by James DeGregori: Principles of evolution and natural selection drive a radical new approach to drugs and prevention strategies…

This year at least 31,000 men in the U.S. will be diagnosed with prostate cancer that has spread to other parts of their body, such as bones and lymph nodes. Most of them will be treated by highly skilled and experienced oncologists, who have access to 52 drugs approved to treat this condition. Yet eventually more than three quarters of these men will succumb to their illness.

Cancers that have spread, known as metastatic disease, are rarely curable. The reasons that patients die despite effective treatment are many, but they all trace back to an idea popularized in 1859 by Charles Darwin to explain the rise and fall of species of birds and tortoises. Today we call it evolution.

Think of a cancer cell like Darwin’s Galápagos finches, which had slightly different beaks on various islands. Finches eat seeds, and seeds on each island had different shapes or other characteristics. The bird with a beak shape best matched to the local seed got the most food and had the most offspring, which also had that particular beak shape. Birds with less adaptive beaks did not make it. This natural selection ensured that different finch species, with various beaks, evolved on each island. The key is that when two groups of critters compete in the same small space, the one better adapted to the environment wins out.

Cancer cells evolve in a similar manner. In normal tissue, regular noncancer cells thrive because they are a good fit for the biochemical growth signals, nutrients and physical cues they get from surrounding healthy tissue. If a mutation creates a cancer cell poorly adapted for those surroundings, it does not stand much chance initially: normal cells outcompete it for resources. But if the surroundings are further damaged by inflammation—sometimes a growing cancer can cause this itself—or old age, the cancer cell does better and starts to outcompete normal cells that used to crowd it out. The change in the surroundings ultimately determines a cancer cells’ success.

This is a theory we call adaptive oncogenesis, and we have found evidence that supports it in the way cancer takes off when we change its cellular environment in experimental animals, although the internal workings of the cancer cell have not changed. Doctors have also observed this acceleration of cancer in humans with tissue-disturbing ailments such as inflammatory bowel disease. The overall implication is that we can best understand cancer by looking at its surroundings rather than solely focusing on the mutations inside a cell. By reducing tissue alterations caused by processes such as inflammation, we can restore a more normal environment and—as we have shown in animal studies—prevent cancer from gaining a competitive edge.

Our evolutionary perspective also has inspired a different approach to cancer therapy, one that we have successfully tested in small clinical trials. Doctors dump a lot of chemotherapy drugs on a cancer in an effort to kill every last trace of the threat, and at first this often looks like it works. The tumor shrinks or goes away. But then it comes back and is resistant to the drugs that once killed these cells, akin to crop-destroying insects that evolve resistance to pesticides. In a clinical trial with prostate cancer patients, one of us (Gatenby) tried an alternative to the scorched-earth approach, applying only enough chemo to keep the tumor tiny without killing it entirely. The goal was to maintain a small population of vulnerable chemosensitive cells. That population did well enough to prevent cells with an unwanted new trait—chemoresistance—from taking over. In a group of patients in which tumors usually start growing uncontrollably after 13 months, this regimen has kept tumors under control for 34 months on average—with less than half the standard drug dose.

The results of our prevention and therapeutic strategies may point to a way to ward off cancer before it becomes a danger to life and limb and to save many patients for whom a regimen of giant, toxic drug doses has failed.

WHY DO WE GET CANCER?

If you asked almost any doctor or cancer researcher, “Why is aging, smoking or radiation exposure associated with cancer?” you would probably get a short answer: “These things cause mutations.” This assessment is partly true. Exposure to cigarette smoke or radiation does cause mutations in our DNA, and mutations do accumulate in our cells throughout life. The mutations can provide cells with new properties, such as hyperactive growth signals for cell divisions, reduced death rates or even an increased ability to invade surrounding tissue.

Yet this simple explanation, focused on changes within cells, overlooks the fact that a major driver of evolutionary change in any single cell—or in entire collections of them, such as human beings—is outside, in the cell’s environment.

.png)

We know that the evolution of species on the earth has been highly dependent on environmental perturbations, including dramatic changes to landmasses, the gases in the air and water, and ambient temperature. These changes led to selection for new adaptive features in organisms, producing amazing diversity. As Darwin wrote in On the Origin of Speciesin 1859, “Owing to this struggle for life, any variation, however slight and from whatever cause proceeding, if it be in any degree profitable to an individual of any species, in its infinitely complex relations to other organic beings and to external nature, will tend to the preservation of that individual, and will generally be inherited by its offspring” (emphasis added). Darwin proposed that competition for limited resources would drive selection for individuals with traits that were best adapted to the environment. And when environments changed, so would these pressures, selecting for new traits that were better tuned to the new surroundings.

