from the salt we add when we cook at home. And about 15 percent occurs naturally in foods.

Roughly 70 percent comes from the salt and other food additives like monosodium glutamate that are added to processed and restaurant foods.

Q: Which foods are the biggest culprits?

A: Salt is everywhere. It’s in processed meats like bacon and cold cuts, frozen dinners, soups, pizza, sandwiches. Breads and rolls supply more sodium than any other food category—in part because we eat them so often—but they supply only 6 percent of the salt we eat.

The foods that are highest in salt are restaurant meals. Some contain two or even three times as much sodium as somebody should eat in an entire day.

New York City and Philadelphia now require menus at chain restaurants to put warnings next to items that contain an entire day’s worth of sodium or more.

Q: So it’s not just salty-tasting foods?

A: Right. Nobody thinks bread tastes salty, but at Panera, the piece of baguette that comes on the side has nearly six times as much sodium as the chips. So you can’t go by taste. You have to read labels. And restaurant foods don’t come with sodium labels, though many chain restaurants post the numbers online.

Q: So what should people do?

A: You can eat a healthy diet with lots of fresh fruits and vegetables, beans, nuts, low-fat yogurt or milk, fish, and poultry, rather than processed foods. That will not only lower your sodium intake but also boost your potassium intake.

Potassium has long been known to lower blood pressure in people with hypertension. So replacing sodium with potassium could be a win-win. When cooking, I routinely use a lite salt, which is half sodium chloride and half potassium chloride.

Just check with your doctor before you use potassium salts if you have kidney disease or heart failure, or if you take drugs like ACE inhibitors, angiotensin II receptor blockers, or potassium-sparing diuretics.

The science war

Q: What do you mean by Salt Wars?

A: One war is the battle over the scientific evidence. The other is over what government and industry should do about salt.

Q: Isn’t the science settled by now?

A: It’s settled to most scientists and to health authorities like the National Academy of Medicine, the World Health Organization, and the American Heart Association. They recommend that we consume about a third less sodium.

But a few vocal scientists argue that consuming less salt would be dangerous.

Q: What do they contend?

A: Their studies find a higher risk of heart attacks and strokes not only in people who consume excess sodium—say, 5,000 milligrams a day—but also in those who consume below-average levels—around 2,000 milligrams.

On the surface, some of those studies appear persuasive. For example, the PURE study looked at 100,000 people worldwide.

But the studies are misleading.

Q: How?

A: As in any observational study—which simply measures an exposure like sodium and then sees what happens to people over time—something else about the participants may explain their higher risk of disease. For example, some people who consume less sodium may be eating less food because they’re ill or because they don’t have enough food.

Q: And illness or poverty could explain their higher risk?

A: Right. But the most serious flaw is that those studies didn’t accurately measure how much sodium people typically consume.

The only reliable way to estimate someone’s long-term sodium intake is to have them collect all of their urine for 24 hours on several days.

But the PURE researchers estimated each participant’s sodium intake with only one “spot” urine collection—meaning that each person urinated into a container just once—at the beginning of the study. Then the researchers used a mathematical formula to estimate 24-hour sodium intakes.

Q: And that’s inaccurate?

A: Yes. When a different team of scientists measured sodium with repeated 24-hour urine collections, they found that people who consumed the least sodium had no higher risk of dying over the next 24 years.

But then the scientists used PURE’s formula to estimate the long-term sodium intakes of the same people. Sure enough, they found a higher risk in people who, according to the formula, consumed the least sodium.

That’s really good evidence that PURE and similar studies were fatally flawed. When a National Academy of Medicine panel looked at those studies in 2019, it concluded that they were unreliable.

Q: Those studies got huge headlines.

A: Journalists love man-bites-dog stories. We also saw that about 10 years ago when newspaper headlines declared that low-salt diets might be dangerous.

That was largely based on Italian studies on patients with severe congestive heart failure. Those who were put on a low-sodium, fluid-restricted diet were more likely to die. But they also got high doses of a powerful diuretic—an unwise treatment.

Q: Most media didn’t mention that?

A: No. The American Heart Association said that the results in such a sick and highly medicated group had no relevance for most people, or even for most patients with heart failure.

