by Nicholas Barber: Fifty years after its premiere, Francis Ford Coppola’s classic gangster movie is still considered one of the greatest artworks made about the US, but have we overlooked a key element, asks Nicholas Barber…

Fancy watching The Godfather? It’s an offer that most of us can’t refuse. Adapted from Mario Puzo’s bestselling novel, Francis Ford Coppola’s gangster saga came second in BBC Culture’s 2015 critics poll to find the 100 greatest American films, and there aren’t many such lists that don’t have it in the top 10. Fifty years on from its release in March 1972, it stands as the defining US artwork not just on organised crime, but on immigration, capitalism and corruption. Even people who aren’t familiar with the film can recognise Marlon Brando’s weary, wheezy Mafia boss, Vito Corleone, and his favourite son Michael, played by Al Pacino. They can also quote or misquote its most memorable lines – including the one at the top of this paragraph. And its aficionados know it off by heart. In You’ve Got Mail, Tom Hanks cites it as the source of all wisdom. (“What is it about The Godfather?” sighs Meg Ryan.) The characters in The Sopranos are such enthusiasts that they name their strip club Bada Bing! after another of its lines.

Still, the fact that The Godfather should be so easily associated with a strip club raises the contentious issue of its female characters. The running time is three hours, and yet, to quote the Chicago Sun-Times’ critic, Roger Ebert: “There is little room for women in The Godfather.” Some critics have gone further. Molly Haskell wrote in the New York Times in 1997 that “Coppola’s film demeans and demotes women outrageously”. They have a point. There are no women in The Godfather as ferocious as Michelle Pfeiffer’s Elvira Hancock in Scarface (1983), or Kathleen Turner and Anjelica Huston’s characters in Prizzi’s Honor (1985).

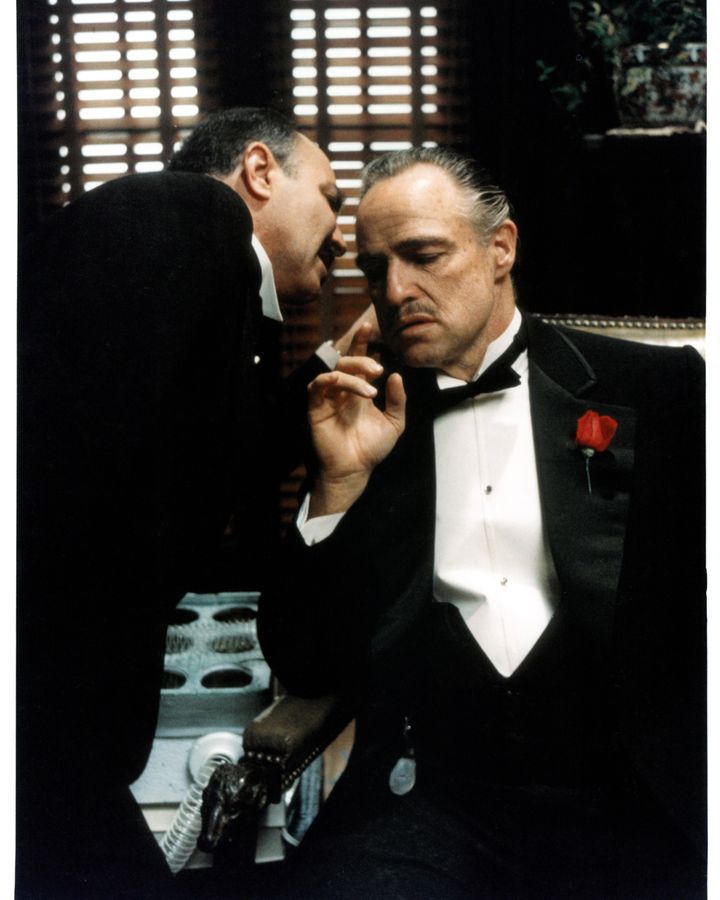

Even people who aren’t familiar with The Godfather can recognise Marlon Brando’s weary, wheezy Mafia boss, Vito Corleone (Credit: Getty Images)