Similar Darwinian dynamics should apply to the evolution of cancers in our body. Even though we trained as a molecular biologist (DeGregori) and a physician (Gatenby), evolution and ecology have always fascinated both of us. Our extensive reading in these areas, while initially driven by what we thought was curiosity unrelated to our day jobs, revealed unappreciated parallels between the driving forces of evolution and our observations of cancer development and cancer patients’ responses to therapy.

For instance, cancer researchers typically believed that a cancer-causing mutation would always confer an advantage to a cell that acquired it, but we recognized a classic evolutionary principle at work: A mutation does not automatically help or hinder an organism. Instead its effects are dependent on features of the local environment. In Darwin’s finches, there is no “better” beak shape per se, but certain beaks improve survival under certain conditions. Similarly, we reasoned that a mutation that turns on a cancer-causing gene does not provide an inherent advantage to the cell and can, in fact, be disadvantageous if it makes that cell less able to use the resources of the tissue immediately around it.

We were also inspired by the punctuated equilibrium theory of paleontologists Niles Eldredge and Stephen Jay Gould, who noted that species often maintain stable traits through millions of years of fossil records, only to suddenly evolve rapidly in response to a dramatic environmental change. This concept stimulated our ideas about the way that some tissues could be initially unfavorable to cell mutations, but changes in those tissues, such as damage and inflammation in a smoker’s lungs, could stimulate evolutionary change—sometimes leading to cancer.

