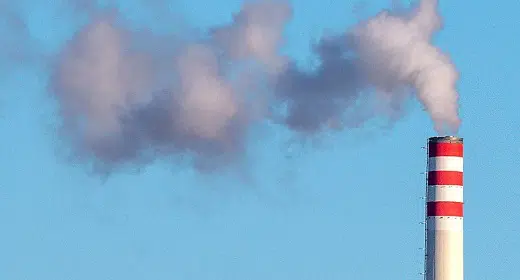

by Gail Cornwall: As one researcher put it, “Venting anger is like using gasoline to put out a fire…”

Recent headlines have shared tales of venting by everyone from Olympians to Russell Westbrook to moms meeting in a park to scream. Last year it was Ben Affleck, Meghan Markle, and parents frustrated with their school boards.

That’s unsurprising, since many of us think venting will make things feel a little better, whether it’s complaining to co-workers about a micromanaging boss or airing frustration with your partner and kids. But while blowing off steam often feels like it works to extinguish negative emotions, academic papers and clinical work with patients show it doesn’t. In fact, it often makes things worse.

The idea of venting can be traced as far back as Aristotle, but Freud is the one who really popularized the notion of catharsis. Most of what we assume about the need to “let it out” comes from his assertions about the danger of unexpressed feelings. In the “hydraulic model,” frustration and anger build up inside you and, unless periodically released in small bursts, cause a massive explosion. Starting in the 1960s, this theory was debunked by so many lab experiments that researcher Carol Tavris concluded in 1988, “It is time to put a bullet, once and for all, through the heart of the catharsis hypothesis.”

The classic setup focuses on the type of venting in which you get to express anger at someone who caused a problem. First, researchers find a way to make college students mad. Afterward, they get the opportunity to lash out, either physically or verbally. Then the researchers monitor whether venting reduces subjects’ aggression. The results consistently find that those who vent do not show lower subsequent levels of aggression; in fact, their scores for anger and aggression end up slightly higher after venting. In a 2002 study of 600 students, for example, researchers first criticized essays written by the study participants and then told some of them to hit a punching bag. Afterward, they gave them all an opportunity to blast loud noise at the person who had insulted their writing. People in the bag-hitting groups reported experiencing more anger and were more likely to blast noise than those who did nothing. The effect size was small, but still statistically significant: If the catharsis hypothesis were legit, the effect would swing in the opposite direction and be much bigger.

This same result has been replicated many times over, with opportunities to vent including everything from pounding nails with a hammer to administering real electric shocks. As one researcher put it, “Venting anger is like using gasoline to put out a fire.”

Though many studies look at anger, others extend the finding to different types of venting. In one, 178 college students completed anxiety questionnaires two and four months after the Sept. 11 attacks. Scores on anxiety questionnaires showed that those who vented their anxiety felt anxious two months after the attacks and this anxiety was around 50 percent more intense at the four-month mark. Since the students weren’t randomly assigned to either vent or not, it’s possible that the most anxious are the ones who chose to vent (so that venting was correlated with increased anxiety, not the cause of it), but another study suggests that is the less likely explanation. So does research on internet “rant-sites.” In a 2012 study, researchers found that most people who read and write rants online experience a negative shift in mood afterward.

Neuroscience—specifically, neural plasticity—explains why venting reinforces negative emotions. You can think of our brain circuitry like hiking trails. The ones that get a lot of traffic get smoother and wider, with brush stomped down and pushed back. The neural pathways that sit fallow grow over, becoming less likely to be used. Kindergarten teachers are thus spot on when they say, “The thoughts you water are the ones that grow.” This is also true for emotions, like resentment, and the ways we respond to them, like venting. The more we vent, the more likely we are to vent in the future.

Some attribute this feedback loop to self-justification. Venting our feelings at someone for, say, leaving a sink full of dirty dishes creates a need to justify having done so, and one way to do that is to rationalize that the person deserved it, which naturally gets you fired up all over again.

Why do we still do it? For starters, venting can be like scratching a mosquito bite. It feels like it works at first. Studies have shown a drop in diastolic blood pressure of 1 to 10 points after venting. But they show no attendant drop in hostility. It feels like we release anger or frustration, but we don’t. Even if we didn’t experience this temporary alleviation, there’s the fact that negative feelings naturally dissipate over time. People who do nothing assume the abatement owes to time; people who vent believe venting did the trick. And our choices can be self-reinforcing. If it seems like venting worked, we’re less likely to abide by social norms around holding back in the future.

