by Jennie Tiderman-Österberg: The spellbinding refrains of the kulning call reflect a tradition that offered women freedom and independence…

These words struck me deeply. “We were born into labor and responsibility. And it has followed us our entire lives. It’s in our blood.”

It was 2017, and I was listening to recordings in the sound archive of Sweden’s Dalarnas museum. The voice belonged to Karin Saros, a Swedish woman from Mora, Dalarna, born April 20, 1887.

At the age of 13, she was sent to work for the first time on a Swedish fäbod, or summer farm, to herd the family’s cattle and make sustainable milk products for the coming winter. In this way, village women spent every summer without the company of men. Karin wrote letters to her sister describing every detail of life on the fäbod. She was 86 when she read these childhood letters for the microphone. In her voice, I hear that she speaks without most of her teeth. Her voice is low and creaky but full of melancholic remembrance and youthful longing.

She speaks not only of the labors and responsibilities but also the feelings of freedom such independent living brought to the fäbod women. The fäbod meant hard work, but Karin found comfort in leaving behind an overcrowded homelife, one deeply controlled by the patriarch of her family. On the fäbod, she herself could decide how to organize the labors of the day and as time went on, she learned how to use her voice to call on the cattle. She speaks with reverence of the often-high-pitched herding calls of the Nordic fäbod culture, known as kulning.

Sadly, I have never heard Karin Saros sing these calls. Her voice remains in the archives embedded only in a spoken story.

But the calling voice of another Karin still leaves me spellbound—Karin Edvardsson Johansson from Transtrand, Dalarna, Sweden. This Karin was born in 1909, the oldest of ten siblings. When she reached the age of five, her mother and some older women of the village taught her kulning, or kölning as it is called in Transtrand. Karin’s voice has become the soundtrack to the idea of Sweden and its fäbod culture. She received Sweden’s Zorn Badge in gold for her contributions to the kulning tradition, and she performed on radio, television and in herding music concerts. When Karin passed away in 1997, one of Sweden’s most influential newspapers published a chronicle of Karin and her deeds as a fäbod woman.

As I heard the stories and tunes from these two women, I was filled with a deep and humble respect, not only for them but for all fäbod women who carried such a heavy workload in support of their families. Their methods for refining cheese and other products from cows and goats are still used today. The knowledge they contributed makes our food craftmanship stronger and our lives better. The music they developed to keep their herds together and safe from wolves and bears was adapted by fiddlers for dancing.

Today, evidence of the labors and music of the fäbod women are found in many contemporary contexts, proof they are not just a part of our Swedish history but also the present day. This imprint on both our then and now led me to wonder about the very meaning of the word “heritage” and the impact it has upon our lives. In a globalized information society, where every cultural expression is just a click or swipe away, we often find ourselves searching, reaching for how to position ourselves. During turbulent times of pandemic, war, starvation, human trafficking, climate crisis, and other threats to community stability and safety, we reach toward a simpler foundation when the local was more present than the global, where the rural wasn’t devoured by the urban, where we formed our lives with nature instead of changing nature to suit our needs.

These things are embedded in the fäbod culture, and that is why it’s important that people in Sweden and in the Nordic countries embrace it, both as heritage and history. This is why I myself engage with it. For me, doing the work, the crafts and singing the songs of fäbod women is a way to form a physical link to Sweden’s intangible heritage. It’s the way I acknowledge and pay my respects to those women who, through the centuries, remained outside of written history. So, to reclaim this historical foundation, let’s go to the place, time and working situation where the kulning herding call was born.

Fäbod Culture in the North

The fäbod landscape comprises the wilderness belt of mountain pastures and forests that runs through the middle of Sweden, before continuing into the mountains of Norway. In the summertime, farmers moved—and still move—their herds here for grazing. A family fäbod consisted of cottages, small dairy and fire houses, and sheds for cows, goats, and sheep. When several households settled in together, this was called a fäbodvall. The women grazed their animals freely in the miles of unfenced pastures and forests surrounding these enclaves.

But why did the fäbod system exist at all? To answer this, we must examine Sweden’s human relationship with nature and its biological rhythms. In the south, the land is rich and fertile, but there is only so much of it. In the belt, the soil is glacial and very lean; the farmers needed a way to feed both humans and animals. The solution was to move the herds in the summer to where the grass matures early and is infinite.