While Vito, Michael and his brothers get to make deals and plan murders, pour drinks and eat Chinese takeaways, the women in their lives are left to hold the baby. The film is, among other things, a movie about hanging with your bros. Or, as David Thomson put it in Esquire magazine in 2021: “It is a movie about happiness and feeling good. And guys get it. Always have.” Providing “the most exultant glimpse of male nature in American film”, The Godfather, Thomson writes, revolves around “work, order, and the making of decisions”.

But it would be unfair to say that the film itself ignores women, even if the men in it so often do. In fact, Coppola keeps reminding us where the female characters are and how they are feeling. The opening speech is about a girl who has been abused, the closing scene has two women questioning and protesting against Michael’s methods. The most disturbingly violent sequence has Vito’s pregnant daughter Connie (Talia Shire) being whipped by her husband. And when Hollywood mogul Jack Woltz (John Marley) holds forth about a “young”, “innocent” starlet, who “was the greatest piece of ass I’ve ever had”, Coppola positions a maid in the background, forced to stand and listen to his misogynistic rant.

The Godfather isn’t a monument to male chauvinism, but a condemnation of it

As for the male Corleones’ neglect of their wives and sisters, well, let’s not forget that The Godfather is set in the 1940s and 1950s. As much as we may enjoy the performances of Shelley Winters in Roger Corman’s Bloody Mama (1970) and Madonna in Warren Beatty’s Dick Tracy (1990), Coppola rejects the idea that mid-century Mafia women were pistol-packing molls, scheming femme fatales, or matriarchs doted on by a crowd of momma’s boys. Instead, he insists, they were more likely to be pushed aside by their sexist men, who were steeped in blood and betrayal. The Godfather isn’t a monument to male chauvinism, but a condemnation of it. And it’s all too relevant, half a century after its release. When Vito attends an all-male meeting of Mafia bosses, the boardroom table is identical to those in countless photos of cabinet meetings and corporate conferences today.

Cutting off female influence

Besides, even though the men drive the plot in The Godfather, the women are vitally important to it. The bravura opening sequence is set at Connie’s wedding banquet in the Corleones’ family compound. Vito spends most of it in his shadowy study, fielding entreaties from his supplicants (an old Sicilian wedding tradition, apparently), and the dialogue keeps returning to the subject of masculinity. When Vito’s top enforcer, Luca Brasi (Lenny Montana), thanks the boss for his wedding invitation, he offers the bride and groom this faltering blessing: “And I hope that their first child be a masculine child.” Michael has a different perspective – at first, anyway. A decorated World War Two veteran, he brings his girlfriend Kay (Diane Keaton) to the wedding, shares the Corleones’ darkest secrets with her, and insists on her being included in a family photograph. But the trajectory charted by the film is his arc away from Kay and towards damnation. “[Women] will be saints in heaven while we men burn in hell,” says Vito in Puzo’s novel, and Coppola seems to agree.

The film’s bravura opening sequence is set at Connie’s wedding banquet in the Corleones’ family compound (Credit: Getty Images)

The first time we see Michael and Kay after the wedding, they are on a snowy Christmas shopping spree which could be a scene from a romantic comedy, but when Vito is wounded in a shooting, the real casualty is the couple’s closeness. Michael can no longer tell her he loves her while his associates are listening, and he leaves the hotel room where they’re having dinner to tend to his father. “I’m with you now,” he whispers in Vito’s ear.

There is a glimmering chance of redemption when Michael hides out in Sicily and falls for a peasant girl, Apollonia (Simonetta Stefanelli), who dares to challenge him. When he first lays eyes on her, she turns and strides away, and after they are married, she is confident enough to mock him and chide him. Coppola puts her behind the wheel of her husband’s car – literally in the driving seat. Could Michael settle down with a companion who is his trusted equal?

