by Brent Morton: In psychology, dissociation is any of a wide array of experiences from mild detachment from immediate surroundings to more severe detachment from physical and emotional experience…

The major characteristic of all dissociative phenomena involves a detachment from reality. In the era of the smartphone, Facebook, Twitter, and binge-watching Netflix, dissociation is perhaps the defining characteristic of modern American life.

As I take a look around the coffee shop I am writing this in, what strikes me is that I’m the only one looking around. Everyone else in this bustling business in the Capitol Hill neighborhood of Seattle has their nose in a laptop or a smartphone. I muse to myself that never before in history has humanity been so able to remove themselves from their immediate surroundings; that not so long ago in our history too much dissociation would be a death sentence: removal from our surroundings would mean we would not be present for the subtle snapping of a twig or movement of a shadow, and the saber-toothed tiger would get the jump on us. Now that we’ve killed all of our natural predators or put them in zoos, we can go through life in a very detached and neurotic state.

Cut Off from Ourselves

Dissociation isn’t only about being cut off from our immediate surroundings, it also includes being cut off from ourselves. A client I worked with, a very successful academic, had a history of sexual abuse and was severely somatically dissociated, meaning she had very little connection to the feeling of her body and sensuality. Another client, a manager with narcissistic tendencies, had a tyrant for a father and was dissociated from any feeling of emotional vulnerability, and thus cut off from the ability to have real meaningful human relationships. Another client was dissociated from his personal power and agency, most likely from emulating his metaphorically castrated father, and as a result experienced trauma after trauma of being bullied and humiliated by authority figures, bosses, and romantic partners.

The Freeze Response

One of the great things about modern-day neuroscience is that we now know the physiology of dissociation. Stephen Porges, Professor of Psychiatry at the University of Illinois, gifted the fields of trauma healing, contemplative practice, and psychology with Polyvagal theory. Polyvagal theory states that dissociation is actually a manifestation of the ‘freeze’ response, which is what all animals do, including the human animal, in the face of overwhelming stress. When fighting and fleeing don’t work, the dorsal part of the vagus nerve kicks in, (part of the parasympathetic nervous system), and puts the organism into the freeze/shutdown response.

This is a state characterized by shutdown, conservation, immobility, and dissociation. The gazelle running from the cheetah enters the freeze state when it has lost the race. This serves many biological survival functions, including a drastic drop in heart rate which prevents blood loss, it emulates death so the predator may lose interest if it is not a carrion feeder, and it has an anesthetic quality to it, meaning the gazelle doesn’t have to deal with the pain of being eaten alive. Dr. David Livingstone, the Scottish explorer, recorded his own experience with the freeze response triggered by his encounter with a lion on the plains of Africa:

I heard a shout. Startled, and looking half round, I saw the lion just in the act of springing upon me. I was upon a little height; he caught my shoulder as he sprang, and we both came to the ground below together. Growling horribly close to my ear, he shook me as a terrier does a rat. The shock produced a stupor similar to that which seems to be felt by a mouse after the first shake of the cat. It caused a sort of dreaminess in which there was no sense of pain nor feeling of terror, though I was quite conscious of all that was happening. It was like what patients partially under the influence of chloroform describe, who see all the operation, but feel not the knife. This singular condition was not the result of any mental process. The shake annihilated fear, and allowed no sense of horror in looking round at the beast. This peculiar state is probably produced in all animals killed by the carnivore; and if so, is a merciful provision by our benevolent Creator for lessening the pain of death.

One need not be mauled by a lion to evoke a freeze/dissociative response. The modern-day triggers of the freeze response can be as simple as emotionally mis-attuned caregivers, microaggressions in the form of systemic racism and sexism, information overload, and overwork.

A Healthy Way to Disconnect

Western psychology has traditionally pathologized all forms of dissociation, and understandably so. Disconnection from reality is a major cause of suffering personally and globally. One sees the devastating effects of dissociation in post-truth America; where scientific facts take a back seat to trauma-fueled projection. But what western psychology often misses are the potential healing and liberating qualities of the dissociation/freeze response. These healing and liberating qualities are well known, documented, and mapped in the ancient wisdom traditions of the East, including yoga, tantra, Buddhism, and Taoism, not to mention the mystical branches of Islam (Sufism), Judaism (Kabbalah) and Christianity.

