by Lloyd Alter: A new report looks at all the impacts of meat and it’s not pretty…

Treehugger often talks about the intersection of meat consumption and sustainability. Now, these words are fittingly the title and focus of a new study, published in the journal Annual Review of Resource Economics, by Matin Qaim and Martin Parlasca of the Center for Development Research at the University of Bonn. While Treehugger focuses on the carbon footprint of meat, this study looks at the big picture, including “global meat consumption trends and the various sustainability dimensions involved, including economic, social, environmental, health, and animal welfare issues.”

Even the meat-eating treehuggers among us have always promoted the idea that vegetarian and vegan diets are the most desirable from the viewpoint of carbon and other issues. This study suggests it is more complicated than that.

Qaim writes, “At least in high-income countries, notable reductions would be desirable and important. However, nuance is required. Vegetarian lifestyles for all would not necessarily be the best option due to trade-offs in the different sustainability dimensions.”1 Nuance is not often found in discussions about food, and it is likely this study will cause some controversy.

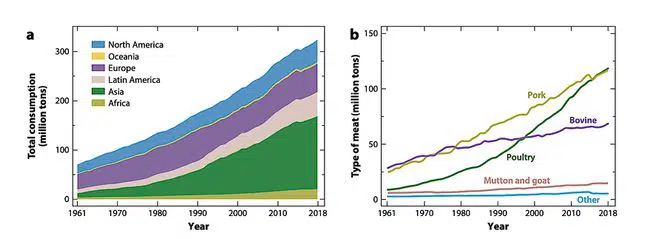

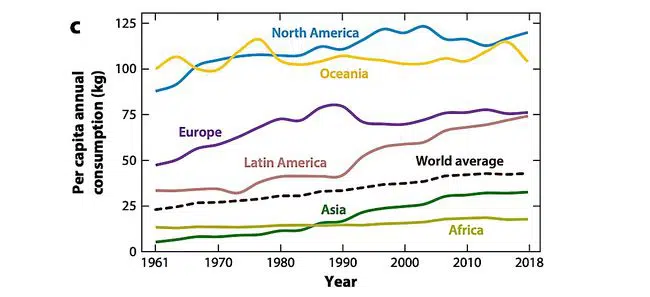

The first shocker from the study is how fast meat consumption is rising: It is growing the quickest in Asia and Latin America; this is a function of population and income growth. Pork consumption is driven by China. Chicken consumption is growing everywhere because it is cheaper and considered healthier. Meat consumption increases in parallel with income until people reach “peak meat” at an income of about $36,000 equivalents.

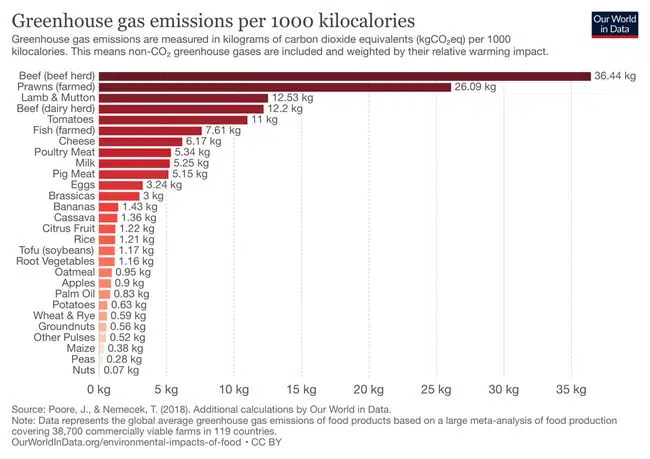

I have often made the case on Treehugger and in my book, “Living the 1.5 Degree Lifestyle,” that one has to separate beef consumption from pork and chicken, which have far lower carbon footprints. I have based this on the work of Our World in Data, showing how beef has almost seven times the emissions of chicken for the same number of calories. Qaim suggests it is not so simple.

