by Michael Irving: After losing a limb, animals like axolotls have the amazing ability to regrow a fully functional replacement, while most other creatures can only look on in envy…

But in a breakthrough new study, scientists have demonstrated how a single dose of a drug cocktail can regrow a lost limb in a frog species that doesn’t normally have any regenerative abilities.

But in a breakthrough new study, scientists have demonstrated how a single dose of a drug cocktail can regrow a lost limb in a frog species that doesn’t normally have any regenerative abilities.

Most animals have a decent ability to heal after injuries, but that doesn’t extend to lost limbs, which are far too complex to regrow with their various tissues, bones, muscles, blood vessels and nerves. Instead, scar tissue forms over the end to reduce blood loss and infection. But regeneration superpowers could be lurking in our genomes. After all, we’ve already undergone the complex process of growing the limbs the first time, and it seems that the genes and the “genetic instruction manual” are still there, dormant. So why can’t we trigger the process again as adults?

The breakthrough new study shows that it might just be possible. Researchers from Tufts University and Harvard’s Wyss Institute developed a new technique to regrow the legs of African clawed frogs, a species that usually can’t regenerate lost limbs. Exposing the wound to a drug cocktail for 24 hours was enough to trigger the growth of a new, functional leg over the next 18 months.

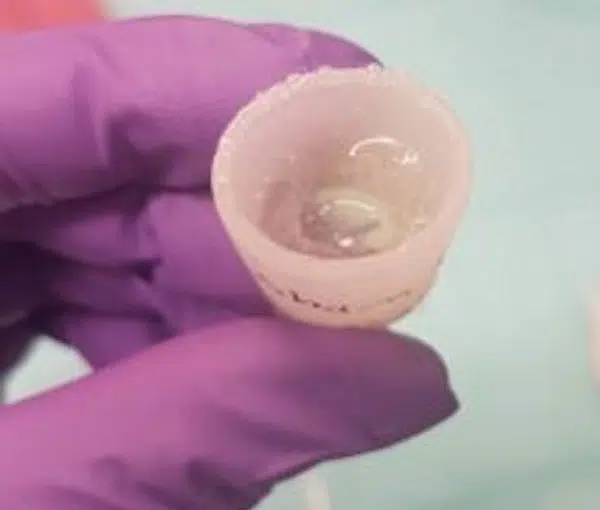

The team anesthetized the frogs and amputated one of their hind legs, then placed a silicone cap they called a BioDome over the stump. Inside this cap was a silk protein gel containing a mixture of five drugs designed to mimic the amniotic environment and encourage regeneration by reducing inflammation, inhibiting scar tissue formation, and aiding growth of new nerve fibers, blood vessels and muscles.

And sure enough, over the next 18 months the treated frogs grew new legs that were almost fully functional. They were made up of more complex combinations of tissues, including nerves and bones, although the latter didn’t have a complete structure. New, partially formed toes even grew from the ends of the limbs. The frogs could use their new legs to swim and move across land, and they responded to touch stimuli.

On closer inspection of the mechanisms behind the regeneration, the team saw that within the first few days of the treatment, molecular pathways that help embryos develop were being activated once again.

“It’s exciting to see that the drugs we selected were helping to create an almost complete limb,” said Nirosha Murugan, first author of the study. “The fact that it required only a brief exposure to the drugs to set in motion a months-long regeneration process suggests that frogs and perhaps other animals may have dormant regenerative capabilities that can be triggered into action.”

The researchers say that the next steps will involve developing the technique to grow more complete and functional limbs, and explore whether the same process could work in mammals.