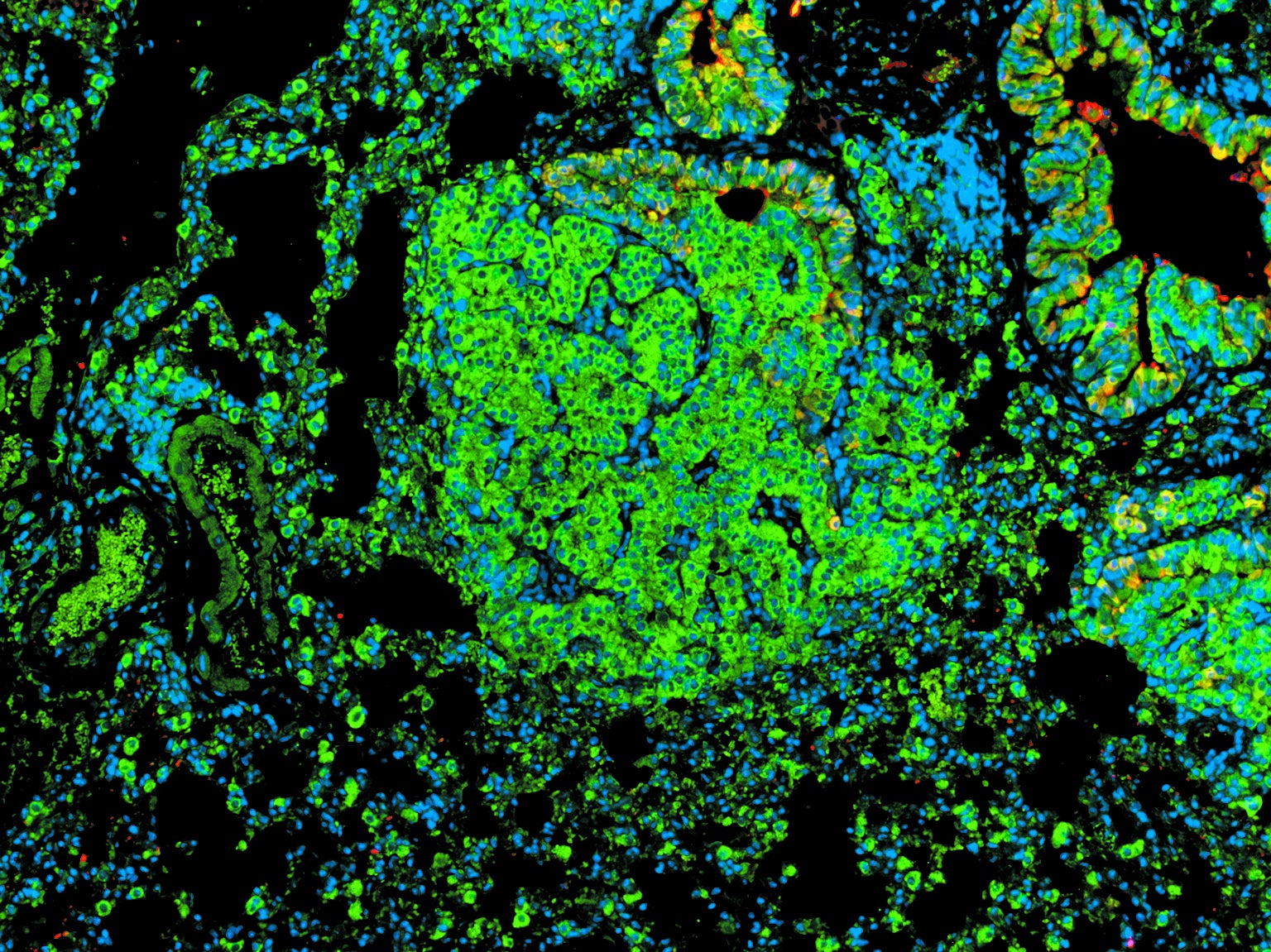

We first saw this dynamic at work with aging-associated changes in bone marrow that led to the development of leukemias. Working with groups of young and old mice in DeGregori’s Colorado lab, Curtis Henry, now at Emory University, and Andriy Marusyk, now at the Moffitt Cancer Center, created the same cancer-causing mutations in a few of the mice’s bone marrow stem cells. The results showed that the same cancer-causing mutations can have very different effects on the fate of these cells, depending on age: the changes promoted the proliferation of mutated cells in the old mice but not in the young ones. And the determining factor did not appear to be in the mutated cells but in the metabolism and gene activity of the normal cells around them. For example, the activity of genes important for stem cell division and growth was reduced in nonmutated stem cells in the bone marrow of old mice, but it was restored in these cells when we introduced the cancer-causing mutation. Yet the mutation that helped these cells had bad effects on the mice. These stem cells normally generate key players in the body’s immune system, but the population explosion of the cancer-mutated version of the cells instead led to the development of leukemias.

On the other hand, the fit young stem cells in the tissues of a young mouse already had levels of growth and energy use that nicely matched what their surroundings could provide. Therefore, such cells did not benefit from the cancer-causing mutations when we introduced them. The mutated cell populations did not grow. By favoring the status quo, youth is tumor-suppressive.

Why does any of this matter? Although we can avoid some mutations by not smoking and keeping clear of other mutagenic exposures, many, if not most, of the mutations that we accumulate in our cells during life cannot be dodged. But this new focus on tissue environments introduces a way to limit cancer: reversing tissue alterations caused by aging, smoking and other insults will reduce the success of cancer-causing mutations. The mutations will still occur, but they will be much less likely to give cells an advantage and thus will not grow in number.

Of course, there is no Fountain of Youth to reverse or prevent aging. Doing the things we know we should, such as exercising, eating a balanced diet and not smoking, can improve the maintenance of our tissues, which may be the best strategy we can use for the moment. But if we can figure out what key tissue environmental factors favor cancer development, we should be able to change these factors to limit malignancies. Indeed, in our mouse experiments, we showed that when we reduced the activity of inflammation-causing and tissue-damaging proteins in old mice, cells with the cancer-causing mutations did not proliferate; normal cells maintained their dominance. But we must proceed cautiously. Blocking inflammation in mice living in sterile cages may reduce cancer, but a similar strategy in people in the real world could limit defenses against infections because inflammation is part of our immune response.

FROM PREVENTION TO THERAPY

In addition to primary prevention, an evolutionary understanding can help make therapies for existing cancers more effective by reducing the nasty tendency of such cells to develop drug resistance. The evolution of resistance happens in other realms. Perhaps the most familiar example is the centuries-old contest between farmers and crop-destroying insects. For more than a century pesticide manufacturers produced a steady stream of new products, but the pests always evolved resistance. Eventually manufacturers recognized that trying to eradicate the pests by spraying high doses of pesticides on fields was making the problem worse because of an evolutionary process termed competitive release.

To understand competitive release, remember that all the insects within a large population occupying a field are continuously competing with one another for food and space, and they are not identical (as is also the case for cancer cells). In fact, for nearly every trait, including sensitivity to a pesticide, there is inevitable variability within a population. By spraying a large amount of insecticide (or administering a large dose of chemotherapy), the farmer (or oncologist) may kill the vast majority of insects (or cancer cells). Yet a few insects (or cells) have traits that make them less vulnerable, and with the highly vulnerable organisms removed, the resistant ones begin to spread. A farming strategy called integrated pest management tries to deal with this situation by using pesticides sparingly. Rather than trying to eradicate the pests, farmers spray only enough to control them and lower crop damage without resulting in competitive release. In this way, sensitivity of the pest to the pesticide is maintained.

The medical community has learned a similar lesson with antibiotics: excessive use must be stopped to curtail the constant evolutionary cycle that produces the development of drug-resistant pathogens. But this lesson has not yet taken hold in the cancer field.