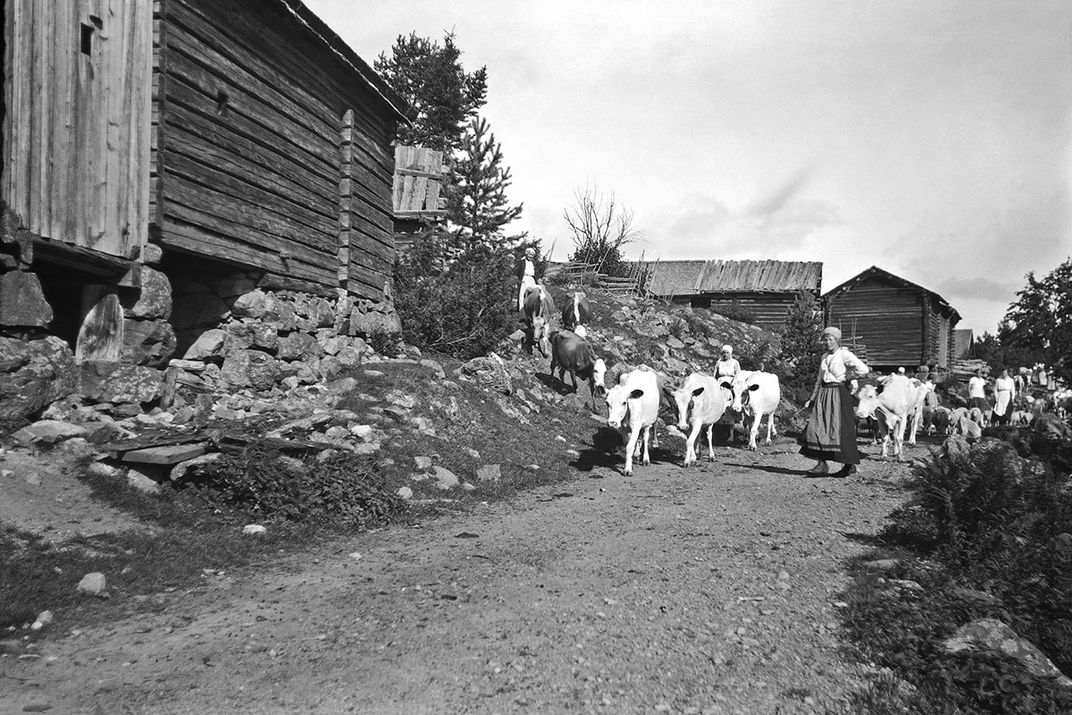

For the villages and farmers, the fäbod culture was a survival strategy. Until the early 1900s, and the birth of new land-use strategies, moving herds to the fäbod was not a choice but a rule. Each village got together and decided the date for the move to the fäbod. On that day, a torrent of hundreds of cows, goats and sheep would stream through the village and up to the mountains.

Herding cultures exist all over the world, but one thing separates the Nordic fäbod culture. Here, the shepherd was a woman, keeping her herd safe from predators, milking the cows and goats, keeping up the household and buildings, making cheese and other milk products. She could not make mistakes. The death of an animal would lead to drastic shortages. A simple error in the production of butter, cheese and whey products could bring her family to starve in winter.

Back in the village, human resources were slim, so she often went alone. She couldn’t take a break, sleep in or stay under cover on a rainy day. Even so, in archival recordings, most women speak of how arriving at the fäbod each year brought them immediate feelings of independence and freedom that overpowered the fright at being left alone in the dark, the bone-tiredness, or the slog through wetlands in raggedy clothes and broken leather shoes.

The Herding Calls of the North

Life for the fäbod women meant developing their own customs and traditions that were passed down from mother to daughter through the centuries. In this way, they created their own definition of womanhood. They developed their own musical language.

In its original context, kulning is a group of labor songs developed out of needs rather than musical expression. Women used these calls on their cattle—to release them into the forests, transfer them, get their attention—and with other shepherds—to send them greetings and messages, including warnings about predators, forest fires or other dangers. There are different ways to call on different animals, and, in some locations, each fäbod woman had their own signature melody so that everyone knew who was out in the forest.

Kulning is often described as very high and ornamented shouts, often produced within a minor scale. But many recordings show that lower pitches were practiced as well, revealing the complexity of the tradition. Where the women came from and who taught them determined how they sound. Kulning most often involves high-pitched shouts between 780 and 1568 Hz; for comparison, the frequency of a typical adult female’s speaking voice is between 165 and 255 Hz.

A kulning call is based on free phrases without a steady ground pulse, often on the vowels I and O with a start on consonants such as H and J, and sometimes S and T. The linear movement is mostly a falling melody with ornamented beats, but the consonant could often be placed as a fore beat on the octave below the main starting frequency.

Nordic Herding Music and Culture through History

Medieval sources from the north of the country include several accounts of shepherds who used animal horns to musically signal their livestock, as well as other shepherds. In the 16th century, the priest Olaus Magnus mentions this in his report to the church on the farmers of Sweden. But the blowing of horns rarely exists in the living expression of Nordic fäbod culture. Vocal signals are mentioned much later.

In the late 1680s, Johannes Columbus, tutor and professor at Uppsala University, writes of “the very weird calls of the female shepherds in the Swedish mountains.”

