by Jon Hurdle: As wildfires worsen and sea levels rise, a small but growing number of Americans are choosing to move to places such as New England or the Appalachian Mountains that are seen as safe havens from climate change…

Researchers say this phenomenon will intensify in the coming decades.

At first, the Ashland area of southern Oregon seemed like a great place for Mich and Forest Brazil to raise their kids: It had natural beauty, plenty of open space, and a family-friendly atmosphere.

But after they moved there from the San Francisco Bay area in 2015, high summer temperatures, water shortages, and wildfire smoke became regular features of their lives, forcing them to wear face masks well before the Covid-19 pandemic, and leading them to question whether the area was the right place for them.

Then came September 8, 2020, when Forest Brazil stepped out of their rented house and had to cover his face because of smoke, dust, and debris from a fire — about three miles away — that was being water-bombed by fire-fighting planes and had provoked a panicky, high-speed evacuation on a nearby interstate.

After five years of living with fire season, it was clear to him that this was no ordinary wildfire, so he grabbed his children, gathered a few important documents from the house, and called his wife at work to say they were getting out. They picked her up and checked into a hotel, where Forest received a call from their landlord. “The house is gone,” the landlord said, and forwarded a photo taken by a neighbor showing that their home had burned to the ground.

That was the moment they knew they could no longer stay in a tinder-dry Western state, and when they became climate migrants. “I said to Mich, ‘The house is gone,’” recalled Forest, 45. “It took a couple of times saying that, and I showed her the photo, and it was just shock. Now what do we do?”

Like a growing number of Americans, the Brazil family realized they could no longer live in a place where they faced soaring temperatures and worsening wildfires driven by climate change, and so decided it was time to move to a less vulnerable part of the country. They chose New England, where Mich, a psychologist, got a transfer from her employer, the U.S. Veterans Administration, to its office in White River Junction, Vermont. After more than a year of living in a series of temporary accommodations near their former Oregon home, they moved last October to an apartment in Enfield, New Hampshire — close to the Vermont border — where they have begun to rebuild their lives.

“I can’t tell you how many times we looked at a map of the whole country and asked, ‘Where do we want to live?’” Forest said in the basement apartment where they now live with their children, ages 5, 3, and 1. “The West Coast was no longer an option. The Midwest didn’t appeal. And then looking out here, we don’t have to worry about drought and fires. We don’t have to worry about smoke and heat.”

After being forced out of their home, the Brazil family joined other Americans escaping the worsening impacts of climate change. These migrants include New Orleans residents who fled their city after Hurricane Katrina in 2005 and Houstonians who were driven out by flooding from Hurricane Harvey in 2017. Other communities have begun to disappear entirely. Residents of the coastal Louisiana community of Isle de Jean Charles, which sits just a foot or two above sea level, are being pushed out by rising seas. Inhabitants of coastal Native Alaskan villages such as Shishmaref and Newtok — where more intense storm surges caused by declining sea ice are eroding coasts weakened by melting permafrost — are being relocated.

Increasingly, worsening climate effects, including heat waves, wildfires, floods, droughts, and sea level rise, are leading a growing number of Americans to have second thoughts about where they are living and to decide to move to places that are perceived to be less exposed to these impacts, according to anecdotal reports and a growing volume of academic research. Some, like the Brazil family, are forced to move to safer areas, while others are well-to-do homeowners who are choosing to leave before fires or floods drive them out.

Flooded homes in Houston, Texas after Hurricane Harvey in August 2017. WIN MCNAMEE / GETTY IMAGES