Another culprit reinforcing the “catharsis hypothesis” is media messaging. Emotional awareness is on the rise, with more Americans understanding concepts like trauma and toxic masculinity. We’ve gotten the message that we need to acknowledge our emotions and set boundaries in our workplaces and relationships. But complaining to co-workers about your office manager switching muffin brands isn’t the same as whistleblowing, and an occasional gripe is different from constant negativity. In more general terms, embracing our feelings isn’t the same as expressing them, and not all forms of expression are created equal. Realizing “I’m angry” (always OK) is a different beast from telling someone “I’m angry” (sometimes OK), and it’s even further from berating a loved one for causing your anger (not OK). Yet pop psychology often doesn’t make these distinctions clear. TV shows and movies depict angry people displacing their aggression onto inanimate objects, throwing stuffed animals, punching pillows, and even smashing glass. We internalize the lesson and then advise one another—and our kids—to vent this way.

Recent headlines have shared tales of venting by everyone from Olympians to Russell Westbrook to moms meeting in a park to scream. Last year it was Ben Affleck, Meghan Markle, and parents frustrated with their school boards.

That’s unsurprising, since many of us think venting will make things feel a little better, whether it’s complaining to co-workers about a micromanaging boss or airing frustration with your partner and kids. But while blowing off steam often feels like it works to extinguish negative emotions, academic papers and clinical work with patients show it doesn’t. In fact, it often makes things worse.

The idea of venting can be traced as far back as Aristotle, but Freud is the one who really popularized the notion of catharsis. Most of what we assume about the need to “let it out” comes from his assertions about the danger of unexpressed feelings. In the “hydraulic model,” frustration and anger build up inside you and, unless periodically released in small bursts, cause a massive explosion. Starting in the 1960s, this theory was debunked by so many lab experiments that researcher Carol Tavris concluded in 1988, “It is time to put a bullet, once and for all, through the heart of the catharsis hypothesis.”

The classic setup focuses on the type of venting in which you get to express anger at someone who caused a problem. First, researchers find a way to make college students mad. Afterward, they get the opportunity to lash out, either physically or verbally. Then the researchers monitor whether venting reduces subjects’ aggression. The results consistently find that those who vent do not show lower subsequent levels of aggression; in fact, their scores for anger and aggression end up slightly higher after venting. In a 2002 study of 600 students, for example, researchers first criticized essays written by the study participants and then told some of them to hit a punching bag. Afterward, they gave them all an opportunity to blast loud noise at the person who had insulted their writing. People in the bag-hitting groups reported experiencing more anger and were more likely to blast noise than those who did nothing. The effect size was small, but still statistically significant: If the catharsis hypothesis were legit, the effect would swing in the opposite direction and be much bigger.

This same result has been replicated many times over, with opportunities to vent including everything from pounding nails with a hammer to administering real electric shocks. As one researcher put it, “Venting anger is like using gasoline to put out a fire.”

Though many studies look at anger, others extend the finding to different types of venting. In one, 178 college students completed anxiety questionnaires two and four months after the Sept. 11 attacks. Scores on anxiety questionnaires showed that those who vented their anxiety felt anxious two months after the attacks and this anxiety was around 50 percent more intense at the four-month mark. Since the students weren’t randomly assigned to either vent or not, it’s possible that the most anxious are the ones who chose to vent (so that venting was correlated with increased anxiety, not the cause of it), but another study suggests that is the less likely explanation. So does research on internet “rant-sites.” In a 2012 study, researchers found that most people who read and write rants online experience a negative shift in mood afterward.

Neuroscience—specifically, neural plasticity—explains why venting reinforces negative emotions. You can think of our brain circuitry like hiking trails. The ones that get a lot of traffic get smoother and wider, with brush stomped down and pushed back. The neural pathways that sit fallow grow over, becoming less likely to be used. Kindergarten teachers are thus spot on when they say, “The thoughts you water are the ones that grow.” This is also true for emotions, like resentment, and the ways we respond to them, like venting. The more we vent, the more likely we are to vent in the future.

Some attribute this feedback loop to self-justification. Venting our feelings at someone for, say, leaving a sink full of dirty dishes creates a need to justify having done so, and one way to do that is to rationalize that the person deserved it, which naturally gets you fired up all over again.

Why do we still do it? For starters, venting can be like scratching a mosquito bite. It feels like it works at first. Studies have shown a drop in diastolic blood pressure of 1 to 10 points after venting. But they show no attendant drop in hostility. It feels like we release anger or frustration, but we don’t. Even if we didn’t experience this temporary alleviation, there’s the fact that negative feelings naturally dissipate over time. People who do nothing assume the abatement owes to time; people who vent believe venting did the trick. And our choices can be self-reinforcing. If it seems like venting worked, we’re less likely to abide by social norms around holding back in the future.

