by Brett & Kate McKay: Almost twenty million self-help books were sold last year…

But the popularity of self-help literature is hardly a modern phenomenon.

Some of the writings of ancient Greek and Roman philosophers arguably fall into the personal development category. So do pieces of literature that were written every century after their time.

In a way, this can seem like a very depressing fact. After all, if the purpose of self-improvement books is to offer advice capable of solving people’s problems, then the fact that new entries have continuously been added to the genre for millennia means that none of the tips they espouse actually work.

But that is not the real value of self-improvement literature. The problems of being human — laziness, selfishness, awkwardness, distractibility — are not fixable; they are intractable. The best that self-help books can do for us is to take the principles attendant to living the good life — which really never change — and refresh and solidify them anew. The worth of reading self-help literature is in the way it can move values and ideas that tend to drift to the back of consciousness up to the forefront. The more we can keep our ideals at the top of our minds, the more they can influence our choices and behavior, and help us prevent, mitigate, and sand off the roughest edges of our perennial problems.

Not all self-improvement books perform this function equally well, and we would argue that old self-help literature does it best.

If the value of personal improvement books lies in their ability to activate your higher, but-all-too-often latent impulses, the more novel, and thus stimulating, their content, the better. This is where vintage self-help lit proves superior to modern fare. No matter how original a contemporary author is, he or she is still filtering their ideas through the dominant paradigms and language of the present day. Even when a modern self-improvement book offers ideas that are fairly fresh, the overall tone inevitably feels very familiar. It doesn’t do much to wake up the mind.

Books from decades or a century back, however, feel quite a bit different. They come at things from different angles, use different idioms, strike a different tone. Whereas modern self-help literature tends to use analogies that compare human nature with technology (e.g., our brains are “hardwired”), old books use metaphors drawn from nature; whereas modern self-help lit often rests on insights from academic research (cue up the marshmallow study!), old books employ examples from the biographies of eminent individuals. Older books evince a different ethos as well: more sincere, more earnest, more concerned about overall character than simply becoming a worldly success.

Older self-help books deal with all the very same personal problems we have in our day, but without the diversions into evolutionary psychology and neuroscience (one wonders if knowing which area of the brain lights up when you act like a bonehead has ever prevented a single case of acting like a bonehead); without all the talk of anxiety and burnout and self-care; without all the endlessly regurgitated frameworks and shopworn buzzwords that may point to important issues, but which many people, ourselves included, feel so, so tired of hearing about.

This isn’t to say that all modern self-improvement literature is devoid of value; some worthwhile gems are still published from time to time. It’s just to say that if you want self-improvement books to improve you, you need to delve into literature that effectively shifts your mental models, and thus your behavior. And you’re more likely to find these sparks of inspiration in older books than in newer ones.

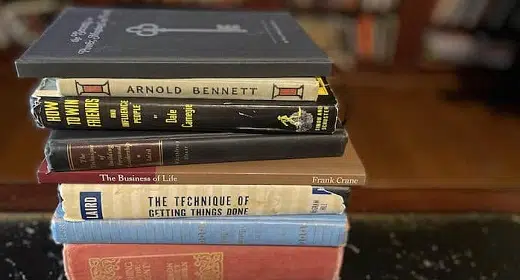

Below we suggest eight excellent places to start digging into the vast library of vintage self-improvement books. We’ve read a lot of them over the years, and these are the ones we most enjoyed and got the most from. As far as how we’re defining the “vintage” category here, we’ve arbitrarily set the parameters around books that were published from the 19th century up through the mid-20th. Books in this timeframe were written close enough to our own day to exhibit the style/format/content we now associate with self-improvement literature, while being far enough back in time to feel distinctly different.

These eight books have indirectly influenced our thinking, and directly inspired some of our work. In fact, we’ve published excerpts from many of these entries here on the blog, and turned distillations of the best nuggets from a couple of them into original books available in our store. But the source books are worth reading in their entirety too. Some of them are available in the public domain and can be read for free on sites like archive.org and Google Books. If you like hardback books, as we do, you can often find vintage copies on eBay and modern reprinted versions on Amazon (though be aware that such reprintings vary in the quality of their formatting).

Pushing to the Front by Orison Swett Marden (1894)

Orison Swett Marden was arguably the most influential forefather of modern self-help literature. Orphaned as a young boy, he credited reading a self-help book by Samuel Smiles with allowing him to keep his head above water and rise in the world. After becoming a successful hotelier, he added his own entry to the self-help canon — and helped create the future template for it — by penning Pushing to the Front. The book would be praised by the likes of Theodore Roosevelt, Henry Ford, and Thomas Edison and went through 250 printings in the 30 years after its publication.

While Marden would go on to pen 50 more books and booklets, his original outing is his best. Pushing to the Front is not our favorite on this list — it can be too over-the-top and bombastic with its exhortations. But the book is wonderfully bracing. It stirs you to work harder and lengthen your stride. Reading Pushing to the Front is like listening to a great coach give a rousing locker room speech. Simply for introducing us to the concept of “possibilities in spare moments” — an idea we continue to think about today — it’ll ever hold a place in our hearts.

How to Live on Twenty-Four Hours a Day by Arnold Bennett (1910)

As you look back on the last year, or decade, do you feel like you’ve merely been existing instead of truly living? Do you often go to bed at night with an anxious, sinking feeling that you wasted another precious day of your limited time here on earth? Arnold Bennett’s How to Live on Twenty-Four Hours a Day addresses this very concern better than anything else we’ve ever read. It describes and diagnoses the root of the problem and offers a program for overcoming it. Bennett has some very particular opinions about what should constitute this program, but you need not follow them to a T; the important part is committing to carving out some time each day to do things that will enrich your life and forward your progress.