Dissociative States in Indigenous Cultures

Joseph Campbell, the great professor and mythologist, found that in indigenous cultures the world over every one of them had a way of entering non-ordinary states (technically dissociative states influenced by the dorsal vagus nerve) through the sacred use of psychoactive plants, dance, drumming, ritual, or extreme exertion. In fact, one of the diagnoses for mental illness in the indigenous cultures Campbell studied was the inability to enter non-ordinary dissociative states. In other words, if you couldn’t dance yourself into an ecstatic state and talk to the gods, you were considered a psychological failure, in need of some serious help.

The major variable is how one enters the dissociative state: In the more traditional cultures, one enters with the support of the community or tribe, in a state of reverence and respect, with the wisdom of the elders guiding the experience, and a relative sense of safety. In trauma or chronic stress, one enters the dissociative states with a profound sense of fear and danger. There is a huge difference between a stressed out, overworked person puking their guts out in a cold sweat on a weekend ayahuasca ceremony and realizing the impermanence of all of existence, and someone on a month-long silent meditation retreat with good teachers and a regulated nervous system that opens up to the same truth. In the latter example, the truth is metabolized and integrated and becomes a source of well-being, ease, and freedom. In the former example, it is a traumatizing and shattering experience.

Escaping Reality

By the time I found my way to my first ten-day silent Buddhist meditation retreat in my early twenties, I was already a professional dissociator. I learned from a very early age how to dissociate, and I had a lot to dissociate from. My home environment was emotionally and physically abusive, I was raised by a single mom, and I was an emotionally sensitive child in a hyper-masculine blue-collar suburb, my public education consisting of the mind-numbing regurgitation of facts and blind submission to authority. I would lose myself in reverie, daydreams of my real parents coming to rescue me; then fantasy novels, JRR Tolkein and Isaac Asimov, comic books, television. When I reached my teens I discovered the wonders of chemically assisted dissociation in the form of marijuana, LSD, psilocybin, and MDMA. These chemicals evoked states of consciousness that I yearned for but never found in ordinary reality, states of bliss, feelings of oneness and union and connection; it felt like I was tapping into the mysteries of the cosmos. But then I’d sober up and I’d be in the suburbs again. In the words of Keith Richards, long time heavy heroin addict (heroin being perhaps the reigning champion of chemically assisted dissociation):

All the contortions we go through just not to be ourselves for a few hours.

Concentration Meditation

In the tradition of Buddhist meditation I first trained in, we started by cultivating a state of samadhi through concentration (Shamatha) practice. Samadhi practice is one of many ways one can enter into dissociative states through the Buddhist tradition, and very importantly it is seen as a preparatory phase of practice, not the end or the goal of meditation. The idea is that by the time people come to meditation practice, life has sufficiently kicked their ass to the point that their minds and nervous systems are in need of a little vacation. If one has a knack for it, one can practice concentration meditation and enter into profound states of peace, bliss, and union that rival and often surpass those offered by psychedelic substances. One learns how to dissociate in a healthy way, a way that doesn’t require the use of addictive chemicals or entertainments. This is seen as preliminary to the real work of Buddhist meditation: seeing deeply and unflinchingly into the nature of reality. In other words, a radical re-association into the beauty and horror that is human existence.

Taking a Break from Yourself

In my early/mid-twenties, however, I was not so interested in seeing deeply into the nature of reality. I was primarily interested in escaping it, which was the habit of my addicted brain. For a time I lived in a van on the streets of Seattle to save money to go on two or three-month silent meditation retreats. I was a natural at concentration meditation, and on retreat I would enter into profound states of samadhi (Jana) for weeks at a time. When samadhi is strong, the constant self-referencing thoughts that bombard us so insidiously go away. So does emotion and likes/dislikes, and even one’s personality. What is leftover are deep feelings of peace, pleasure, the feeling of floating in a benevolent sea of milk and honey. To put it another way, I got to take a long vacation from being Brent. Keith Richards would only get a few hours from his smack, I got weeks at a time from my samadhi. This was a source of great pride for me.

