by Charles Q. Choi: Next-generation towerless turbines are lightweight, more efficient, and cheaper…

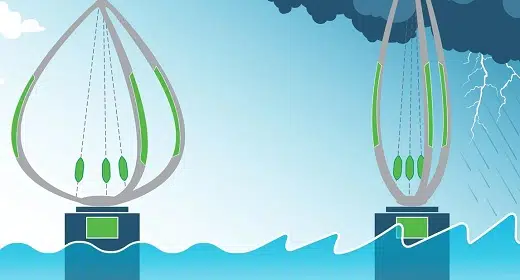

A radical new idea for offshore wind turbines would replace tall unwieldy towers that had blades on top with lightweight, towerless machines whose blades resemble the loops of a whisk. Now new software can help optimize these unusual designs to help make them a reality, researchers say.

This new work comes as the U.S. government plans to boost offshore wind energy. In March, the White House announced a national goal to deploy 30 gigawatts of new offshore wind power by 2030. The federal government suggested this initiative could help power more than 10 million homes, support roughly 77,000 jobs, cut 78 million tonnes in carbon emissions, and spur US $12 billion in private investment per year. As part of this new plan, in June, the White House and eleven governors from along the East Coast launched a Federal-State Offshore Wind Implementation Partnership to further develop the offshore wind supply chain, including manufacturing facilities and port capabilities.

One reason offshore wind is attractive is the high demand for electricity on the coasts. People often live far away from where onshore wind is the strongest, and there is not enough space in cities for enough solar panels to power them, says Ryan Coe, a mechanical engineer in Sandia National Laboratories’ water-power group in Albuquerque.

The guy wires can be shortened or lengthened to adjust the height of the blades in response to wind conditions, much as modifying the amount of tension in a bowstring can help change the curve of a bow.

However, nearly 60 percent of the accessible offshore wind in the United States blows across water more than 60 meters deep. At such depths, it would prove very expensive to build a foundation for wind turbines on the seafloor. However, this deeper offshore wind energy remains attractive, as it roughly equals the entire annual electricity consumption in the United States.

Wind turbines that can float above the seafloor could help play a key role in renewable energy. However, floating offshore wind turbines face their own challenges, such as their cost.

“Floating offshore wind is currently estimated to be three to five times more expensive than land-based wind in the United States,” says mechanical engineer Brandon Ennis, Sandia’s offshore wind technical lead in Albuquerque.

The aim of the U.S. Department of Energy’s Advanced Research Project Agency–Energy’s ATLANTIS project is to optimize the design of floating offshore wind turbines to maximize their power while minimizing their expense. The new, towerless design might help reduce both their mass and cost, Ennis says.

When it comes to land-based wind power, the turbines themselves represent about 65 percent of their levelized cost of energy—that is, their lifetime costs divided by energy production. In comparison, when it comes to floating offshore wind power, the turbines represent only about 20 percent of their levelized costs, Ennis says. Instead, their floating platforms are the biggest factors behind these costs.

“Given this difference in contribution to the levelized cost of energy of the turbine itself, it makes sense that the turbine design for floating offshore wind could be radically different than what is optimal on land,” Ennis says.

Most land-based wind turbines nowadays are horizontal-axis machines. They each possess a tower with blades that spin on a horizontal shaft, which cranks a generator behind the blades in the turbine’s nacelle, the box at the top of the turbine.

In contrast, the new design is a vertical-axis wind turbine (VAWT). These can resemble revolving doors—they each possess blades that spin on a vertical shaft, with a generator below the blades. Placing a wind turbine’s massive generator at the base of the machine instead of high up on a tower makes it much less top heavy, which reduces the size and cost of the floating platform needed to keep it afloat.

One challenge when it comes to VAWTs is protecting them from extreme winds. Traditional horizontal-axis wind turbines (HAWTs) can rotate away from intense, damaging winds, but previous VAWTs catch wind from every direction.

The new design replaces the central vertical tower often used in previous VAWTs with a set of taut wires. These wires can be shortened or lengthened to adjust the height of the blades in response to wind conditions, much as modifying the amount of tension in a bowstring can help change the curve of a bow.

his new design can help maximize each wind turbine’s energy capture while controlling strain. In addition, replacing the shaft with wires further reduces the weight of the turbine, allowing the floating platform to be significantly smaller and less expensive.

Previous VAWTs with towers often weighed more than HAWTs. In contrast, the new towerless design may weigh less than traditional HAWT designs, Ennis says.

A historical photo shows Sandia’s experimental 34-meter-diameter vertical-axis wind turbine, built in Texas in the 1980s.RANDY MONTOYA/SANDIA NATIONAL LABORATORIES

Less mass above the water level requires less mass below the water level, leading to a lighter, cheaper platform, Ennis notes. “The optimal wind energy system would remove all mass and cost that is not directly capturing energy from the wind, and the towerless VAWT design concept moves toward that goal by reducing the turbine mass and the associated platform mass,” Ennis says. Sandia filed a patent application for the new design in 2020.

However, a key challenge with all VAWTs is how they were not the focus of research as the wind industry steadily grew for the past 30 years, Ennis says. As such, where HAWTs possess software to help in their design, VAWTS did not.

Now Sandia researchers have developed a new tool to model the way in which VAWTs and their floating platforms might respond to different wind and sea conditions. This new Offshore Wind Energy Simulator (OWENS) can help optimize the design and control of these machines.

“Without a tool like ours, there cannot be a floating offshore VAWT industry, and it has been exciting to see our team advance that capability in such a short time compared to the historical development of design tools in the wind industry,” Ennis says.

The OWENS tool can also simulate land-based VAWTs. Moreover, with some modifications, it can model unconventional HAWTs, such as bi-wing blades or shrouded concepts, as well as cross-flow marine hydrokinetic turbines, which are essentially VAWTs submerged in water instead of air, Ennis says.

Popular misinformation does exist concerning VAWTs, Ennis says. “People claim that VAWTs have lower aerodynamic performance,” he says. “That’s wrong. Lift-based VAWTs are predicted to have the ability to slightly exceed the maximum efficiency of a horizontal-axis wind turbine.”

Ennis does note that “VAWTs that were commercialized in the ’90s had fatigue issues. They also used aluminum blades with bolted joints, which is almost the worst material decision you could make for fatigue, and the design standards weren’t sufficient to characterize the operational life of a wind turbine.” However, modern designs can overcome these concerns, he says.

The researchers are validating OWENS with a land-based 34-meter-diameter VAWT built at Sandia in the ’80s. This research can eventually help certify VAWT models against pertinent design standards. They plan to submit their findings to the journal Wind Energy Science.

The scientists hope to have an optimized floating VAWT design by the end of the year, Ennis says. They next aim to have a small physical demo machine to verify its performance.

“Vertical-axis wind turbines offer some meaningful advantages over traditional horizontal-axis wind turbines, particularly for floating offshore wind energy,” Ennis says. “With our new design software, we are in a good position to evaluate just how significant these advantages might be for our towerless VAWT system.”