by Morgan Meis: While working as an independent archeologist, an Indonesian grad student revised the human story…

Basran Burhan was born in Indonesia, on the centrally located island of Sulawesi. He studied archeology at Hasanuddin University, at first, he told me, mostly because he liked how it involved “a lot of outdoor activities.” After graduating, in 2010, he worked for a few different Indonesian research and cultural heritage institutions. He also became an independent archeologist, helping organize excavations for a researcher named Adam Brumm at Griffith University, in Australia. Burhan’s field work struck Brumm as exceptional, and on the strength of it Brumm tried to get Burhan into a Ph.D. program. But Burhan’s imperfect English delayed this project for a number of years. Instead, he kept working for Brumm and his team.

In 2017, Burhan was helping Brumm and other researchers plan their next season of fieldwork: searching for evidence of Paleolithic humans in Sulawesi. Earlier that year, Brumm had briefly explored a new area on the island that seemed promising. Burhan and a team of six Indonesian archeologists were sent there on a field exploration.

The survey lasted for several weeks. At some point, poring over a map of the island’s southern region, Burhan found his eyes drawn to an area he’d never noticed, let alone visited—a valley in a mountain region twenty miles or so northeast of the city of Makassar. There were no roads into the valley, and there was nothing on the map to suggest a way through the bush and mountain peaks. The map did indicate rice paddies and other signs of human habitation, but Burhan didn’t know if the area was currently populated. A good part of archeology is simply exploration. Burhan thought, Why not?

Burhan and his team asked for directions from whomever they encountered, and continually got lost. But eventually they found a path through a cave that led into the hidden valley. The area was inhabited by an especially isolated group of Bugis people, an ethnic group of southern Sulawesi who recognizes five separate genders. The Bugis claimed never to have seen a single Westerner in their valley.

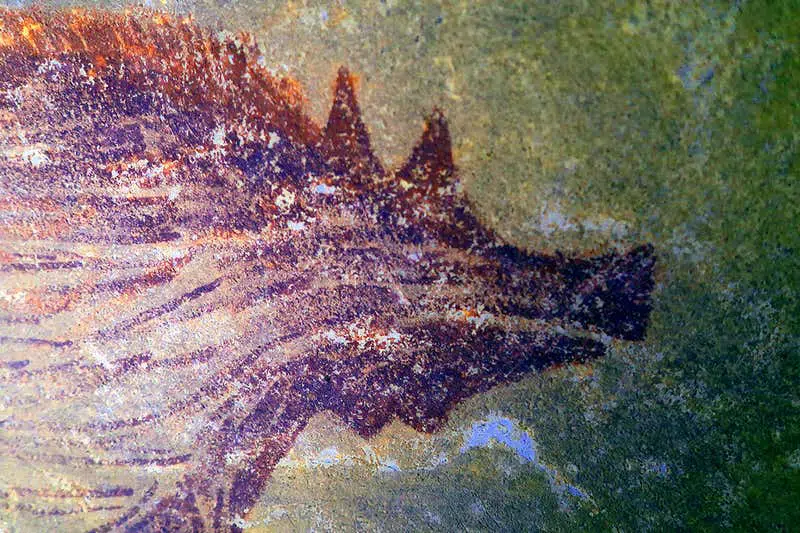

Burhan and his team began to explore the caves in the area and, a few days later, he entered one of them alone. Burhan glanced up and saw a painting of a familiar animal: a Sulawesi warty pig, a medium-sized, hairy boar with small pointy ears and short legs. Burhan had grown up with just this sort of wild pig, which is relatively common on Sulawesi, and which Burhan described to me, laughing, as a crop-destroying nuisance, akin to “a plant disease.” Gazing with recognition at this pig, Burhan also noticed the painted silhouettes of two human hands toward its rear. The over-all look of the art work suggested to Burhan that it was very old—but how old?

