by Clint Rainey: In Midtown Manhattan, on the ground floor of an office building, there’s a coffee shop that’s easy to miss…

When you walk in, there’s no menu, just a metal riser supporting drinks waiting to be picked up, and in back, some plush banquettes and tables. Display cases are stocked with tidy packs of sushi and sandwiches, and shelves feature gas-station staples like Red Bull and Kettle chips. To access any of this, you pass through a turnstile that scans your palm and logs into your Amazon account. The coffee and food can be paid for without uttering a word to anybody. A sign by the door suggests, “Start with the apps.”

Marketed as “a completely different Starbucks built on effortless convenience” when it opened last November, this store—called Starbucks Pickup with Amazon Go—is the first of three that the coffee company plans to debut in New York. It is also a striking symbol of Starbucks’s quiet brand transformation from warm gathering spot to tech-enabled caffeine depot and of the challenges the company faces today. Starbucks clearly recognizes that it’s at an inflection point: The company announced on March 16 that its CEO of five years, Kevin Johnson, was stepping down. (Starbucks’s stock rose 7% on the news.)

In the 1990s, Starbucks began to position itself as “the third place,” a spot between home and work where customers could find comfort, community, and good coffee. The notion had been inspired by longtime CEO Howard Schultz’s visit to Milan’s convivial espresso bars in the late 1980s, and Starbucks has exported the experience widely, operating 34,000 stores in 84 markets. The company built upon this ethos to provide employees with “a welcoming and uplifting third place” as well, one that over the years has included generous policies such as healthcare benefits for part-time employees, a purposefully inclusive workplace, free college tuition, and paid parental leave.

Along the way, Starbucks has gotten gargantuan. It is now the third-largest global restaurant chain, after Subway and McDonald’s, and it’s growing faster than either. The company plans to add 2,000 stores this year, many of them in China, an explosive market—the company’s second largest—where, since 2020, it’s been opening a new store every 15 hours. (Starbucks fully owns and operates its stores in China.) If you’d invested $10,000 during Starbucks’s initial public offering in 1992, today it would be worth north of $3 million.

But even before the pandemic hit, the notion of creating a third place was slipping as a priority for the company. To-go orders represented 80% of transactions in 2019. One-fifth of orders were being placed through the mobile app. Cold beverages, inherently more portable than hot, were outselling hot drinks. The communal nature of the cafés was eroding, and with it Starbucks’s brand identity. Leading into 2020, executives at the company, which declined all interview requests for this article, were already casually hinting at plans to “reinvent” or “reimagine” the third place concept.

At the same time, Starbucks’s relationship with its employees was changing, too, brought on by forces both within and outside its control. Asserting that their wages were too low and worker safety was being neglected, baristas in Buffalo, New York, started organizing last summer. Since August, partners at more than 150 Starbucks stores in 27 states have filed petitions for union votes, mobilizing one of the fastest-moving union drives in U.S. history.

But this isn’t a coal mine in Alabama, or a Nabisco plant, or an Amazon warehouse. This is Starbucks, the longtime bastion of progressive capitalism, the progenitor of groundbreaking people-first policies, the first company to offer stock to even part-time employees. (That’s why Starbucks calls its baristas “partners.”) Employees aren’t supposed to rise up against a company like this. Then again, coffee shops aren’t supposed to ask for your biometric data. How did Starbucks get to this point, and how much further can it go while retaining any shred of its original brand DNA?

Schultz, who is returning to become interim CEO until an official successor to Johnson is announced in the fall, indicated in a statement that he’s aware of the issues: “Although I did not plan to return to Starbucks, I know the company must transform once again to meet a new and exciting future where all of our stakeholders mutually flourish.”Yet Schultz’s involvement hasn’t exactly been a boon thus far to the company’s employee relations, and the market pressures that Starbucks has to contend with will remain intense, meaning that extreme tech-driven efficiency measures are probably here to stay.

“They’ve done about all they can do,” says Stephanie Link, chief investment strategist at Hightower Advisors. “But the stock has languished [recently] because it is an expensive stock, and you’re not getting the results that we used to, given the macro” (Wall Street’s term for underlying trends such as the pandemic and inflation that, lately anyway, have roiled markets). She adds that Johnson delivered high single-digit total revenues, which “was impressive,” but it still amounted to “running on a treadmill just to stay still.”

On a Saturday afternoon in February, as I studied how to register my palm on the kiosk so that the turnstile’s biometric scanner would allow me into the Starbucks-Amazon store, a woman and man walked in behind me.

