by Matthew Hutson: What to know about what you don’t know you know…

In 1997, IBM’s Deep Blue supercomputer beat the world’s best chess player, Gary Kasparov. Immediately, some people noted that we were still superior at the ancient Chinese game of Go. Go, they reasoned, would remain out of robots’ reach for the foreseeable future. Its plurality of possible moves and the nuances in evaluating even who’s winning put it further out of the realm of rote combinatorics and into the orbit of intuition, supposedly humanity’s specialty. “It may be a hundred years before a computer beats humans at Go,” a Princeton astrophysicist told The New York Times soon after the Kasparov match. “Maybe even longer.” If you follow the news, you know it took until 2016.

What does the success of DeepMind’s AlphaGo against the best meat-based players say about intuition, human or otherwise? On one hand, it knocks down some highfalutin’ claims about this special sense, revealing it to be, as some psychologists have long held, nothing more than pattern recognition.

On the other, “pattern recognition” does not do full justice to the many patterns intuition recognizes. Most of human behavior happens automatically, guided by genetics and habit rather than conscious deliberation. “You could not get by if you walked into a restaurant and you had to reconstruct from first principles how to behave,” says Valerie Thompson, a psychologist at the University of Saskatchewan in Canada.

Even for more complex problems, intuition drives decisions, says Gerd Gigerenzer, a psychologist at the Max Planck Institute for Human Development in Berlin. In working with top executives at the largest German firms, he finds that “they go through all the data they have—and they’re buried under data—and at the end the data don’t tell them what they should do.” Intuition, he says, “is a form of unconscious intelligence that is as needed as conscious intelligence.”

Despite intuition’s ubiquity, we harbor many mistaken intuitions about intuition. Here we’ll consider eight facets of unconscious processing—including its application to creativity, morality, and social interaction—looking at what it does well, where it fails, who uses it, when we trust it, and how to improve it. Building Deep Blue and AlphaGo required a lot of hard, deliberate thought, but it also required loads of human intuition and insight. The fact that we hacked together machines to beat us in a couple of small corners of our own game proves, if nothing else, that we can hack our own intuitions, too.

1. Intuition Is Highly Efficient—if You Don’t Think About It Too Much

A body of research reveals that intuition can be not only faster than reflection but also more accurate.

We’re fairly good at judging people based on first impressions, thin slices of experience ranging from a glimpse of a photo to a five-minute interaction, and deliberation can be not only extraneous but intrusive. In one study of the ability she dubbed “thin slicing,” the late psychologist Nalini Ambady asked participants to watch silent 10-second video clips of professors and to rate the instructor’s overall effectiveness. Their ratings correlated strongly with students’ end-of-semester ratings. Another set of participants had to count backward from 1,000 by nines as they watched the clips, occupying their conscious working memory. Their ratings were just as accurate, demonstrating the intuitive nature of the social processing.

Critically, another group was asked to spend a minute writing down reasons for their judgment, before giving the rating. Accuracy dropped dramatically. Ambady suspected that deliberation focused them on vivid but misleading cues, such as certain gestures or utterances, rather than letting the complex interplay of subtle signals form a holistic impression. She found similar interference when participants watched 15-second clips of pairs of people and judged whether they were strangers, friends, or dating partners.

Other research shows we’re better at detecting deception and sexual orientation from thin slices when we rely on intuition instead of reflection. “It’s as if you’re driving a stick shift,” says Judith Hall, a psychologist at Northeastern University, “and if you start thinking about it too much, you can’t remember what you’re doing. But if you go on automatic pilot, you’re fine. Much of our social life is like that.”

Thinking too much can also harm our ability to form preferences. College students’ ratings of strawberry jams and college courses aligned better with experts’ opinions when the students weren’t asked to analyze their rationale. And people made car-buying decisions that were both objectively better and more personally satisfying when asked to focus on their feelings rather than on details, but only if the decision was complex—when they had a lot of information to process.