The bummer was coming off of retreat, and after I stopped reciting my mantra or concentrating on the breath or visualization, my personality would come back, in all its wounded and neurotic splendor. I would sober up from my samadhi fix, so to speak, and that old acronym for sober really rang true: Son Of a Bitch, Everything is Real. Samadhi practice did lots for my understanding of the nature of dissociation, how the personality constructs itself, and the peace to be found beyond the material realm. It did very little, however, in the way of improving my ability to be in the material realm, to love and work in a healthy way.

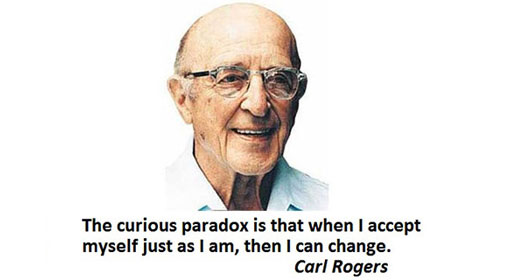

Shielding from the Truth

Mine was a classic case of the ‘spiritual bypass’. Spiritual bypassing, a term first coined by psychologist John Welwood in 1984, is the use of spiritual practices and beliefs to avoid dealing with our painful feelings, unresolved wounds, and developmental needs. Other terms for this same pattern include spiritual pride, spiritual narcissism, or spiritual materialism. Spiritual bypass shields us from the truth. While Western psychology swings too far one way pathologizing all dissociation, the spiritual bypass swings too far the other way, fetishizing dissociative states.

The spiritual bypass is especially dangerous at this time in history, not necessarily for the people engaging in it, but because this pattern often leads to negligence. Spiritual bypassing is particularly insidious and nauseating when adopted by folks of privilege. An ivory tower of spiritual pride is constructed smack dab in the middle of the fortress that is white and economic privilege, leading to a lack of empathy and action for the less fortunate.

The danger of spiritual bypassing in our time is echoed through Noam Chomsky’s critique of anti-depressants and anti-anxiety medications:

They make a situation that is unbearable bearable.

Numbing the pain through pharmaceuticals, blissing out in meditation, or soaring through the cosmos in an ayahuasca ceremony have their place; however, the danger is that the anger and anxiety evoked from injustice are bypassed rather than channeled into effective action and social change.

During my late twenties, I began to see the limitations of spiritual bypassing, primarily from a series of failed romantic relationships and work. I was also blessed with having good meditation teachers that saw what I was doing. I began to radically shift my meditation practice from concentration to open choice-less awareness, meaning rather than paying attention to one object like the breath or a mantra to the exclusion of others, I would let all of life flood in, including my neurotic thoughts, inner critic, unprocessed emotions, and whatever else. I would go on meditation retreats and rather than meditating on bliss, I would meditate on the messy phenomenon called Brent.

Standing on the Earth

I started gravitating more towards the non-dual teachings of Buddhism and away from the whole idea of the spiritual retirement home (that one day I’d magically pop into a great state of consciousness and remain there). I took inspiration from Zen Buddhist stories of the bodhisattva Monjusri, a mythological figure that would take a human form and enter the taverns and teach the drunks the dharma, then hang out with homeless people and teach them, then enter the bordellos and teach the prostitutes and johns the dharma. To me, this represented the shift of my spiritual practice from transcendence to embodiment (re-association). I began to see that my messy wounds were not obstacles to overcome, but the perfect training ground for the awakening of understanding and compassion. While spiritual bypassing is defined by trancendance, spiritual re-association is defined by the willingness to keep showing up for the messiness, vulnerability, and inevitable heartbreak of life.

Humbling is the best word I have to describe my own journey out of dissociation. Interestingly humble has the Latin root ‘humus’ meaning ‘of the earth’. Freeze and dissociation are of the sky; these days I’m much more interested in being a messy, smelly, embodied, weird human being. Re-association has the very humbling quality of making the details of one’s life much more important, because one is actually present for them. For me, this has taken the form of ending a marriage, moving out of my home, changing my career, and pretty much every other detail of my life. Similar shifts are taking place in colleagues, friends, and fellow pilgrims on this journey of embodied spirituality. This path is not for the faint of heart, but the earth desperately needs people who are actually standing on her.