“Whoa,” said the man, the way someone does when they fear they’ve been caught trespassing. They approached the counter, but the barista explained they couldn’t order from him. They needed to open the Starbucks mobile app, find this particular store (59th Street between Park and Lexington), and complete their order there.

“Right now, the wait is probably going to be about 15 minutes,” the barista added.

The couple briefly gave this some thought, then retreated out the door.

Last year’s shareholder meeting marked Starbucks’s 50th anniversary. Due to COVID-19, it was entirely virtual. “We’ve positioned Starbucks for the inevitable Great Human Reconnection that is about to unfold,” president and CEO Kevin Johnson said to the camera, using the term he’s coined for society’s return to post-pandemic life. He was standing in Starbucks’s Tryer Center, the technology lab he built at the Seattle headquarters after replacing Schultz in 2017. It’s where Starbucks develops Deep Brew, the semi-omniscient artificial intelligence platform that became a focus of his.

Johnson, previously an IBM engineer, a Microsoft executive who oversaw Windows, the CEO of networking and security firm Juniper Networks, and son of a Los Alamos theoretical physicist, was nothing if not a numbers guy. And a good one: Under Johnson’s tenure as CEO, Starbucks’s stock rose by more than 50%. “I leverage data to help inform decisions,” he once explained when asked to contrast his style with Schultz’s. (Schultz tends to trust his gut.)

Johnson asserted during 2021’s annual meeting that Starbucks is “more resilient and stronger today than we were pre-pandemic,” success he attributed to a methodical “plan to reinvent the Starbucks experience” by reconfiguring stores, increasing efficiency, and analyzing Deep Brew’s data. Deep Brew is the brains behind the Starbucks mobile app, which is so popular that in recent years it has handled more mobile payments than Apple Pay or Google Pay.

Deep Brew logs order histories, geolocations, and birthdays. It attempts to tweak consumer behavior: If your store’s busy, Deep Brew may encourage you to prepay, or offer you a coupon for an Americano instead of your usual complicated latte. It also helps Starbucks juggle staff schedules, inventory levels, machine maintenance, even store expansion. Customers seem to like it, particularly during a pandemic; mobile ordering jumped 8% last year.

“These were strategic plans we put in place long ago, which we accelerated to meet this moment,” Johnson told investors during last March’s meeting. He explained that his approach since taking the helm of the company has been “to honor the mission, values, and attributes that create that special Starbucks experience while boldly reinventing for the future,” adding: “Hasn’t this very moment put that philosophy into practice?”

Starbucks has also brought in outside consultants, such as Aaron Allen of Aaron Allen & Associates, to help fine-tune efficiency in other areas, such as drive-through times. A bottleneck that emerged was “food offerings that were eight or nine syllables.” Allen explains: “Starbucks has taught us to rattle off drink orders like ‘Iced Venti Nonfat Latte with an extra shot.’ That made sense inside stores, where they didn’t want customers saying, ‘Give me the #1.’” But in the drive-through, Starbucks learned that extra syllables can cause delays. Menu boards now feature large, helpful visuals and paired food and beverage items to help simplify and expedite orders.

But employees I interviewed who are organizing (no pro-management employees I met were willing to speak on the record) said that Starbucks has shown less willingness to adjust processes and procedures to make their jobs easier. Staffing has been a point of tension. A long-standing policy at the company is that one barista should be able to finish 10 customer orders—take payment, prepare the drinks, cook any food, and hand everything off—in 30 minutes. Some baristas argue that the expectation is outdated. They say the push toward mobile ordering has actually made some things more difficult. Consumers no longer face the barista’s glare when ordering a 14-ingredient TikTok-famous drink; the Starbucks app judges them not. Starbucks has even fueled this behavior by unleashing increasingly elaborate seasonal drinks: Recall the deluge of color-changing Unicorn, Mermaid, Zombie, and Pegasus Frappuccinos.

During the pandemic, says Sara Mughal, a shift supervisor who is on her New Jersey store’s organizing committee, while she and her colleagues were appealing to Starbucks to provide N95 masks, reinstall plastic sneeze guards, and add more shifts, her team was also wrestling with drinks that seem to grow increasingly more convoluted. Her store asked for another partner to be put on drink-making duty. They received a large digital monitor instead, like the one that greets customers at the Starbucks Pickup with Amazon Go store. People can see their drink order’s place in the line. But it has to be manually updated, by a barista already working the backlogged bar, via an iPad on top of the espresso machine.