In the late 1700s, scholars began a movement to “rediscover” Europe’s rural music. This culminated 100 years later during a period of national romanticism. Kulning, for many ages, a part of a shepherd’s daily labor and something few would even call music, was elevated and assigned new cultural values. Postcards, paintings, poems and fiddler competitions became the framework for celebrations of fäbod culture and its characteristic music. Transcriptions of Swedish herding melodies poured forth.

Perhaps this also began the very real transition of kulning from herding sounds to herding music. During this era, herding music in general, and kulning in particular, began a process of cultural “refinement” that greatly affects how we experience kulning as something newly original, genuine, and typically Swedish today.

With the agricultural reforms of the early 1900s, the need to move herds to the mountain pastures decreased. Suddenly, harvest resources and village pastures fed both humans and animals adequately. The mid-1900s then brought the industrialization of milk production. Later that century, many fäbodvallar (mountain pastures) were abandoned, and the music of the female shepherds was almost silenced. But some continued the traditions of the fäbod.

It was not a rule to go there anymore—it was more trou

Now I am longing to leave the forest, to my home beyond the mountains.

It’s getting darker here in the forest, now when summer has left us.

Every bird has flown away, every flower is now dead and gone

The meadows have lost their richness and is now empty of flourishing grass

I am counting every day that passes by, each week becomes as long as a year

But soon my longing will rest when I am back in my father’s and mother’s home

Now I am longing to leave the paths of the forest where I have lost my way

I got astray in the dark woods, among moss, fir, heather and birch

Now I am longing to leave both the forest and the lake

Soon I will say farewell and I will go to my home

Where I can rest beside the warming fire

Kulning Today

Now, the herding calls of the women travel far beyond their forests and mountain pastures. Kulning has become a ceremonial practice and performance. It is exoticized, institutionalized, academicized, and culturally elevated, and is referred to as unique, difficult to learn, and difficult to master. It is taught in higher institutions, such as The Royal College of Music in Stockholm. Several carriers of the tradition offer their own courses.

During my first years studying kulning, I interviewed many women who work as professional folk singers. They’ve performed kulning in the most unbelievable places: intermissions at ice hockey games in the “The Globe” arena in Stockholm, at the royal castle before the King of Sweden and royal visitors from other countries, at grand openings of car fairs, as “winter music” in Martha Stewart’s Christmas Special broadcast on a U.S. television network, and as one of many traditional voices in Japanese composer Ryuichi Sakamoto’s opera Life as performed live in Tokyo.

Even Disney required kulning. When Elsa discovers her inner strength and the true power of her ice magic in the 2013 hit movie Frozen, that is kulning we hear.

From these examples, we can see that kulning is a vocal expression celebrated by many in our time. Today it moves in and between dichotomies; it is both urban and rural, performed by both farmers, old and young, and highly educated singers who learned in royal colleges or from their grandmother or aunt. Today, kulning is both operatic and traditional singing, both composed and improvised.

Kulning has traveled far through the centuries, but its biggest influence is still felt in communities and families. The many women who I have interviewed say that performing kulning makes them feel connected to our cultural heritage and feel empowered as women. To engage in this explicit and powerful vocal expression, their voices echoing toward the horizon, claiming space, affects them in a very profound way. In practicing kulning and in investing in the culture that surrounds it, they are not just expressing heritage but conceptualizing and negotiating it as well. Their investigations offer an inside-out knowledge of the voice practices, crafts, and labors of the fäbod women, creating a materialized link with the past and shining a light on our intangible heritage.

Heritage discourse is often criticized for being romantic, as it sometimes desires to freeze traditions as they once were and to exhibit them in terms of nostalgia. To balance the equation, we should take a second look at who leads the examination. The values and expressions of the rural farming women of the fäbod, are often distorted when viewed through an urban, national, or middle-class lens, often by urban-educated men.

Cultural heritage such as that of the fäbod offers us a foundation from which we can better see and make sense of our lived world today. It brings to many a sense of consistency and pride, and signals what is best to preserve and actualize within our culture. The process of defining heritage is, and should be, an organic flow of thoughts and activities that makes our encounters with history engaging. Participating in heritage practices evokes a curiosity to learn more. When vitalized, it brings us to understand why we live under the conditions and societal structures we do—because heritage was not then. It is now.

Jennie Tiderman-Österberg is an ethnomusicologist at Dalarnas museum in Sweden, a PhD student in musicology at Örebro University, and a singer. Together with herding music researcher Mitra Jahandideh, she has also initiated an international network for herding music scholars. To connect to the network, send an email to jennie.tiderman-osterberg@oru.se.

A version of this article originally appeared in the online magazine of the Smithsonian Center for Folklife and Cultural Heritage.