Another culprit reinforcing the “catharsis hypothesis” is media messaging. Emotional awareness is on the rise, with more Americans understanding concepts like trauma and toxic masculinity. We’ve gotten the message that we need to acknowledge our emotions and set boundaries in our workplaces and relationships. But complaining to co-workers about your office manager switching muffin brands isn’t the same as whistleblowing, and an occasional gripe is different from constant negativity. In more general terms, embracing our feelings isn’t the same as expressing them, and not all forms of expression are created equal. Realizing “I’m angry” (always OK) is a different beast from telling someone “I’m angry” (sometimes OK), and it’s even further from berating a loved one for causing your anger (not OK). Yet pop psychology often doesn’t make these distinctions clear. TV shows and movies depict angry people displacing their aggression onto inanimate objects, throwing stuffed animals, punching pillows, and even smashing glass. We internalize the lesson and then advise one another—and our kids—to vent this way.

In 1999, a group of researchers investigated this media messaging theory. They had some study participants read a bogus newspaper article with pro-catharsis messaging. Sure enough, those people were later more likely to express the desire to hit a punching bag. Some were allowed to hit the bag, and others were forced to wait while researchers pretended to grapple with a computer issue. Those who hit the bag were more, not less, aggressive afterward. The researchers concluded, “It is possible that pro-catharsis media messages constitute a kind of permission that people use to justify abandoning their self-control.”

And that is likely the biggest driver of venting. Exercising restraint is hard. Protecting other people from the full brunt of our frustration—which is almost always driven by underlying fear, insecurities, and anxiety—takes work. We want to give in to the urge to wallow, to do damage, to invite company into our misery. We also can feel closer to others when we expose them to our raw emotion, and if there’s one reliable truth about human psychology, it’s that we desire connection so much that we’ll take it in negative forms when we can’t get positive ones. But venting often doesn’t work to enhance intimacy; it can even isolate us further, whether we’re talking about getting a bad rep among our colleagues for being a negative Nancy, undermining our partner’s sense of trust and safety, or having people in our social circles associate us with stress.

Venting isn’t good for us in other ways, too. When our thoughts center on how we’ve been hurt and victimized, we feel less empowered and more out of control. Fred Luskin, a forgiveness researcher at Stanford University, calls this a “grievance narrative.” In a 2006 study, Luskin and his colleagues discovered that replaying a grievance narrative both internally and externally causes our bodies to remain in a state of threat. Those who participated in a forgiveness training program felt less fired up and on edge (55th percentile for anger, compared with normal adults) than a control group (72nd percentile). Another study, which included 60 female participants, found that ruminating about ill will can significantly increase blood pressure. Scratch that bite now, and it only gets itchier later.

None of this means you should repress your emotions, never grouse to your loved ones, or otherwise lean into what Whitney Goodman writes about in the book Toxic Positivity. In fact, studies on “social sharing” show that the productiveness of this type of venting depends on how it’s done. According to a 2019 paper, “When Chatting About Negative Experiences Helps—and When It Hurts,” recounting a negative experience takes you right back there emotionally and physiologically, just like the grievance narrative research shows. That leads to an increase in negativity. Friends who respond by comforting you provide a balm in the moment, according to a 2009 paper by Bernard Rimé of the Université catholique de Louvain, but that kind of support doesn’t help process the gripe or trauma. That’s why we’ll often find ourselves hanging up with one friend and calling another. As he put it, “No consistent empirical support was found for the common view that putting an emotional experience into words can resolve it.” We “equate emotional relief with emotional recovery,” but they’re not the same, he said, making that temporary blood pressure dip make a whole lot more sense.

That said, the 2019 paper reported that chatting with friends can bring closure when they help you reconstrue an event, rather than just recount it. What does that look like? Asking why you think the other person acted that way, prodding to see whether there’s anything to be learned from it all, and just generally broadening your perspective to “the grand scheme of things.” Unfortunately, this type of meaning-making is far from common outside of therapy, according to Rimé, with social sharing conversations usually offering the discloser an increased feeling of closeness and a “sense of relief, but no effect upon their emotional recovery.”

There are lots of other things you can do when overwhelmed by negative emotion. Try “square breathing,” four breaths in and four breaths out, in order to take your body out of fight-or-flight mode. If that doesn’t work, there’s another schoolteacher trick: Cross your arms in front of you like steps five and six of the macarena; make fists, pretending one holds a bouquet and the other a candle; breathe in the roses; and blow out the flame. Psychologists call techniques like this “psychological distancing,” and studies show that they’re an effective way to defuse upsetting emotions like anger. When a modicum of calm descends, try to identify the root of your frustration by asking yourself: “Why am I so upset about this?” Ultimately, anger is like smoke. You have to get at what’s feeding the fire. After sitting with your emotions, move forward by problem-solving, scheduling a future time to discuss underlying issues, or using any number of other healthy coping mechanisms.

Just stop counting venting among them.