“We have built meaningful relationships with fellow coffee-lovers,” Mughal’s organizing committee wrote in a letter to Johnson in January. “What they’ve instead been getting with more frequency lately is a rushed order, thrown together by a team of baristas struggling to balance an unreasonable amount of tasks all at once. You’ve encouraged us to build connections in our communities but aren’t sharing with us the means to do so.”

IF THE PEOPLE WHO ARE SERVING THE CUSTOMER ARE NOT HAPPY, COMMITTED, AND PASSIONATE ABOUT WHAT THEY’RE DOING, THE WHOLE EXPERIENCE IS GOING TO SUCK.”

JEFFREY HOLLENDER, COFOUNDER OF THE AMERICAN SUSTAINABLE BUSINESS NETWORK AND FORMER CEO OF SEVENTH GENERATION

“I’m a Starbucks customer, and in my opinion the customer experience has deteriorated significantly over the last two to four years,” says Jeffrey Hollender, cofounder of the American Sustainable Business Council and former CEO of Seventh Generation. “AI is not going to change that. If the people who are serving the customer are not happy, committed, and passionate about what they’re doing, the whole experience is going to suck.”

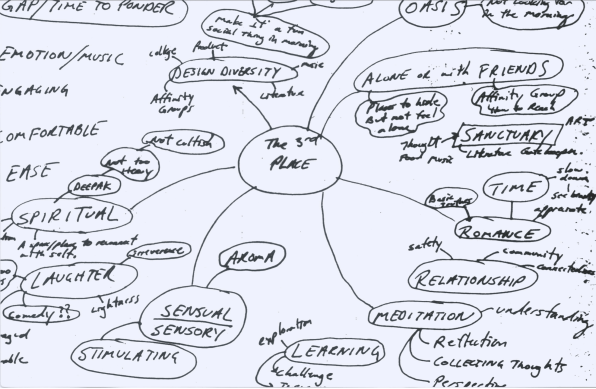

The idea of digitizing the third place is particularly jarring to Scott Bedbury, who developed the third place concept as Starbucks’s first chief marketing officer in the 1990s. (Before that, as Nike’s ad director, he created the slogan “Just Do It.”) At the time, Starbucks was on an expansion tear, gobbling up strip-mall real estate with tons of square footage that needed a unifying theme. Part of Bedbury’s job was figuring out how to define that space. In 1996, his team held a series of focus groups. Rather than being shown café mock-ups, respondents were told to close their eyes and envision the best coffee experience they could possibly fathom. “We would ask them, ‘What do you see as you step inside this place? Do you hear music? What do you taste? What do you touch?’” Bedbury recalls. “Then finally, ‘When this coffee experience is as good as it can possibly be, it can’t be any better, what do you feel?’”

He and Jerome Conlon, Starbucks’s then-branding VP, combed through these coffee shop fantasies for patterns. “The word we kept coming back to was stimulating,” he says, but not in the caffeine sense: “The feeling of being stimulated by the sounds, sights, smells, and connections of the café.” This wasn’t home, it wasn’t work; it was a moldable space in between. Bedbury shared with me a photo of the grease board where these ideas were diagrammed. In the middle, it says The 3rd place. Coming off that are words like Oasis, Sanctuary, and Meditation. Some create word chains like Laughter → comedy??, Romance → time → slow down, and Spiritual → Deepak → not too heavy → not cultish.Bedbury has since come to view the inexorable march online as a force to divide, not unite, society. “We look at what the digital world has done to this place that used to be sacred ground between places one and two, and now we find ourselves in a fourth place,” he tells me. “It’s always on, it never stops, it’s addictive, and it’s overwhelming us.”

America’s burgeoning labor movement is creating an uncomfortable situation for companies that tout a progressive ethos. REI, for example, the outdoor apparel company and customer-owned cooperative beloved by liberals, faced a union vote earlier this year: CEO Eric Artz and chief diversity officer Wilma Wallace taped a 30-minute anti-union podcast in February that began with them declaring their pronouns and apologizing for occupying Indigenous land. Employees voted to unionize anyway.

But market analysts are calling Starbucks the canary in the coal mine. Johnson said in June 2020, “We invest in people—especially our partners, so they in turn can support people in the communities we serve.” Yet the organizing workers say that Starbucks has tried to frustrate their efforts by closing stores, cutting hours, holding captive-audience meetings, and firing some of their leaders—tactics that companies like Walmart and Amazon have employed in response to union drives. This week, the National Labor Relations Board also issued its first formal complaint against Starbucks, saying it had illegally retaliated against two baristas who are organizing in Phoenix.