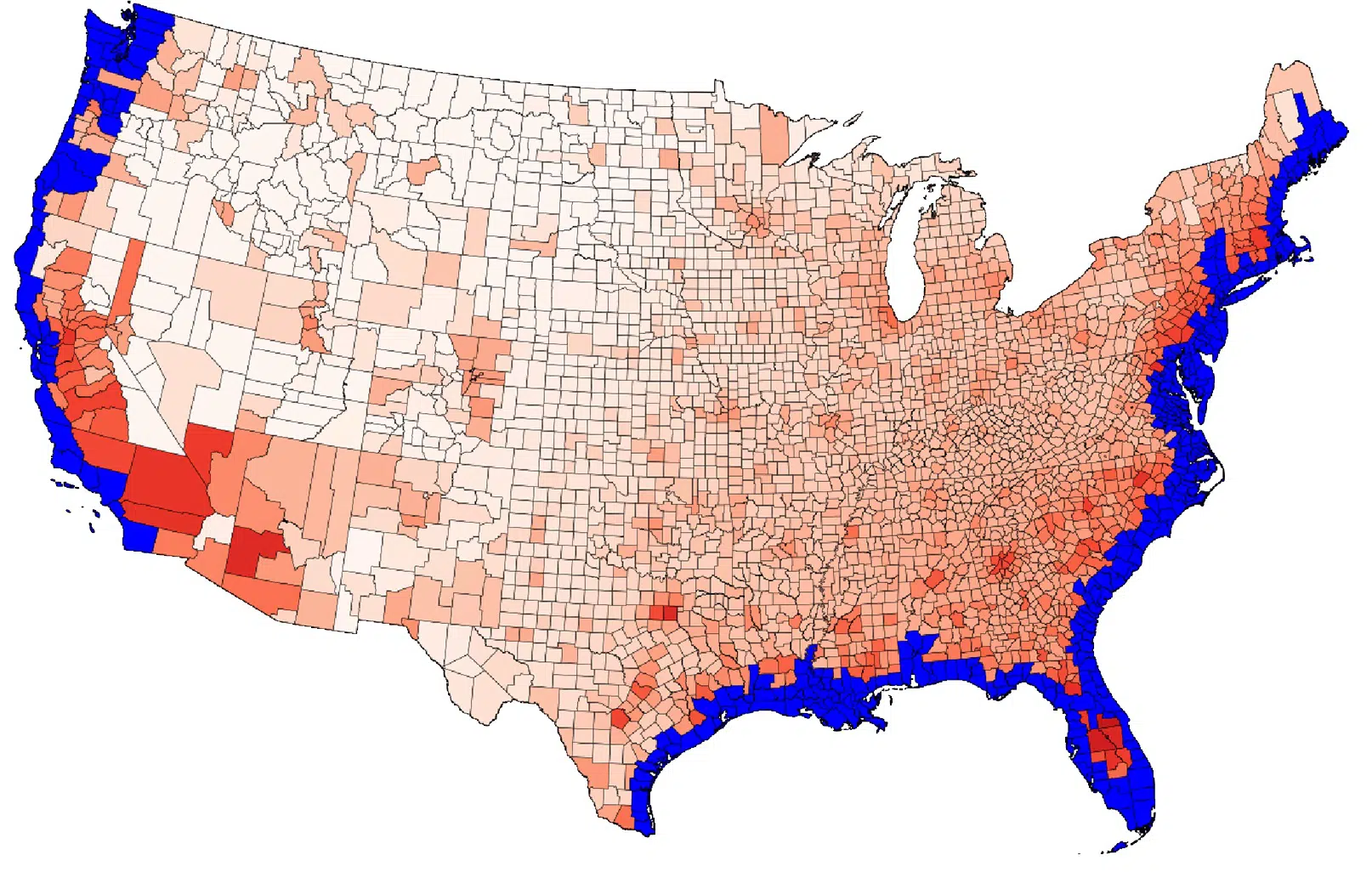

“How will people deal with extreme heat? Will they have access to potable water?” asked Jesse Keenan, an associate professor of real estate in the architecture school at Tulane University in New Orleans. “Temperate northern states will get the most inbound migration.”

Keenan, who studies the intersection of climate change adaptation and the built environment, estimated that 50 million Americans could eventually move within the country to regions such as New England or the Upper Midwest in search of a haven from severe climate impacts. He predicted that migration driven by increasingly uninhabitable coastal areas is likely to happen sooner rather than later, citing the latest federal estimate that U.S. coastal sea levels will rise by as much as a foot by 2050. Another projection, by Matthew Hauer, an assistant professor of sociology at Florida State University, is that 13.1 million Americans will relocate because of sea-level rise alone by 2100, based on projections that seas along the U.S. coast will rise by an average of 1.8 meters — nearly six feet — by then.

For Roy Parvin and his wife, Janet Vail, several years of living with wildfires around their home in northern California’s Sonoma County finally drove them some 2,600 miles to Asheville, North Carolina, where they pursue their respective careers in writing and publishing in a place where they do not have to be worried about fires, heat, or smoke.

In 2014, the couple thought they had built their dream home in the California town of Cloverdale. But three years later they experienced the first of a series of wildfires that came as close as a quarter-mile to the house. The fires finally convinced them that they could no longer live in the parched expanses of the American West.

“It just seemed like we turned down the dial on worry,” said a Californian who moved East because of wildfires.

“We left in 2020 after getting tired of being evacuated in the middle of the night by a policeman saying, ‘Pack your cars, take your dogs, don’t pick up anything, just go,’” said Parvin.

As they became convinced that they could no longer live in Sonoma, they briefly considered Bend, Oregon, but dismissed that because of its own fire problems, and Austin, Texas, but decided that would be too hot. They concluded it was time for a move out of the West altogether.

The couple decided to move to Asheville after visiting it on a book tour. They put their house up for sale 10 days before California’s Covid lockdown began in March 2020, and it quickly sold, despite the fire risk and a simultaneous exodus by some of their neighbors. Any doubt that they had made the right move was erased in 2021 when another fire destroyed a mountain cabin that they had sold when they moved to Cloverdale. “Even though we didn’t own the cabin at the time of its demise, the loss did confirm that we’d made the right decision,” he said.