This short little book — which we republished in its entirety here — only takes about 30 minutes to read and is so incisive and clever that it moves along very quickly and enjoyably. It’s truly just as relevant today as it was a century ago. As Bennett says, time is your most precious resource, and investing a half hour in reading his work will prove incredibly worthwhile.

The Writings of William George Jordan

William George Jordan (1864-1928) was an editor of literary journals and mainstream magazines who wrote a popular series of books on personal development: The Kingship of Self-Control, The Majesty of Calmness, The Power of Truth, and The Crown of Individuality. Each of these works consists of a collection of short essays on various subjects related to how an individual can reach his highest potential in mindset and character. Jordan delves into many existential, philosophical, and personal development themes that have re-emerged as popular principles in our own time, including Stoicism, simplicity, self-reliance, and the paramount importance of living truthfully. Unlike many modern authors, however, he doesn’t forward a vision of discipline and mastery that is focused solely on the self; instead, he also deals with an individual’s relations with family, friends, and community. He encourages the reader to improve his own life, in order to improve the lives of others.

Though each of Jordan’s books is a worthwhile read, not all of his essays are of equal strength, and some get a little redundant. For that reason, we created our own anthology — The Secrets to Power, Mastery, and Truth — of the very best essays across his works. Jordan is by far our favorite personal improvement writer of all time; his stuff is really good, and we truly, heartily recommend reading his books or picking up a copy of our anthology.

The Business of Living by Frank Crane (1916)

In his time, Frank Crane was a popular speaker, essayist, and columnist. He wrote a daily editorial that shared his observations on life and advice on success and happiness, which was syndicated in dozens of newspapers. The Business of Living is a collection of his greatest hits. While the entries can be a little hit or miss, there are plenty of gems in the book, including “The Ten Commandments of Success,” “Ten Things I Would Do If I Were Twenty-One,” “Advice to the Newly Married,” “The Love of Danger,” and “I Don’t Know.”

How to Win Friends and Influence People by Dale Carnegie (1936)

The classic of classic self-help literature. Since its publication in 1936, Dale Carnegie’s treatise on the principles of social success — How to Win Friends and Influence People — has sold over 30 million copies worldwide. Time magazine has listed it as one of the most influential books ever written.

How to Win Friends and Influence People remains so well-known and ubiquitous that it may be one of those books you feel you know all about (and maybe have written off) but have never actually read. In our podcast interview with Anna Schaffner, who’s researched the history and philosophy of self-improvement literature and read hundreds of books in the genre, she said that Carnegie’s book is the one that surprised her the most. While she expected it to be cheesy, she actually found it very incisive and useful. While she notes that Carnegie’s advice is somewhat Machivallean — you’re actively trying to influence folks to increase your personal power — the behaviors he suggests end up being win-wins for everyone; you get what you want from someone, but the person gets what they want as well — a chance to be recognized and feel good about themselves.

The Technique of Building Personal Leadership by Donald Laird (1944)

A professor of psychology, Donald Laird was the progenitor of a phenomenon we know very well today: an academic in the social sciences who writes accessible personal development literature for a popular audience. As with modern self-help literature, Laird often drew on his research and the research of fellow academics for the insights he offers in his books, especially those specifically aimed at business folks. But the advice he gives in one of his best books — The Technique of Building Personal Leadership — is largely based on anecdotes drawn from the lives of contemporary and historical figures.

Laird was also a progenitor of the writing style common to modern self-help lit — bullet point summaries, ample headings, numbered titles (e.g., “Five Ways to Build Personal Initiative”) — which makes his work very readable. As such, we’ve republished many of the chapters in The Technique of Building Personal Leadership here on the site; check out “The Vital Three Feet to Achievement,” “Poise That Makes One Master of Situations,” “Willpower Habits,” “How Moods Can Help Our Work,” “Personal Magnetism That Wins People,” and “How to Get Stick-to-itiveness.”

The Technique of Getting Things Done by Donald Laird (1947)

This is another worthy entry in what was Donald Laird’s extensive and popular oeuvre. It’s even heavier on the case studies from prominent people; the book primarily consists of very brief profiles of successful inventors, authors, scientists, executives, etc. (Some of which seem possibly embellished, but as Joseph Campbell said, “Myth is much more important and true than history.”) It’s refreshing to read tales of a time when improbable, rags-to-riches trajectories seemed more common, and when people actually made concrete discoveries; the story of someone tinkering with a new invention in their basement laboratory is just somehow more exciting than someone writing code on a laptop in their dorm room. Interspersed amongst the case studies are practical bits of advice for being effective in the world. For a taste of the book, try “The Power of Pocket Pads,” “How to Decide Trifles Quickly,” and “A Place for Everything (Including Certain Kinds of Work).”

The Mature Mind by H.A. Overstreet (1949)

“It will mean much to our confused and hostility ridden world if and when the conviction begins to dawn that the people we call ‘bad’ are people we should call immature. This conviction would bring us to the realization of what needs to be done if our world is to be rescued from its many defeats. The chief job of our culture is, then, to help all people to grow up.”

So the psychologist Harry Allen Overstreet argues in The Mature Mind. In the book, he makes the case that maturity is the foundation for both a healthy society and individual fulfillment, and dives into what it means to be mature. Overstreet unpacks the traits, behaviors, and mindsets which move an individual from the inward-focused egocentricity of childhood to the outward-directed stance of adulthood — from dependence to independence, incompetence to efficacy, bewilderment to wisdom.

Along with his wife Bonaro, Overstreet also wrote a related and worthy read: The Mind Alive. For a distillation of some of the best bits from both books, check out The 33 Marks of Maturity, a short ebook we wrote which drew from and was inspired by the Overstreets’ ideas.