Thus began a long process of trying to give the cave art a proper date. Experts were brought in from Griffith. Maxime Aubert, an archeologist and geochemist, decided to use a method called uranium-series dating. He removed some of the calcite on the surface of the painting, which archeologists sometimes call “cave popcorn,” and then analyzed it. Anything under the calcite layer had to be at least as old as what was on the surface. A number of problems arose with the machine that actually did the dating—the Nu Plasma Multi Collector Inductively Coupled Plasma Mass Spectrometer. Like “a Formula One race car,” Aubert said, it requires a team of highly trained engineers just to keep it going. Still, months later, a date was handed down: the painting of the warty pig was at least 45,500 years old. This makes it the oldest known example of figurative cave art in the world.

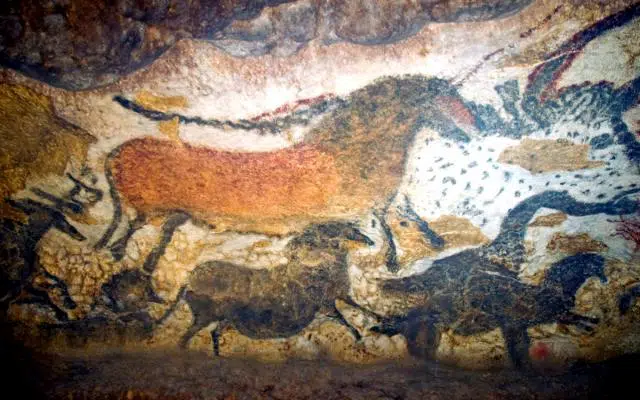

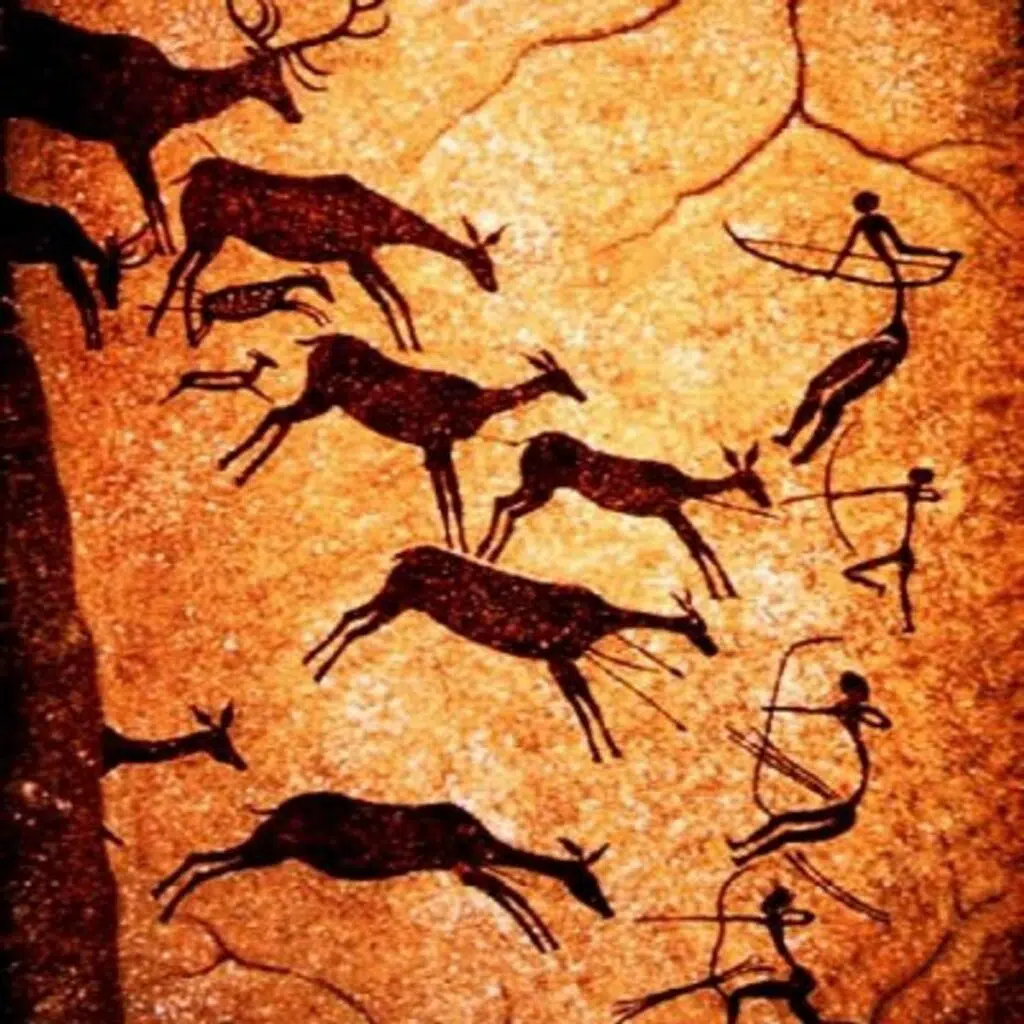

The implications of these dates are profound. The famous animal paintings in the Chauvet cave, of France, are dated at around thirty-five thousand years old; the Sulawesi warty pig outdoes them by roughly ten thousand years. Many archeologists and anthropologists talk about a “great leap forward” in human culture, suggesting that it occurred sometime between thirty thousand and sixty thousand years ago. During this “leap,” Homo sapiens are said to have initiated behaviors characteristic of modern humans. Such discoveries indicate that the leap may have occurred toward the more ancient end of that range.

Figurative cave painting, involving depictions of animals or people, isn’t the only kind of prehistoric art. The Blombos Cave, in South Africa, has yielded objects inscribed with geometric designs that are dated to be somewhere between seventy-seven thousand and a hundred thousand years old—the oldest cave art of any kind. Jean Clottes, who managed the team studying France’s Chauvet Cave from 1998 to 2002, told me that “people like us, modern humans” probably appeared in Africa around three hundred thousand years ago. Many of them would have produced images of all kinds as they spread throughout the world; finding the art they made, Clottes said, is just a “problem of discovery.” In the twentieth century, public attention was directed at European cave art, because that was where archeologists were looking for it.

