by Rory B Mackay: So, what is enlightenment?

One of the real problems is that most people can’t even agree on what enlightenment is.

Although there are many places to discuss it, it’s often a complete waste of time. An informed discussion is impossible when just about everyone has a different idea of what enlightenment actually is.

Lacking a coherent, logical definition, people are prone to erroneous notions that don’t hold up to scrutiny, not to mention magical thinking and all kinds of projections.

It’s for this reason that hardly anyone ever seems to get enlightened. This is understandable, really. You’re unlikely to reach a destination if don’t first have a clear idea of where you’re going and how to get there.

Different Ideas About Enlightenment

For some people, who probably watch too many superhero movies, enlightenment means some kind of super-human state replete with magical powers. New agers take it to mean ‘ascension’, in which the very atoms of the body are transformed into light.

Yoga sees it as the ‘merging’ of the ego with the higher Self or the attainment of higher states of consciousness.

For the Buddhists, it’s generally taken to mean nirvana, a state of no thought or desire.

Taoists talk about creating a light-body by which they can become immortal.

For some people, it means the destruction of the ego, or a state of being fully in the ‘now’.

Some teachers say that the mind can’t understand enlightenment, therefore no one can speak of it (and then charge large amounts of money for people to hear them not speak about it!). This is a cop-out of the highest order and is usually the stance of teachers who don’t have a clue themselves.

For enlightenment to mean anything, it needs a clear definition, and one that preferably makes sense.

That’s where Vedanta comes in.

Vedanta, the distilled essence of the ancient Vedas, is the granddaddy of enlightenment traditions. Assuming it’s properly taught, Vedanta provides a clear and logical definition of enlightenment and the means to attain it. Having studied just about every other teaching at some time or another, I can honestly conclude that Vedanta is the closest we have to an actual science of consciousness and enlightenment.

The proof, of course, is in the pudding.

Vedanta has been around for thousands of years now. It’s lasted all this time for a simple reason: it works. It does what it says on the label. It’s been enlightening people for millennia. With remarkable expansiveness, clarity and cohesiveness, Vedanta provides nothing less than a roadmap to freedom.

Enlightenment is Liberation From Suffering

Freedom, incidentally, is the name of the game.

The term ‘enlightenment’ isn’t all that helpful because, like the word ‘God’, it has too much baggage attached to it. It’s been misused terribly down the years.

In Vedanta, the term for enlightenment is moksha, which means liberation. And that’s what enlightenment is — liberation from suffering.

At the start of this series of articles, I explored the nature of this suffering in some depth.

The basic, existential suffering of humankind is called samsara.

Samsara is fundamentally the same in all human beings and is experienced as a deep, gnawing sense of lack, insufficiency and limitation. This sense of lack consumes us, motivating every our action and leading to a perpetual cycle of striving, seeking, frustration and pain.

This sense of being a limited, lacking self — a misapprehension caused by ignorance of our true nature — is at the very root of our suffering.

Because such a self is clearly unacceptable to us, we then spend our lives constantly chasing the objects and experiences that we vainly believe will bring us freedom — the things that will make us feel better about ourselves; that will take away our sense of lack and limitation.

The only true freedom, however, comes from challenging this misapprehension about our own basic nature.

A False Identity

As long as your mind remains fixed on the world of form, the locus of your identity remains the ahamkara, or ego.

We are all aware that we exist; that we are. The problem is where we place this ‘I-notion’. I know that I am, but what am I?

Until the mind is aware of the Self, its identification is with mithya; the world of form.

Thus, your self-identification is rooted in the body, mind, intellect, and in your memories, thoughts, desires, fears, nationality, age, gender, sexuality, level of wealth or education, and so on. These become you.

You create a narrative of who you think you are; an ad-hoc assemblage of personas; a parade of often-conflicting identities, strung together by wants, desires, fears, and goals, all competing for mental bandwidth.

When I ask who you are, you might tell me, “I’m a straight, married, middle-aged Republican doctor from Utah.”

A mind fixed on mithya is always burdened by a sense of insufficiency, lack, and limitation.

That’s because the ‘I’ has limited itself by identifying with form and thought — and a limited self is never acceptable to us.

At our core, we feel a deep, driving desire to be whole; to be complete, to be validated, to be acceptable to others and, by extension acceptable to ourselves. This is the fundamental ‘itch’ of samsara, caused by ignorance of the fact we are already whole and full, and completely acceptable as we are.