Intuition’s special powers are unleashed only in certain circumstances. In one study, participants completed a battery of eight tasks, including four that tapped reflective thinking (discerning rules, comprehending vocabulary) and four that tapped intuition and creativity (generating new products or figures of speech). Then they rated the degree to which they had used intuition (“gut feelings,” “hunches,” “my heart”). Use of their gut hurt their performance on the first four tasks, as expected, and helped them on the rest. Sometimes the heart is smarter than the head.

2. We Get Too Deeply Attached to Intuitive Beliefs

Once an intuition hits, we cling to it despite the dangers. Intuition can, for example, lead to all sorts of cognitive and social biases, like the anchoring effect (where decisions are swayed by the first piece of information thrown at us) and racial prejudice. Even in areas where the heart should rule, like romance, it can be clueless. In a classic study, when men on a bridge were stopped by an attractive woman and asked to complete a questionnaire, they were more likely to try to contact her afterward if it was a scary suspension bridge, misattributing emotional arousal to sexual attraction.

Our dreams, those unwilled visions of the night, hold a powerful aura of truth we can’t quite extinguish. People report they’re more likely to change their travel plans if they dreamed about a plane crash than if the government announced an actual travel warning. And test-takers can’t shake the “first instinct fallacy.” Three in four college students reported that when reconsidering an answer on an exam, their initial choice will usually turn out to be correct. But when erase marks on actual exams were analyzed, the reverse was true: Twice as many changed answers went from wrong to right as right to wrong.

“In general,” says psychologist Sascha Topolinski of the University of Cologne in Germany, “intuition is something emotional that makes you confident in an idea. ‘You cannot take away this feeling from me. I do not trust this car seller. I can’t tell you why, but I’m confident I don’t like him.’”

Intuition about the accuracy of an intuition is even more fallible. When people were asked to rate their confidence that their “gut feelings” had steered them skillfully on a test, confidence ratings had no relationship with actual performance.

Even when we acknowledge the absurdity of an intuition, we often stick with it. Consider superstitions. I’m an atheist who knocks on wood while knowing it’s hogwash. “When an intuition captures attention and triggers emotions, it may be especially hard to shake,” says Jane Risen, a psychologist at the University of Chicago. She calls maintaining beliefs we know to be false “acquiescing to intuition.” Intuition may not be magic, but we are truly under its spell.

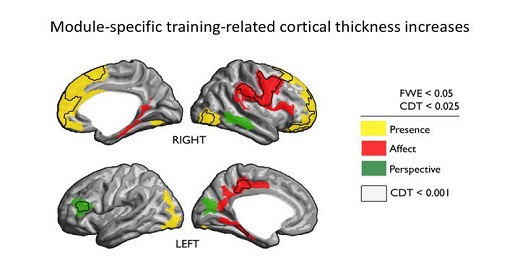

3. Intuition Can Be Improved—With Practice

To have good intuitions in any domain requires a lot of practice. But not all domains are amenable to good intuitions. First, there must be regularities linking events and outcomes—the domain must have high “validity.”

Gary Klein, a psychologist at the Washington, D.C., consulting firm MacroCognition, has long explored the role of wisdom in the intuition of experts such as fire commanders, who can size up a burning building quickly. “Fires follow the laws of physics,” says Klein.

The global economy is significantly more chaotic, preventing predictability. (As Gigerenzer notes, five years before the 2007 housing crisis, the president of the American Economic Association said, “Macroeconomics…has succeeded. Its central problem of depression prevention has been solved.”)

Whether you should trust your feelings should hinge not on the strength of those feelings—we have poor intuitions about intuitions—but on the structure of the domain you’re operating in. Look outward, not inward.