Coppola’s approach in The Godfather doesn’t ‘demean or demote’ women so much as it places them on a pedestal

Of course not. Apollonia is killed, and Michael returns to the US and the family business – no longer a smiling, tender war hero, but a reptilian tyrant who orders multiple murders, lies about them to his nearest and dearest, and professes to reject Satan at a baptism while his enemies are gunned down. By this stage, “I hope that their first child be a masculine child,” sounds more like a curse than a blessing. Michael also reunites with Kay, but his marriage proposal is no longer the stuff of romantic comedies. While Apollonia was in the driving seat, the tearful Kay is ushered into the back of a chauffeur-driven car. You could easily mistake the scene for a kidnapping.

There is a chance of redemption when Michael hides out in Sicily and falls for a peasant girl, Apollonia (Simonetta Stefanelli), who dares to challenge him (Credit: Getty Images)

In Puzo’s novel, Kay is willing to accept her place in the Corleone crime syndicate, but the film’s famous ending has Michael’s study door being closed in her distraught face so that he can strategise with his lieutenants in private. She is separated from him, just as Vito’s wife (Morgana King) was all through the film. That’s what being a Mafia boss means, it seems: being cut off from female influence.

None of this proves that the film is feminist, exactly: Coppola is too reverential towards its martyred women for that. In a Sight and Sound interview from 1972, reprinted in the current issue, he waxes lyrical about “a kind of feminine, magical quality, dating back to the Virgin Mary or something I picked up in catechism classes, that fascinates me”. And it’s true that he never paints the female Corleones in shades of grey. Kay, Apollonia and Vito’s wife never condone their husbands’ crimes, and Connie is banished to an apartment in New York after her wedding. It’s as if Coppola can’t bear the thought that they might be complicit in the men’s nefarious deeds. But his approach in The Godfather doesn’t “demean or demote” women so much as it places them on a pedestal.

The trajectory charted by the film is Michael’s arc away from Kay (Diane Keaton) and towards damnation (Credit: Getty Images)

You wouldn’t want many gangster films to have such angelic female characters. We are lucky to have had Lorraine Bracco as Karen Hill in Goodfellas (1990) and Sharon Stone as Ginger McKenna in Casino (1995), for example, as well as a new wave of female-led mob movies. In 2019’s The Kitchen, Melissa McCarthy, Tiffany Haddish and Elisabeth Moss took over their husbands’ rackets in late-1970s New York. Jennifer Lopez is due to play Griselda Blanco, a Colombian drug dealer, in The Godmother. And Jennifer Lawrence has signed on to star in Mob Girl as Arlyne Brickman, a gangster turned government witness.

These films may be a necessary corrective to The Godfather, but Coppola put more thought than most male writer-directors into what happens when women are excluded from men’s lives. After The Godfather Part II – in which Kay abandons Michael – his next film was his 1979 Vietnam War masterpiece, Apocalypse Now (also featuring Marlon Brando). Again, there are almost no women in it, and, again, the women who are in it are archetypes rather than nuanced characters. But, again, they are clearly on Coppola’s mind, in scenes ranging from the Playboy bunnies’ calamitous show for the troops, to the killing of “Mr Clean” (Laurence Fishburne) while he is listening to a recording of his mother’s voice.

As in The Godfather, the hollow left by absent women has been filled with blood. In the extended “Redux” edit of Apocalypse Now, which Coppola completed in 2001, Martin Sheen’s Willard spends a night with a widow (Aurore Clémont) on a French plantation, who tells him: “There are two of you, don’t you see? One that kills and one that loves.” Just like Michael Corleone in Sicily, he glimpses how life could be if he was one that loves rather than one that kills. But the next morning he returns to his mission on the Stygian river, on a journey away from humanity and into the heart of darkness.