We often discuss the question of the competition between growing food for people and food for animals, but it turns out people are competing with chickens and pigs, not cows. The study states:

“Livestock species differ considerably in terms of their feed sources and energy/protein conversion rates. Ruminants generally require more land and larger feed quantities per kilogram of meat than monogastric animals (e.g., pigs, poultry). Nonetheless, ruminants are able to digest roughage and can thus utilize low-opportunity-cost land and feed, which do not compete with human food, to produce highly nutritious protein (van Zanten et al. 2016). Monogastric animals can only digest simple carbohydrates, so their feed is more often in direct competition with human food. Hence, simple comparisons of feed or land requirements per unit of output between livestock types can be confusing.

This is confirmed by Our World in Data with its interactive chart of greenhouse gas emissions across the supply chain, where 1,000 calories of beef, pork, and chicken have an input of 1.9 kilograms, 2.9 kilograms, and 1.8 kilograms of animal feed, respectively. We have considered this issue before in the post “Are Soybeans Driving Deforestation?” suggesting then that perhaps chicken should be off the menu. As Qaim points out, it’s confusing.

The study balances the developed world’s need to reduce its consumption of meat by making the case that in many developing nations, livestock is an important source of income, employment, and female empowerment because livestock is sometimes among the few productive assets they are allowed to own. The authors write, “Some of these social functions of livestock are not always fully considered in the global sustainability discourse, even though they can be of great importance for the well-being of large population groups.”1

The study also suggests that in many countries, meat “is a rich source of essential amino acids and micronutrients, it can also help reduce nutritional deficiencies among people with limited knowledge about nutrient requirements and how to meet them through diverse plant-based diets.”1

Western-style industrial meat production is another matter, with a giant water footprint, mostly due to feed production shared equally among cows, poultry, and pigs. Greenhouse gas emissions—composed of carbon dioxide, methane, and nitrous oxides—come mostly from ruminants but also from the production of feed.

There are health problems that come from eating too much meat, notably processed meats. Again, it is complicated; low-income populations would benefit from having more meat, while “in rich countries, notable reductions in meat consumption would have positive health and environmental effects alike.”1

Finally, there are the questions of ethics and animal welfare, related to concerns about livestock nutrition, environment, health, and behavior. Yet a surprisingly small number of people are vegetarian by choice—75 million people is the number quoted—but ethical concerns are increasing.

So, we have problems of deforestation, greenhouse gas emissions, water use, health, competition for land, ethics, and animal welfare—many good reasons to give up on eating meat and go vegetarian or vegan. But Qaim and Parlasca do not come to that conclusion. Instead, they suggest we should eat less meat, particularly in richer countries.

Certainly in North America, there appear to be lots of room to do that. The authors conclude:

“Against the backdrop of planetary boundaries, high and further rising meat consumption levels are worrisome. Intensive meat production and excessive meat consumption can also be associated with negative effects on human health and animal welfare. Therefore, notable reductions in meat consumption levels would be useful and important in terms of various sustainability dimensions, at least in high-income countries.”

The report doesn’t actually say how much of a reduction is needed to reduce damage in the rich world while leaving enough for low-income countries for social and nutritional reasons. The press release from Bonn University headlines “Meat consumption must fall by at least 75%” and notes that every European Union citizen consumes 80 kilograms per year. It then quotes Qaim:

“If all humans consumed as much meat as Europeans or North Americans, we would certainly miss the international climate targets and many ecosystems would collapse. We therefore need to significantly reduce our meat consumption, ideally to 20 kilograms or less annually.”2

None of these numbers showed up in the study, but Qaim explained to Treehugger:

“The 75% number does not occur in the study. The press release is based on an interview that I had with a journalist from our University’s PR team and they were asking what all that would mean for typical consumers in Europe and other rich countries. So this is when I did some quick calculations. The number 75% is realistic, but the original paper cannot be quoted for this specific number.”

Getting down to 44 pounds or 20 kilograms of meat per year for North Americans would certainly be a challenge given that, according to Statista, the average consumption is north of 220 pounds. But it is not impossible.

In the end, the study makes a persuasive case for eating a lot less meat than we do now and also why we should be considering a lot more than just the carbon footprint, as I have tended to do. To use a word the authors of the study start and finish with, the issue of meat requires nuance.