Just as the discovery of the Sulawesi warty pig helps put to rest the idea that figurative cave art was unique to Europe, so, too, do the stenciled hand paintings apparently made by Neanderthals, recently uncovered in Spain, challenge our belief that art is the special provenance of Homo sapiens. The mystery that remains, of course, is why. What was the purpose of the images? “We just don’t know,” Aubert said. Clottes proposed a hypothesis: making cave paintings could have been a way to “get in touch with the supernatural spirits.” Brumm said that many more cave paintings have since been found in the area around the cave Burhan discovered; of the ones with recognisable animals, he said, “about ninety per cent are of warty pigs.” Evidently, he went on, the pre-Neolithic people who made the paintings were “obsessed” and “besotted” with the animals. There is some evidence, he told me, that the relations between humans and warty pigs on this island were more complex than previously assumed, possibly marked by a special and uniquely close association.

Chauvet Cave is designated a unesco World Heritage Site; so is the Altamira Cave, in northern Spain, which contains cave art dating to about the same time as the paintings at Chauvet. So far, the caves in Sulawesi have garnered no such protection. Burhan and Brumm describe them as being in a “secret valley”—a term they use to protect the caves, which they don’t want to be easily found. The Indonesian government is in the process of instating its own protections, but their efforts are complicated by the fact that there is mining nearby, related to the production of concrete. “Resources we currently have are still very limited to carry out conservation activities and sustainable management of the area,” Rustan Lebe, an Indonesian official who works on cultural heritage preservation issues in South Sulawesi province, wrote, in an e-mail. Petitions for help from international organizations, including unesco, are underway. In the meantime, what happens in the next few years will be crucial in determining whether the ancient art can be protected and preserved.

Burhan has since found time to polish his English; he passed the necessary exams and is now pursuing his Ph.D. in archeology at Griffith University, at the age of thirty-six. He continues to explore the caves of Sulawesi, and believes that there are many more discoveries to come. If so, it’s likely that it will be Indonesians who do the discovering. Archeology itself is of European origin, and the great finds of the past two hundred years have been credited mostly to Westerners; young archeologists such as Burhan may be harbingers of a new wave of archeology that does not assume the centrality of Europe or the West. “I felt surprise and pride,” Burhan said, of the moment when he found the cave art of the warty pig. He is glad that Sulawesi, his place of origin, is now recognized as having an especially important role in the story of human beings on Earth.