by John Timmer: We’re on the verge of trying to fully extend the sunscreen…

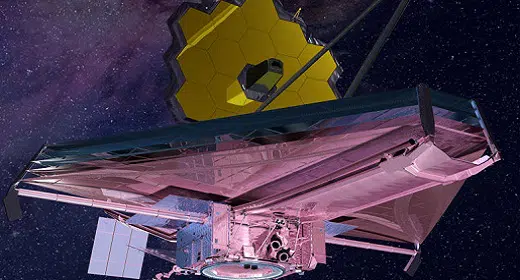

When fully operational, the James Webb Space Telescope will be enormous, with a sun shield measuring 12 x 22 meters. Obviously, however, it can’t be sent to space in that configuration. As a result, the tension of the launch will be followed by weeks of equally nerve-wracking days as different parts of the observatory are gradually unfolded.

The good news is that the process has already started, and everything has gone off without a hitch so far. Meanwhile, NASA has analyzed the results of the initial firings of the observatory’s on-board rockets, and determined that it will have enough fuel for “significantly more” than a decade of operations.

Good news on fuel

The Webb will orbit a position called the L2 Lagrange point, a site about 1.4 million kilometers from Earth. Getting into that orbit requires moving outside the plane defined by the Earth’s orbit around the Sun, and arriving at shallow angle so that the Webb doesn’t overshoot its target.

To reach the appropriate trajectory, the Webb is relying on both the initial course set by its Ariane 5 launch vehicle and a series of course adjustments powered by its onboard engines. Those onboard engines will later be responsible for making adjustments to keep the Webb in its orbit and properly oriented for observations. The more efficiently the first bits get done, the more of the latter Webb will be able to do with the remaining fuel.

The Webb has now done two course-correction firings, and its controllers have analyzed the results and the amount of fuel used. Their results? “The observatory should have enough propellant to allow support of science operations in orbit for significantly more than a 10-year science lifetime.”

The Webb team largely credit this to the Ariane 5 launcher, which greatly exceeded the minimum requirements needed to put Webb on the correct course, and a successful first course adjustment.

The launch vehicle’s performance also explains a little oddity that took place shortly after the observatory separated from the launch vehicle, when the Webb’s solar panel deployed sooner than expected. It turns out that the panels could deploy whenever the telescope had reached the right orientation relative to the Sun to produce significant power. The launch vehicle did such a good job of orienting the Webb that this happened sooner than expected, leading to the rapid extension of the panels.

Unfolding drama-free

Meanwhile the process of putting the Webb into its operational configuration has continued. The Webb’s sun shield will need to go through five distinct processes to reach its final configuration, and the first two of these are now complete. For launch, it was stowed as if it were compressed then folded in half around the telescope hardware.

In separate steps, the front and rear portions of the sun shield have now unfolded, bringing Webb to its full length for the first time since it was on Earth. The next steps there will involve extending the left and right sides, then separating out the different layers of the sun shield and adding tension that will extend them to their full size. It will be about five days before this process is complete.

Still, with the sun shield at least partially functional, NASA has now added temperature data to the “Where is Webb?” tracking website. Even without any cooling hardware operating, and without the sun shield at its full extension, the hot and cold extremes of the observatory now differ by over 160º C.

Separate from the sun shield, there’s another hardware change happening as this story’s being written. The telescope itself sits on a pedestal that raises it above the sun shield and affords it a greater field of view. As with most other hardware, that pedestal, the Deployable Tower Assembly, was in a compact position for launch; it’s now being put in its fully extended configuration. NASA says that it could take as many as six hours to complete this process.

Update: The extension of the Deployable Tower Assembly has completed successfully.