To put the nail in the coffin, a few years later, a meta-analysis of the Italian studies was retracted. When the journal asked the researchers to supply the raw data from some of the studies, they said that it had been lost in a computer failure. It was essentially a dog-ate-my-homework excuse or an inexcusable failure to properly store data.

Still, those headlines got so much attention that they set back the cause of reducing sodium for years.

Q: Any chance that the science war will end?

A: In 2019, the National Academy of Medicine may have put the matter to rest. An expert panel combined the results of several randomized controlled trials on sodium and cardiovascular disease. And the experts found a lower risk in people who ate less sodium.

I haven’t seen much argument since that report was published.

The industry war

Q: What about the second salt war?

A: The processed-food and restaurant industries have fought for decades to continue using as much salt as always, just as industry fought for years to keep using trans fat until it was banned.

Q: And the government?

A: In response to four decades of countless preventable deaths and government inaction, in 2010, a report by the Institute of Medicine, which is now the National Academy of Medicine, urged the Food and Drug Administration to set mandatory limits on the sodium content of different food categories—potato chips, canned soups, pizza, and so on—and to gradually lower those limits over time.

So in 2016, the FDA proposed sodium targets for both packaged and restaurant foods, though they were only voluntary.

Q: Did the industry object?

A: At first. The Grocery Manufacturers Association, which was the most influential food industry trade group, said yes, it could be useful for Americans to lower sodium, but then came up with 100 reasons why sodium should not be lowered. The Salt Institute, the association of manufacturers like Morton Salt, just urged the FDA to abandon the targets.

Q: And now?

A: In the last few years, several major companies—like Unilever, Nestlé, and Mars—have declared their support for the FDA’s voluntary targets. The Grocery Manufacturers Association lost several major food companies and morphed into the Consumer Brands Association. And, thankfully, the Salt Institute has gone out of business. So the political landscape has changed dramatically.

However, here we are four years later, and the FDA has not done a darn thing to finalize the targets.

Q: How do we know that companies can cut sodium?

A: If you compare different brands of almost any food—salad dressings, breads, packaged meats, pasta sauces—you’ll find wide disparities in sodium content.

That proves that many companies could lower the sodium levels to match the best performers in each category.

Also, some foods sold at McDonald’s, Burger King, and other chain restaurants in other countries have less salt than the same foods sold here.

Q: Why?

A: Many countries have made more progress than we have. The United Kingdom led the way. About 15 years ago, it set voluntary sodium targets, pressured food manufacturers to lower sodium, and mounted a campaign urging people to eat less salt.

After five years, sodium intakes fell by around 10 percent, which was about a quarter of the program’s goal. But when there was a change in government, progress came to a halt.

Q: Are there other approaches?

A: Yes. Chile, Israel, Uruguay, and other countries have been very effective with food labeling. Foods with more than specified levels of sodium have “high in salt” warnings on the front of the package.

Similar symbols highlight foods high in saturated fat or sugar. A food could have two or three warning symbols.

After a couple of years, Chile lowered its threshold for a sodium symbol, and then dropped the threshold even further. That’s what we need to do here.

Q: After 40 years of fighting the salt wars, where do we stand?

A: If we go back 40 years, when you and I wrote a petition asking the FDA to require food labels to disclose sodium, we had support from many scientists and expert committees that said that Americans should eat less sodium.

But since then, increasingly sophisticated research has demonstrated beyond a shadow of a doubt that we would benefit tremendously by eating lower-sodium diets.

Q: Yet the progress has been slow.

A: Yes. Despite the plethora of petitions, lawsuits, books, TV interviews, and meetings, the government and the food industry have failed to act. Americans are still consuming roughly 50 percent more sodium than experts recommend—and are suffering the consequences. The industry war is essentially a stalemate.

Salt savings

You’d never know that some foods have less sodium without checking the Nutrition Facts label. One clue: Foods labeled “healthy” often have less. Even restaurant foods in the “Lower” column are loaded with sodium.

How to lower your pressure

Got high blood pressure? Here’s how much your systolic pressure could fall with diet and exercise. If you don’t, expect a drop of 2 to 4 points for each step.

To find out how many servings of different foods are in the DASH diet, check out this post.