by John Blake: William Peters was working as a volunteer in a hospice when he had a strange encounter with a dying man that changed his life…

The man’s name was Ron, and he was a former Merchant Marine who was afflicted with stomach cancer. Peters says he would spend up to three hours a day at Ron’s bedside, talking to and reading adventure stories to him because few family or friends visited.

When Peters plopped by Ron’s beside around lunch one day, the frail man was semi-conscious. Peters read passages from Jack London’s “Call of the Wild” as the frail man struggled to hang on. What happened next, Peters says, was inexplicable.

Peters says he felt a force jerk his spirit upward, out of his body. He floated above Ron’s bedside, looking down at the dying man. Then he glanced next to him to discover Ron floating alongside him, looking at the same scene below.

“He looked at me and he gave me this happy, contented look as if he was telling me, ‘Check this out. Here we are,’ ’’ Peters says.

Peters says he then felt his spirit drop into his body again. The experience was over in a flash. Ron died soon afterward, but Peters’ questions about that day lingered. He didn’t know what to call that moment but he eventually learned that it wasn’t unique. Peters had a “shared-death experience.”

Most of us have heard of near-death experiences. The stories of people who died and returned to life with tales of floating through a tunnel to a distant light have become a part of popular culture. Yet there is another category of near-death experiences that are, in some ways, even more puzzling.

Stories about shared-death experiences have been circulating since the late 19th century, say those who study the phenomenon. The twist in shared-death stories is that it’s not just the people at the edge of death that get a glimpse of the afterlife. Those near them, either physically or emotionally, also experience the sensations of dying.

These shared-death accounts come from assorted sources: soldiers watching comrades die on the battlefield, hospice nurses, people holding death vigils at the bedside of their loved ones. All tell similar stories with the same message: People don’t die alone. Some somehow find a way to share their passage to the other side.

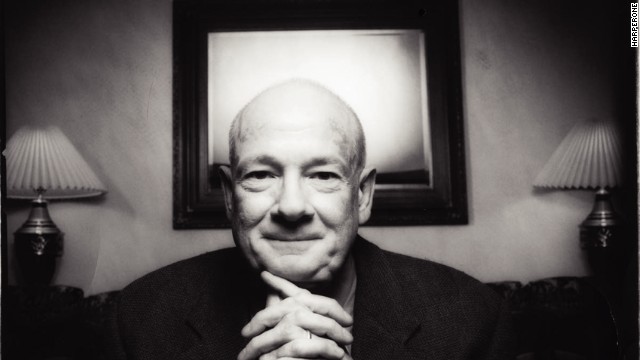

Raymond Moody coined the concept, “shared-death experiences” after spending over 20 years collecting stories about the afterlife.

HarperOne

Raymond Moody introduced the concept of the shared-death experience in his 2009 book “Glimpses of Eternity.” He first started collecting stories of people who died and returned to life while he was in medical school. Skeptics have dismissed tales of the afterlife as hallucinations triggered by anesthesia or “anoxia,” a loss of oxygen to the brain that some people experience when they’re near death.

But Moody says you can’t explain away shared-death experiences by citing anoxia or anesthesia.

“We don’t have that option in shared-death experiences because the bystanders aren’t ill or injured, and yet they experience the same kind of things,” Moody says.

Skeptics, though, say people reporting shared-death experiences are not impartial observers. Their perceptions are distorted by grief. Joe Nickell, a noted investigator into the paranormal, says people who’ve watched others die sometimes experience their own form of trauma.

They don’t intend to, but some reinvent the moment of their loss to make it more acceptable.

“If you’re having a death vigil and your loved one dies, wouldn’t it be great to have a great story to tell that would make everyone happy and tell them that ‘Uncle John’ went to heaven, and I saw his soul leave and I saw him smile,” says Nickell, who is also an investigative writer for the journal Skeptical Inquirer, which offers scientific evaluations of extraordinary claims.

Nickell says shared-death experiences are not proof of an afterlife, but of a psychological truism.

“If you’re looking for something hard enough you’ll find it,” Nickell says. “This is well known to any psychologist or psychiatrist.”

Symptoms of a near-death experience

The term shared-death experience may be new, but it went by different names centuries ago. The Society for Psychical Research in London documented shared-death experiences in the late 1800s, dubbing them “death-bed visions” or “death-bed coincidences,” researchers say.

Bidding farewell from beyond the grave?

Although “crisis apparations” — visits by the spirits of the recently departed — can be chilling, they are also comforting, say those who’ve seen them. Can bonds between loved ones defy death?

One of the first shared-death experiences to gain attention came during World War I from Karl Skala, a German poet. Skala was a soldier huddled in a foxhole with his best friend when an artillery shell exploded, killing his comrade. He felt his friend slump into his arms and die, according to one early book on shared-death experiences.

In the book, “Parting Visions,” the author Melvin Morse described what happened next to Skala, who had somehow escaped injury:

“He felt himself being drawn up with his friend, above their bodies and then above the battlefield. Skala could look down and see himself holding his friend. Then he looked up and saw a bright light and felt himself going toward it with his friend. Then he stopped and returned to his body. He was uninjured except for a hearing loss that resulted from the artillery blast.”

Moody, who coined the term shared-death experience, has arguably done more than any contemporary figure to rekindle secular interest in the afterlife. He’s been dubbed “the father of near-death experiences.“ He introduced the concept of the near-death experience in his popular 1975 book “Life after Life.”

He says he kept hearing stories about shared-death experiences during his research for “Life after Life.” A genial, chatty man, Moody says he revealed these stories in books and lectures but shared-death experiences don’t get the attention that near-death experiences get because they are more disturbing.

Few people want to think about what it’s like to die; a shared-death experience forces them to do so, he says.

