by Chris Baraniuk: Two Native Alaskan brothers have seen climate change unfold in their lifetime. Here’s what they’ve observed…

On an isolated shoreline in northwest Alaska, a log cabin has stood watch over strengthening storms, and rising seas. The cabin was built 20 years ago by Ross Schaeffer, a member of the Iñupiat community in the town of Kotzebue, or Qikiqtaġruk as it is known in the local native Alaskan Iñupiaq language.

Kotzebue is the only town for miles around with an airstrip. It’s home to just 3,000 people but, in this part of the world, that’s considered a hive of activity. To get away from it all, Ross likes to escape to his cabin in the spring when nearby Sadie Creek swells and cuts off the rest of civilisation.

“It’s a really beautiful place to be,” says Ross. But last year, Ross was forced to raise the cabin nearly two feet (60cm) higher, to protect it from the ever-encroaching ocean. Located on a thin spit of land, largely made up of loose gravel, the retreat is vulnerable to powerful waves.

“In a few years, that ocean’s probably going to take it away,” says Ross. Other properties in the area are at risk of the same fate, he adds. The destruction is already happening. Ross has seen the wreckage of houses, once secure, lying scattered on the shore – violently dismantled by the sea.

Both Ross and his brother Bobby, who also lives in Kotzebue, can see that their world is changing. Climate change is melting the ice they rely on to travel and hunt. It is reshaping the coastline and harming the local wildlife.

For hundreds of years, Iñupiat people have adapted to live in harsh conditions. But many today are like Ross and Bobby. They worry about the startling pace of present-day climate change, and what may be at risk in their communities because of it. They worry about what else they stand to lose.

The pair were born just after World War Two – Ross in 1947, Bobby in 1949. Two children out of a total of 12, two of whom died at a young age. For the best part of a century, they’ve tracked changes in the world around them with an attention to detail that they learned, in part, from their father.

The threat of a warming, rising sea has troubled them both. “We’ve witnessed massive erosion in the last 50 years,” says Bobby. The pair contributed to scientific research published this year about how climate change is affecting hunting activities in the area.

The Arctic, Earth’s northern polar region, is warming about twice as fast as anywhere else. Indigenous groups who live there, including Iñupiat and, in Canada and Greenland, Inuit people, are experiencing profound changes in their environment, which in turn can shake their whole culture and way of life.

Each year, Ross Schaeffer has seen the ice around Kotzebue getting thinner (Credit: Sarah Betcher, Farthest North Films).

There’s plenty of scientific evidence that climate change is raising sea levels and depleting sea ice in the Arctic – but indigenous people have already seen it for themselves. Ross explains how the evidence of change at ground level is sometimes only clear to those who have watched the coast for many years. A new channel opened up across a spit near Kotzebue, for example, he says. “The ocean has taken over.” And sea ice that used to freeze solid against the shore is now much more prone to cracking and breaking away, because it is so much thinner than before.

To hunt, Iñupiat folks like Ross and Bobby often travel long distances across the ice during winter. It allows them to target species such as bearded seals, called ugruk, for example. But the sea by Ross’s cabin has stopped freezing over the way it used to. Maybe just a mile or so of ice now extends out from the shore, something he describes as “abnormal”.

“The ice should be all the way across the bay,” he says. In recent years, he’s had to more or less give up hunting on the ice either because it’s been absent, or too thin for safe travel. He has, sadly, stories to share of people from nearby villages who have died after falling through thin ice.

Although some food is available to buy in large towns in northern Alaska, most people depend on hunting and trapping to sustain themselves. Ross stores game meat in his seaside cabin. And Bobby remembers how important hunting was to their father. “Back in the 1950s, he lived almost 100% on subsistence foods,” he explains.

Koetzebue is 30 miles (48km) above the Arctic Circle (Credit: Alamy).

But in the years since, the Schaeffers have watched as climate change has put pressure on the species well-known to them, such as ringed seals. The winter of 2018 to 2019 was poor, particularly in terms of the amount of sea ice in an area the seals used for breeding, recalls Bobby. This meant the animals had less ice within which to dig their lairs.

“It affected them tremendously,” he says. “They were making lairs in thin ice and foxes and animals out there were stealing their pups for food.”