Digging around in maya, pursuing wealth, security, and pleasure can never provide a sense of wholeness, because, as we’ve seen, object-happiness is always tainted by dissatisfaction and pain.

Only knowledge of the Self, of who we truly are, can bring true wholeness and lasting happiness.

This wholeness and happiness is not a case of adding anything to ourselves. If something was added, then it could then be taken away again.

It is simply a recognition of the wholeness that was always there, as our innermost nature, previously obscured from us by maya, or avidya (ignorance). The absent-minded professor is finally ‘reunited’ with the hat that was always on top of his head the whole time.

“For the wise,” Swami Dayananda says, “there is no goal other than Brahman (the Self), which they already are.”

The jnani (liberated soul) achieves liberation from suffering, not by manipulating the maya world to his liking, but by shifting his self-identification, his I-notion, from the limited jiva to the limitless Self.

This is enlightenment.

The Self is the Knower and Not the Known

“Like two golden birds perched on the selfsame tree, intimate friends, the ego and the Self dwell in the body. The former eats the sweet and sour fruits of the tree of life, while the latter looks on in detachment.”

Mundaka Upanishad

As we saw in the last article, ‘What is the Self?’, contrary to our most fundamental assumptions about who we are, Vedanta reveals the nature of the Self to be complete fullness and limitlessness.

Unconfined by the boundaries of body and mind, the Self is pure awareness. It is eternal, deathless, ever-secure, and untouchable by any grief or suffering.

The body-mind-sense complex, or the jiva (the person we take ourselves to be) is but a superimposition that has no independent reality of its own.

Vedantic inquiry, by a process of negation, reveals that we cannot be the body or the mind.

As the Bhagavad Gita makes clear, there are only two categories in existence: the field of objects and the knower of the field. Anything known to us is an object. The knower of the object has to be other than the object.

The body is known to us as an object, as are the mind, intellect, ego, and the sense organs. The Self, therefore cannot be any of those constituent parts. It is the knower of all objects and cannot itself be objectified.

This Self is pure awareness; the changeless screen upon which the entire phenomenal world is projected like a desert mirage. This awareness is all-pervading, partless and indivisible.

In the Gita, Krishna says, “The Self is never born, thus it can never die.” While bodies die, cast aside like worn-out old clothes, the Self simply adopts new bodies. “Ever-present and changeless, it is without beginning and end.”

If the Self is limitless and untouched by anything in this world — and you ARE the Self — then your sense of lack, inadequacy and want was illegitimate to begin with.

It was based on ignorance of your nature.

Taking yourself to be a body, subject to the ravages of time, injury, sickness, and death, you are beset by limitation. But Krishna makes it clear: “You grieve over that which does not warrant grief.”

The dawning of Self-knowledge; the realization that you are, by your very nature, free, self-effulgent and the source of your own unlimited happiness, is the light that dispels the dark suffering of ignorance.

Happiness In the Self Alone

Knowing the Self to be ever-full and whole, the wise no longer seek fullness in the ever-changing world of objects. To do so would be foolish because object-happiness is always fraught with peril.

Everything in mithya is in constant motion, which means that worldly pleasures are always finite.

All such pleasures, Krishna warns, “have a beginning and end and inevitably cause pain.”

Like the rose, worldly joys may entice you with their beauty and fragrance, but they always come with thorns.

The joy of object-happiness is offset by three types of pain: the pain of acquiring it, the pain of having to preserve it, and the eventual pain of losing it.

Each pain is worse than the last, rendering all worldly joys bittersweet at best. Temporary happiness, or happiness offset by sorrow, isn’t true happiness at all.

Knowing that objects bring as much pain as they do happiness, some people attempt to withdraw from objects altogether. But this can bring its own kind of suffering. Deliberately avoiding relationships, for instance, may prevent the inherent pain of attachment and heartbreak, but this avoidance can lead to loneliness, regret, and depression.

There’s no getting around the fact that life is a zero-sum game. Seeking wholeness and happiness in the unpredictable and duality-based transactional world is clearly an unwise strategy.

The solution, then, is to find happiness and wholeness in your own Self; which is without limit, without taint, ever-free, and ever-secure.

When you know the Self to be purnah, full or whole, you no longer depend on the world of objects to make you full any more than the ocean looks to rivers for its fullness. Rivers can only supply water that belonged to the ocean in the first place. Whether the rivers flow or not, the ocean remains ever-full.

Similarly, although experiences come and go, the essential wholeness of the Self remains undiminished.

The discriminating person, understanding the limitations of object happiness, seeks the happiness that does not wane.