“[Sigmund] Freud made the statement that we can’t imagine our own deaths,” Moody says. “In the case of a near-death experience, that happens to someone else. That is somehow more comfortable to think about.”

Proof of heaven popular, except with the church

Popular culture is filled with accounts from people who claim to have proofs of heaven. Yet the popularity of these near-death experiences raises a question: Why doesn’t the church talk about heaven anymore?

He says people who claim to have a shared-death experience tell similar stories. They recount the sensation of their consciousness being pulled upward out of their body, seeing beings of light, co-living a life review of the dying person, and seeing dead relatives of the dying person.

Some health care workers at the bedside of dying patients report seeing a light exit from the top of a person’s body at the moment of death and other surreal effects, Moody says.

“They say it’s like the room changes dimensions. It’s like a port opens up to some other framework of reality.”

Penny Sartori, who was a nurse for 21 years, says she had a deathbed vision that left her shaken. One night, she was preparing to give a bath to a dying patient who was hooked up to a ventilator and other life-prolonging equipment. She says she touched the man’s bed, and “everything around us stopped.”

She says her surroundings disappeared and “it was almost like I swapped places with him.” She says she could suddenly understand everything the man was going through, including feeling his pain. He couldn’t talk but she says she could somehow hear him convey a heart-wrenching message: “Leave me alone. Let me die in peace…just let me die.”

That shared-death experience spurred her to conduct a five-year investigation into such stories and publish them in her book “The Wisdom of Near-Death Experiences.” But even before that experience, she says she and other hospital workers had other eerie portents that a patient was about to die.

There would be a sudden drop in temperature at the bedside of a dying patient, or a light would surround the body just before death, she says.

“It’s very common for a clock to stop at the moment of death,” Sartori says. “I’ve seen light bulbs flicker or blow at the moment of death.”

A mother says goodbye?

One of the oddest shared-death experiences comes from a woman who says she felt the death throes of her mother even though she was thousands of miles away.

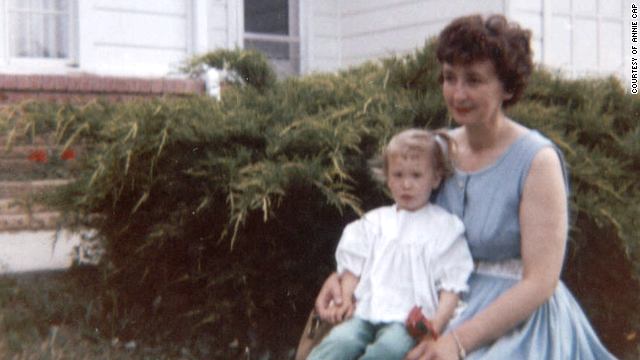

Annie Cap, as a girl, with her mother, Betty. Cap says she was close to her mom in life, and at the moment of death.

Courtesy of Annie Cap

Annie Cap was born in the United States but eventually moved to England where she worked for a telecommunications company. On the day after Christmas in 2004, she says her mother, Betty, suddenly fell ill at her home in Portland, Oregon. She was hospitalized and over the next few days all of her major organs began to shut down. Cap, however, says she didn’t know her mother was dying.

Yet in a strange way she says she did.

Cap learned that her mother was ill but says she couldn’t get a flight during the holiday season so all she could do was wait. She was in her London office with a client one day when she started to gag, struggling to breathe. She was mystified because she says she was in good health. She struggled for air for about 25 minutes, and with a growing sense of dread regarding her mother.

“I felt and heard this strange gurgling in my throat,” she says. “I started coughing and gagging. And I had this deep, growing sadness. I quickly rescheduled my client and once they had left, I ran as fast as I could to my house and called my mom’s hospital room.”

That’s when she learned that her mother was gasping for air, on the verge of death, Cap says.

While Cap was on the phone, she says, her mother died. She’s convinced that she somehow shared her mother’s death throes, but she kept denying it because she was an agnostic at the time who didn’t believe in the afterlife.

Now she says she does. Today Cap is a therapist in London, and the author of, “Beyond Goodbye: An Extraordinary True Story of a Shared Death Experience.”

“It wasn’t a blissful experience,” she says of that day after Christmas. “I was suffocating.”

The last photo taken of Annie Cap, left, and her mother, Betty.

Courtesy of Annie Cap

Skeptics question the claims

However dramatic shared-death experiences may be, they offer no more proof of an afterlife than near-death experiences, skeptics say.

Sean Carroll is a physicist who has participated in public debates about the afterlife with Moody and Eben Alexander, a neurosurgeon and author of The New York Times best-seller “Proof of Heaven.”

Life after death is dramatically incompatible with everything we know about modern science, says Carroll, author of “The Particle at the End of the Universe.” He says people who claim that a soul persists after death would have to answer other questions: What particles make up the soul, what holds them together, and how does it interact with ordinary matter?

In an essay entitled “Physics and the Immortality of the Soul,” Carroll says the only evidence of afterlife experiences is “a few legends and sketchy claims from unreliable witnesses … plus a bucket load of wishful thinking.”

“We are made of atoms,” he says. “When you die, it’s like a candle being put out or turning off a laptop. There’s no substance that leaves the body. That’s a process that stops. That’s how the laws of physics describe life.”

Nickell, the paranormal skeptic, says stories of shared-death experiences also rest on a flimsy foundation.

“That’s the problem with all of them – they’re all anecdotal evidence and science doesn’t deal with anecdotal evidence,” Nickell says.

Peters, the former hospice worker who says he had such an experience, is convinced they’re real. His encounter altered the course of his life. He eventually founded the Shared Crossing Project, a group based in Santa Barbara, California, which offers counseling, research and classes to educate people about afterlife experiences.

When asked if he could have imagined his experience with Ron, the merchant seaman, Peters says “absolutely not.”