Like farmers who used to blast fields with huge amounts of insecticides, doctors today typically give chemotherapy to patients at “maximum tolerated dose (MTD) until progression.” Nearly all cancer drugs also damage normal tissues in the body, and these side effects can be very unpleasant and even fatal. MTD means the drugs are given in amounts that fall just short of killing the patient or causing intolerable side effects. Giving the same treatment “until progression” emerges from a traditional metric of treatment success, based on the tumor’s change in size. Drugs are deemed successful when the tumor shrinks, and the treatment is abandoned if it gets bigger.

To most patients and doctors, treatment designed to kill the maximum number of cancer cells with relentless administration of the greatest possible amount of lethal drugs feels like the best approach. But as in the control of insects and infectious diseases, this strategy, in the setting of an incurable cancer, is often evolutionarily unwise because it sets in motion a series of events that actually accelerate the growth of drug-resistant cancer cells.

The other evolutionary lesson learned from pest control is that a “resistance management plan” can keep unwanted populations in check, often indefinitely. Can this strategy also lead to better outcomes for patients with incurable cancers? The answer is not yet clear, but there are hints from experimental studies and early clinical trials that it could do just that.

An evolution-based strategy for a patient who, after a month on an anticancer drug, had a 50 percent reduction in tumor size would be to stop treatment. This approach would be used only when we knew from past experience that available treatments—chemo, hormone therapy, surgery, immune system boosters—could not cure the cancer in this patient. Because a cure would not be achievable, the goal would instead be to keep the tumor from growing and metastasizing for as long as possible. By stopping therapy, we would leave behind a large number of treatment-sensitive cancer cells. The tumor would then begin to grow back and eventually reach its previous size. Yet during this regrowth period, because no chemotherapy would be administered, the majority of tumor cells would still be sensitive to the anticancer drug, not resistant to it. In effect, we would use the sensitive cells that we could control to suppress the growth of the resistant cells that we could not control. As a result, the treatment would be able to maintain tumor control much longer than the conventional approach of continuous administration of maximum dose and, because the drug dose would be significantly reduced, with much less toxicity and better quality of life.

Gatenby’s lab began by investigating the approach in 2006 using mathematical models and computer simulations. Although such models had rarely been employed in cancer-treatment planning, the large number of possible treatment options required us to adopt an approach, common in physics, in which mathematical results help to define experimental methods that are likely to be successful. Our models defined the levels of drugs we wanted to test. The next step was to try those doses in mouse experiments, and doing so confirmed that tumor control could be greatly improved by evolution-based strategies.

The results were good enough to prompt a move into the clinic and a test on human cancer patients. We were joined in this effort by Jingsong Zhang, an oncologist at the Moffitt Cancer Center, who treats men with prostate cancer. With the help of Zhang, along with mathematicians and evolutionary biologists, we developed a model of the evolutionary dynamics of prostate cancer cells during treatment. We used this model to simulate the responses of prostate cancer to a variety of drug doses administered by an oncologist. Then we ran these encounters over and over again until we arrived at a series of doses that kept the cancer in check for the longest time without increasing the population of drug-resistant cells.

Next we asked patients with aggressive prostate cancer that had already metastasized to other locations—the kind that doctors cannot completely eliminate from the body—to volunteer for a clinical trial. So far the patients have had excellent outcomes. Of the 18 people enrolled, 11 are still in treatment. Standard therapy typically maintains control of metastatic prostate cancer for an average of about 13 months. In our trial, average tumor control is at least 34 months, and because more than half of our patients are still being treated actively, we cannot yet place an upper limit on how well they do. Furthermore, this control is being achieved using only 40 percent of the drug dose that patients would have received in standard treatment. But it is still early days for this treatment approach. Just because it works in prostate cancer does not mean it works in stomach cancer, for instance. And it may be tough to convince patients, even those with an incurable disease, that the best approach is not to kill as many cancer cells as possible but as few as necessary.

THE RULES OF CANCER

In many ways, the evolutionary model of cancer development and treatment serves to dispel the “mystery” of cancer. The proclivity of the disease to strike without any clear cause, along with its ability to overcome and return even after highly effective and often highly toxic therapy, can be viewed by patients and caregivers as both hopelessly complicated and magically powerful. In contrast, understanding that cancer obeys the rules of evolution like all other living systems can give us confidence that we have a chance to control it. Even without a cure, by using our understanding of evolutionary dynamics, we can strategically alter therapy to get the best possible outcome. And prevention strategies can be geared toward helping to create tissue landscapes in the body that favor normal cells over cancer cells.

For more than a century the cancer research community has sought “silver bullets”—drugs that can eliminate all cancer cells while sparing all normal cells. Cancer has been taking advantage of evolution to sidestep these drugs. But we can use evolution, too. We have the opportunity to expand the work of Darwin and his successors to develop more realistic approaches to both prevent and tame this deadly disease.