Parvin, 64, said he and Vail, 63, were Cloverdale’s “first climate refugees,” all of whom were able to sell their homes for high prices, typically to wealthy San Franciscans who wanted weekend homes in the mountains despite the fire risk. “It’s part of the insanity of California — while Rome burns, they’re partying,” he said.

Proof that others aren’t as concerned about climate impacts as the Parvins can be seen in the large in-migration of people during the pandemic to places like Montana, which faces its own wildfire and water threats; Texas, where temperatures are steadily rising and are expected to soar this century; and Florida, where rising seas are projected to flood many coastal areas by 2100.

In Asheville, the Parvins are a continent away from the state where they lived for 37 years, but they enjoy living in a place where “it rains in the summer,” Roy said. “It just seemed like we turned down the dial on worry.”

No comprehensive data exists on the scale of America’s climate migration, but there is growing local evidence that it is gathering pace. In Vermont, a recent survey of about 30 people who moved to the state from many parts of the United States since the start of the pandemic found that at least a third included climate in their decisions to relocate.

“In some cases, it was people saying, ‘The wildfire smoke is too much. There’s a scarcity of water. It’s only getting worse. The heat is too great,’” said Cheryl Morse, a professor of geography at the University of Vermont, who conducted the survey in mid-2021. “They were experiencing those things firsthand where they lived, and they were imagining Vermont would be cooler, and have more seasonality, and have more water available to them, and not have wildfire smoke.”

Vermont’s new arrivals are also driven by a desire to reduce exposure to Covid-19, an ability to work remotely, and often by handsome profits on the sale of houses in more pricey urban and suburban areas, said Morse, who conducted focus groups with her respondents.

Most migrants are motivated to move by a number of factors, including climate, said Peter Nelson, a professor of geography at Middlebury College in Vermont, who observed some of Morse’s focus groups. The respondents to Morse’s survey included one couple who moved from their coastal home in Cape Cod, Massachusetts to Vermont because of concerns over more powerful storms and worries that beaches were being eroded by sea level rise.

So far, Vermont has welcomed new arrivals because its population has long been stagnant and because its employers have trouble finding workers. But its housing market doesn’t have the capacity to absorb many more people, Morse said, and home prices are rising in many parts of the state.

“We have so many open jobs, and we have been trying to think of ways to entice more people and to keep the people who are already here,” she said. “But we don’t have the housing stock. So we’re not ready.”

In the Upper Valley region straddling southern Vermont and New Hampshire, the Brazil family has been working with Kasia Butterworth, a realtor with Coldwell Banker, to find a house to buy. Butterworth said climate concerns have added to a pandemic-driven surge in demand for housing over the last two years. Prices, already fueled by a local housing shortage, have soared for new arrivals, and there’s no prospect of that changing soon, she said.

“We have zero inventory here,” she said. “I wish I could find them something to live in.”

In West Windsor, in south-central Vermont, Victoria and Will Hurd live in a house on 42 wooded acres, which they bought in early 2021 after a nationwide search for a home where they wouldn’t have to worry about heat, drought, or wildfires. The couple, previously based in Denver, almost bought houses in California, Oregon, and southern Colorado, but finally rejected them all because of climate worries.

Victoria and Will Hurd moved to Vermont from Colorado to get away from worsening fires, heat, and drought. JON HURDLE

Now, they have a property that’s home to otters and beavers, where they keep rare breeds of chickens, and where they feel protected from the worst effects of climate upheaval.

Victoria, 30, said they count themselves as climate migrants because they refused to live with growing climate threats. “We would not have ended up here had the wildfires not happened,” she said, referring to a fire that had charred the forest within three miles of a house that they had planned to buy in Oregon’s Cascade Mountains. But the couple acknowledged that nowhere is immune from climate change, as shown by Hurricane Irene, which doused Vermont with at least eight inches of rain on August 28, 2011, killing three people, destroying or damaging some 3,500 homes, and causing more than $700 million in property damage.

Victoria and Will see themselves as trailblazers and hope to persuade their friends and family to join them in the New England woods. Their migrant neighbors may soon include Will’s uncle, Steve Hurd, who, with his wife, Lauri, is considering his own move away from his native Colorado, which he said is becoming unlivable because of global warming.

“I have lived here my whole life, and I have never witnessed the intensification and acceleration of the climate drying out and heating up the way it has, and these crazy temperature variations,” said Steve Hurd, 71, a retired flight attendant.

In Enfield, New Hampshire, Mich and Forest Brazil are still coming to grips with the enormity of losing their home and their possessions, living in five places in two years, and moving across the country to a new climate and a new culture. They still feel dislocated and dispossessed and so far have been unable to afford to buy a new house, postponing any sense of closure after their upheaval, said Forest, a stay-at-home dad.

“Once we get a home and our kids are upstairs in bed, and we get a moment, we are probably just going to cry,” he said.