By mastering the mind, you come to realize the bliss that is the nature of the Self. Only in the Self do you find lasting contentment; an unchanging wholeness and satisfaction that has no beginning or end.

Thus, moving from object-happiness to Self-happiness, you attain freedom from dependence on the world of form.

The Self is Everything

The jnani (liberated soul) knows that everything in existence is the Self — is consciousness alone. They see the Self everywhere, in all things, as That which is eternally pure, ever-shining. It remains untouched by anything in this world just as the lotus is untouched by the water upon which it sits.

Such a person doesn’t lose the ability to transact with the material world. As long as the body remains, the liberated soul still has to play by the rules of transactional reality. He or she still has to eat, sleep, live, and sustain the body, and perhaps work or take care of various responsibilities.

They know, however, that action is apparent only. Though appearing as a universe of seemingly separate forms courtesy of the upadhi of maya, the Self is free from any sense of limitation. Because it’s of a different order of reality, it is unaffected by the world of matter, and by the subtle forces that drive action and experience.

The jnani, by owning this knowledge, and seeing him or herself as the Self in all beings, is thus freed from all limitation. Even amid the world of multiplicity, they see nothing but the Self. They know that karma and its results relate only to the mind and body, and never the Self.

When freed of identification with form, there is no jiva (person) at all, only the Self, and this is the highest liberation. Just as the wave is liberated by knowing that it is nothing other than the mighty ocean, the jiva is freed by the knowledge aham Brahmasmi, “I am the deathless, limitless, eternal Self”.

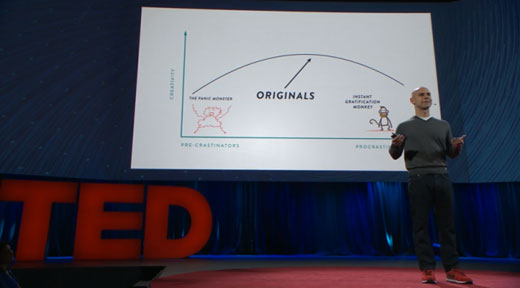

Enlightenment is Not About Chasing Experiences

It should be emphasized that moksha is not about chasing states of experience.

The human mind is experience-hungry. It’s forever seeking experiential highs. Many sincere spiritual seekers get waylaid by the mistaken belief that enlightenment is attaining certain states of consciousness or experience.

This is one of the downsides of the yoga approach. Yoga presents enlightenment as just another experience — a better experience — the experience to end all experiences!

While the materialist seeks pleasure and bliss by manipulating the objects of the external world, a yogi seeks pleasure and bliss by manipulating the inner objects of his or her mind. Both seek an experiential state of pleasure.

One must remember that all states and experiences are mithya. Like any experienceable object, such experiences are limited and time-bound. Even the greatest state of spiritual rapture is still just mithya and, no matter how wondrous it feels, it never lasts.

That’s why chasing spiritual experiences is no more the means of attaining liberation than chasing worldly objects. Becoming attached to spiritual states and ‘enlightenment experiences’ will, like any attachment, lead to raga, shoka, and moha (desire, sorrow and delusion), thus perpetuating samsaric suffering.

Another danger lies in making enlightenment an ideal. Having an ideal of what an enlightened person is like and then trying to live up to that ideal will not lead to liberation. It can, however, lead to getting lost in a more sophisticated and ‘spiritualized’ egoic self-concept.

Enlightenment is not something you have to acquire or add to yourself. You cannot do anything to ‘become’ free. Moksha is not a matter of becoming.

Vedanta reveals that you are already free. You are already the Self; deathless, eternal and all-pervading. Your problem is simply lack of knowledge about who you are.

Therefore, it is knowledge alone that liberates you by removing the obstacles that have prevented you from apprehending that freedom is your nature.

The Self-Realised Person

In the Bhagavad Gita, Krishna vividly describes a Self-realized person not so we will try to emulate or impersonate such a person, but partly to inspire us to commit to purifying the mind and attain Self-knowledge.

By knowing how the Self-realized person behaves and responds to life, we have a benchmark of sorts; a way to gauge our own progress in assimilating the knowledge of our true nature as awareness.

Krishna reveals that the enlightened soul, having mastered his or her mind, has a tranquil heart and “is free of the anxiety of always having to acquire and hoard.”

Free from binding desires, they are content in themselves alone. What greater freedom could there be than that?

Because their hearts are always full, the wise are unshaken by adversity and no longer depend on anything external for happiness.