Even investors are calling Starbucks out: A group led by Trillium Asset Management and Parnassus Investments has written two open letters to Starbucks executives. “One reason we’ve invested in the company is they do have a very strong ESG story,” Jonas Kron, Trillium’s chief advocacy officer, tells me, referencing Starbucks’s strong environmental, social, and governance initiatives. “But we are concerned they could potentially undermine decades worth of work over the course of a few weeks” with the response to recent labor challenges. Fifty-three investors, representing $1.3 trillion in assets, signed the first letter, in December. More than 75 signed the one in March, representing $3.4 trillion.

EVERY DAY, CUSTOMERS COME IN AND WANT TO TALK ABOUT THE UNION.”

MERIDIAN STILLER, A RICHMOND, VIRGINIA-AREA STARBUCKS BARISTA

Baristas who are organizing tell me that unionization is the most frequent topic on both sides of the bar. “Every day, customers come in and want to talk about the union,” says Meridian Stiller, a Richmond, Virginia-area partner who is on their store’s organizing committee. “Writing ‘Union Yes’ on cups is like the new ‘Race Together,’” Stiller jokes, referring to the company’s well-meaning but widely mocked 2015 initiative that encouraged baristas to write those words on cups to stimulate a national conversation about race.

Rick Wartzman, director of the Drucker Institute’s KH Moon Center for a Functioning Society and author of The End of Loyalty, a book chronicling the erosion of the relationship between companies and their workers, says that “Starbucks did a great job of promoting the image that it’s better than most employers, but now that the curtain has been pulled back by their own workforce, it should serve as a cautionary tale for those of us who tend to reflexively say, ‘This company is good, and this company is bad.’” Wartzman says the lesson isn’t that Starbucks is bad, “it’s that Starbucks is now typical.”

By many measures, Starbucks is an equitable and generous employer. According to the company’s latest environmental and social impact report, 69% of its workforce is female, and 47% is minority. Executive compensation is tied to achieving diversity benchmarks, and the company pairs BIPOC managers with a corporate executive as part of a mentorship program. It boasts a 100 rating on the Human Rights Campaign’s Corporate Equality Index, and 100 on the Disability Equality Index. To date, it’s hired more than 26,000 veterans, and is more than a quarter of the way to meeting its goal of hiring 10,000 refugees by 2022 to “provid[e] a Third Place of respite for those around the world who seek it.”

But most of these initiatives are several years old. Since they launched, other companies have not just copied but advanced them. For instance, today Starbucks’s College Achievement Plan—the first of its kind back in 2014—is less comprehensive than new programs offered by Walmart, Amazon, and Target.

The company’s health plan seems less radical today as well. If an entry-level barista working 20-hour weeks chooses Starbucks’s recommended plan, 7.5% of their pay will go toward the monthly premiums, and up to another 6.8% to deductibles. The Commonwealth Fund says that a person who spends 5% of their income on the deductible alone is “underinsured,” meaning their coverage is inadequate and could cause financial hardship.

When it comes to workplace policies, the Harvard Kennedy School’s Shift Project, which does extensive tracking of service-industry work, says Starbucks is above average on some metrics (e.g., likelier than McDonald’s or Dunkin’ to give employees at least two weeks’ notice on work schedules), but well below average on others (e.g., changing schedules at the last minute). The Shift Project says Starbucks also hasn’t ended the dreaded “clopening,” a shift where a worker closes their store at night, then returns a few hours later to reopen it. The company vowed to end this practice in 2014, but Shift Project director Daniel Schneider tells me 30% of partners say they’re still doing at least one clopening per month.

Then there are wages. After organizing efforts shifted into high gear, Starbucks announced that it was making “historic investments in its partners,” including raising the wage floor to $15 an hour by this coming summer. However, $15 is what activists called a “living wage” in 2012, and it’s what Amazon started paying fulfillment-center workers back in 2018. The MIT Living Wage Calculator says that a single adult needs to earn at least $20 an hour to meet today’s minimum standard of living in New York City, $23 in the Bay Area, and $19 in Seattle. To sustain themselves in America’s most affordable county (Orangeburg, South Carolina), workers need to earn at least $14.50 an hour, according to the Economic Policy Institute’s latest Family Budget Calculator.

Meanwhile, Starbucks’s 2021 revenue was $29 billion. The company’s annual report revealed that Johnson still received a nearly 40% pay bump, even though shareholders voted against it. During the pandemic, Schultz reportedly became 50% richer; he’s now said to be worth more than $4 billion. The chain also plans to hike prices again soon, for the third time since October, and last fall pledged $20 billion in stock buybacks and dividends, money that partners like Stiller, in Virginia, note could have replenished catastrophe pay, beefed up personal protective equipment, or helped stores find creative ways to recapture their sense of a third place.