A drastic loss of sea ice could threaten ringed seal populations in various parts of the Arctic, despite the fact that these very resilient mammals can, to some extent, adapt to changing conditions.

Ross also worries about the increased run-off of freshwater into the oceans from heavier spring and summer rains.

Old Iñupiat techniques for predicting the weather are confounded by apparent changes in the way that the wind blows. “Now we have lots of south and southeast winds,” says Ross. Summer used to last four months, says Bobby. Today, he explains, it seems to go on for six.

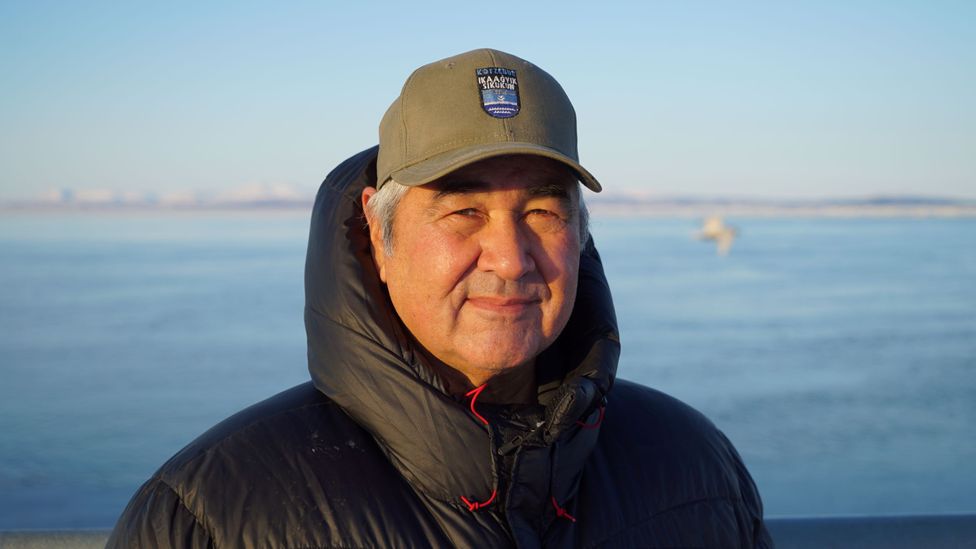

Over the last few decades, Bobby Schaeffer has watched his homeland transform (Credit: Sarah Betcher, Farthest North Films)

Then there’s the warming waters of the seas around Alaska. It can be well below zero these days in terms of air temperature, yet the sea refuses to freeze up. “It shouldn’t be open when it’s -20 to -30C (-4 to -22F) but it is,” says Ross, describing how old expectations about which parts of the sea should freeze, and when, have been turned on their head.

These changes affect the local wildlife in lots of ways. Warming waters alter the movements of fish, which in turn impacts other animals which feed on them, including kittiwakes (a kind of gull). Scientists have documented this change in Alaska but to people with a keen eye on the landscape, like Ross, it’s been obvious for some time. The birds have shifted where they tend to nest and they appear to be going to ever greater lengths to find food.

“They’re moving out from the warmer areas,” he says. “Going to the deeper water.”

Bobby remembers how his father used to notice the prevalence of certain species changing over time – such as certain insects that he’d never seen before beginning to appear around Kotzebue.

Bearded seals have been a major source of food for the Iñupiaq for thousands of years, but climate change has made life harder for them (Credit: Alamy)

This is something that many people around the world might relate to. Some animals are becoming common in places where they have not previously ventured, while others are dying out. Many butterfly species have become less common, right across the planet. The decline of a given species can often be linked directly to climate change.

The world described by Bobby and Ross is still one that is rich with resources. And their community is holding itself together tightly. But the situation they describe is a precarious one.

The rate of change witnessed by Bobby and Ross is what concerns them most. “No-one is making an effort to look at it as an emergency,” says Bobby. “When I talk to my children, I talk about these things.”

It’s hard to fathom how their community will fare in the future, he adds, though he finds the possibilities terrifying. “We’re the ones that are going to become extinct,” he says, referring to the Iñupiat.

Climate change “frightens all our people up here”, says Ross, noting that anything the world can do to slow the release of greenhouse gases and bring climate change under control is vital. “We really need to concentrate on getting that done soon,” he adds. “If we don’t focus on it, most of us ain’t gonna be here 100 years from now.”