They move about the world as freely as air, devoid of all sense of limitation, fear and craving. Such is the bliss of Self-knowledge; the liberation of knowing one’s true Self to be free of bondage and the source of all joy.

Krishna also states that the Self-realized person “renounces all desires as they appear in the mind.”

This clarifies that enlightenment is not some super-human state in which all thoughts, desires and sense of duality utterly vanish.

The jivan-muktah still has a body and mind and that body and mind continue functioning as before. Desire will arise according to past conditioning. The knower of the Self, however, is no longer dependent on external factors for his or her happiness.

Desire is no longer binding. It does not compel action. Gone is the compulsion to chase or acquire worldly objects and pleasures. The enlightened derive happiness and joy from the Self alone.

Why would you continue to seek love and happiness in the ever-changing and unpredictable mithya world, when you know there is a limitless source of love and happiness within you?

That’s why Krishna says, “Worldly craving ends when the wise come to know their own essential nature.”

Fear is also absent in the mind of the jnani. Fear is a byproduct of duality; the sense of being separate and apart from everything else. With the removal of the sense of duality, fear begins to dissolve in the light of Self-knowledge.

The jnani’s mind remains dispassionate, tranquil and stable. Such a person is, to use a Christian term, ‘in the world but not of the world.’

The jnani is naturally discriminating and unattached to outcomes. They take the good with the bad and no longer look to the external world to complete them.

A desperate entanglement with worldly objects is the hallmark of a samsari. If, owing to self-ignorance, you don’t know that wholeness is your nature, this sense of incompleteness will compel the mind to seek fulfilment through external objects.

How to Commit Spiritual Suicide

Chapter two of the Gita examines samsara from the point of view of attachment to objects.

Dwelling upon sense objects causes attachment.

Attachment inevitably leads to desire.

Advertisers know that if a child sees a toy advertised enough times they’ll begin to want that toy. The desire begins as a subtle spark, and the more the object is focused upon, the more this spark becomes a flame. When the child sees his friends playing with that same toy, his desire escalates and becomes a raging inferno.

Desire never travels alone. It comes with many problems, both when it’s fulfilled and when it’s obstructed.

When our desires are not met, we become angry.

To go back to our example, the child is likely to throw a tantrum if his parents say he can’t have the toy.

A consequence of anger is delusion and forgetfulness.

When the mind is agitated by anger and sorrow, we lose sight of our true nature, as well as our values and priorities. In the case of the spiritual seeker, the mind becomes too turbulent to contemplate on the teaching.

We begin to act on impulse, expressing our emotional disturbance in often highly dysfunctional ways.

This amounts to nothing less than spiritual suicide. We become lost in a cycle of materialistic reactivity, further reinforcing our basic sense of lack and incompleteness.

Contemplation on the Self then becomes impossible and liberation unattainable. Krishna says we become like a ship swept off-course, lost at sea and helplessly buffeted by the crashing waves of samsara.

The solution to this is reiterated throughout the Gita:

“Master your senses! Use discrimination and focus your mind on your true goal. Only knowledge, the full wisdom of the Self, will set you free.”

When your standpoint shifts from the ego to the Self, problems that previously seemed insurmountable — such as old age, sickness, family or financial problems — suddenly become insignificant in the same way that even the scariest dream loses its horror upon waking.

All of your problems are caused by ignorance of your true nature. They can be solved by shifting your identification from mithya to satya, from the jiva (ego) to the Self (awareness). That is enlightenment.

It doesn’t mean the material problems will go away, but it does mean they lose their all-consuming significance.

Moksha is the ability to weather the storms of life and to be happy regardless of whether or not external situations conform to your expectations. Your likes and dislikes become preferences only rather than binding attachments. The Self-realised naturally take an objective view of life and become emotionally independent of the world of objects.

Only by doing this, by moving from world-dependence to Self-dependence, do you find true freedom in life.

“As long as you think you are the ego, you suffer attachment and endless sorrow. But, realising you are the Self, limitless consciousness, you are freed from sorrow. When you realise you are the Self, the supreme source of love, you transcend the duality of life and enjoy the unitative state of non-duality.”

Mundaka Upanishad

The articles in this Essence of Vedanta series are excerpts from my commentary on the Bhagavad Gita, which systematically unfolds the entire teaching of Advaita Vedanta. Be sure to get your copy and enjoy the series and much more in its entirety. “Bhagavad Gita – The Divine Song” by Rory B Mackay is available on the Unbrokenself shop here.