Stiller has stopped waiting for Starbucks to foster any sense of fellowship: “Partners miss that sense of community, and we feel pretty strongly that a union is a community.”

Starbucks launched an initiative in 2015 to open more cafés in underrepresented neighborhoods, to demonstrate that “it wasn’t the coffee we were selling, it was the sense of community,” as Schultz put it. The first of these Community Stores, as they were known, was located in Jamaica, Queens. It featured an on-site job-training area and partnerships with two local nonprofits.

Fourteen more Community Stores followed, and investors started to bristle. “We are asked, ‘Why is Starbucks opening stores in Bedford-Stuyvesant? We’re not in the charity business,’” Schultz said after Brooklyn’s first Community Store opened several miles from the middle class housing projects where he grew up. “There is so much of a focus on quarterly earnings, but we learned we had to make a deposit early in goodwill.”

Starbucks opened a second Community Store, in Ferguson, Missouri, less than two years after the killing of Michael Brown provoked serious unrest there.

“When I arrived in Ferguson, I immediately felt the benefit of being at a community café,” says Cordell Lewis, the store’s first manager. It partnered with the Urban League to give job training to almost 400 individuals in the community, Michael Brown’s uncle worked as a barista, and the café sought to sell products from local purveyors such as Natalie’s Cakes and More. By 2017, Starbucks was describing the Ferguson store as “a blueprint for the future.”

GOING OUT INTO THE COMMUNITY, SHOWING UP AT DIFFERENT EVENTS—STARBUCKS DID THE RIGHT THINGS TO BUILD THOSE EARLY RELATIONSHIPS.”

ELLA JONES, MAYOR OF FERGUSON, MISSOURI

“Cordell laid a great foundation,” recalls Ferguson mayor Ella Jones. “Going out into the community, showing up at different events—Starbucks did the right things to build those early relationships.”

Lewis moved up to district manager in 2019, overseeing 11 Starbucks cafés in the St. Louis area. Then the pandemic hit. He applauds Starbucks for extending catastrophe pay to sick workers. And he says that managers received thousands of dollars in quarterly bonuses even if the stores weren’t thriving. But “Starbucks really got caught with their”—he pauses, then restarts: “Hopefully they’re thinking about what their operational processes look like. I get that at the end of the day their business is to increase profits. But the whole third place concept where people come in, sit for hours, have meetings? That piece is gone.”

Lewis, who left Starbucks in January to become the general manager of a furniture store, believes the organizing effort got real in early 2021, when Seattle ended catastrophe pay and told baristas “It’s time to return to ‘business as usual.’”

Starbucks has opened eight new Community Stores since its original round of 15, and recently promised to build 1,000 by 2030. However, key executives behind the initiative have left, all while Starbucks continues to invest heavily in “new formats that reimagine the third place experience”—for instance, by opening 42 mobile-order-only Starbucks Pickup stores since 2019. Meanwhile, in Ferguson, Starbucks stopped selling Natalie’s Cakes and had retired Lewis’s Urban League job-training program before the pandemic even started.

“All the original programs, from my understanding, have kind of dwindled away,” Lewis says. “I don’t know who owns that, in Seattle or at the local level. But it wasn’t for lack of effort on the store manager’s end.” For an organization as large and smart as Starbucks, he says, “we could have shown up differently. Maybe virtual partnerships. Or at least kept the communication lines open during the pandemic by checking in. Because, hell, that’s what the rest of the world did.”

Other Community Stores have shared similar fates. Trenton, New Jersey’s store was recently moved into a different corporate district after failing to hit sales targets. Bedford-Stuyvesant’s, which occupies a space that belonged for 40 years to the discount store Fat Albert, a neighborhood institution, is now covered in graffiti. On a recent visit, I saw only two patrons inside.

On the same day, three blocks down at Bushwick Grind, a community-focused coffee shop run by a local couple, the tables were all taken and a barista explained what goes into the “sea moss smoothie.” Shelves inside stock goods from neighborhood businesses, including sea moss purveyor DrSeaMoss. Outside is a community fridge where at 4 o’clock each day workers place leftover food. The store is getting ready to open an urban garden with help from Together We Thrive, a local nonprofit that aids Black-owned businesses.

Pandemic or not, the third place exists. People will always want somewhere to gather. No one needs a green siren to call them.