Second, you need clear feedback to hone your intuitive decisions. A review of the literature shows that weather forecasters, test pilots, and chess masters had more reliable expertise than psychologists, admissions officers, and judges. Outcomes in the latter’s areas are fuzzier and can play out long after you’ve made a decision. That goes for much of everyday life, too.“You don’t do a diary and an Excel file where you write, ‘Okay, on October 1, I made this decision, or I bought this product,’ and so on,” Topolinski says. We lack hard data about what we do.

Good intuitions in one domain don’t guarantee good intuitions in another. As Gigerenzer puts it, “A soccer player who has great intuitions about scoring a goal may have bad intuitions about spending his money. So there cannot be a general test of intuition.” Even within a domain, expertise can vary between different kinds of tasks.

We can use focused thinking not only to train our intuitive expertise over time but also to invite or avoid intuitions in the moment. Metaphors and sketches are excellent tools to help us reframe problems or see solutions more clearly.

Klein coaches people to consider premortems: When considering a plan, imagine from a future vantage point that it failed and think about what went wrong. This thinking tool makes weak points real—intuitive objects rather than abstract and ignorable hypotheses.

Philosopher Daniel Dennett of Tufts University has coined the term intuition pumps for thought experiments meant to reframe problems. But he notes that they can be used for good or for evil.

“One should learn how easy it is to build bogus intuition pumps that will provoke fist-pounding intuitions that aren’t worth your allegiance,” Dennett says. “But also, intuition pumps can help you out of imagination blockades. Caution is advised.”

The role of deliberation in honing instincts and knowing when to trust them reveals reflection’s close collaboration with intuition, in both its development and deployment. “Our reflective deliberation scaffolds off our intuition, but it goes both ways,” says psychologist Gordon Pennycook of the University of Regina in Canada. We also tend to use them in tandem.

4. Intuition Is Sensing; Insight Is Seeing

Intuition is closely related to another I word, insight. Sometimes the two are conflated, which is understandable. Both relate to realizations emerging from subconscious processes, offering guidance and hiding their tracks. But they’re fundamentally different.

“Insight is about seeing,” says Eugene Sadler-Smith, a management researcher at Surrey Business School in England. “You can articulate the solution, and you can explain it to someone else.” Whereas intuition is sensing: “We can sense a solution to a problem, or we can sense a decision that we should take. It’s a judgment—it’s almost like a hypothesis. We don’t know whether it’s right or wrong until we act on it.”

According to MacroCognition’s Gary Klein, “Intuition is how we use our experience to know how to act. Insight runs in the opposite direction. It’s not just drawing on what you know. It’s changing what you know.”

To that end, we sometimes need to clear intuition out of the way to obtain the sudden solutions we call insight. Breakthroughs are often counterintuitive. One way to demonstrate the role of habitual hindrances is to look at magic tricks. Illusions work through mental jujitsu, using our assumptions against us. To discover how a trick is done, one must relax certain mental constraints—a good tactic for eliciting insights in general.

In one study, participants watched video clips of a dozen magic tricks, and half received a verbal clue directing their attention to an assumption. For example, when the magician appeared to throw a coin from one hand to another before making it disappear, the clue was “transfer to other hand.” Given such prods to counter their intuition about what they saw, their solution rate went from 21 percent to 33 percent.

Intuition’s relationship with insight is complicated. It can sometimes indicate when an insight is possible. A common laboratory test of insight is the remote associates test (RAT): Given three words, such as cottage, swiss, and cake, can you find a fourth that connects them? (In this case, cheese.) A variation on this task shows people either a coherent or a random word triad and makes them guess quickly whether it’s solvable before asking them for a solution. Even in cases where people can’t summon the solution, they’re better than chance at judging the triad’s coherence.

Scientists use creative intuition to select which paths to follow toward potential discoveries. “This is this idea of sensing the right direction,” Sadler-Smith says, “like a radar that says ‘Go down there, but not down there.’” Nobel laureates have discussed their use of hunches. Michael S. Brown (Medicine, 1985), has said, “As we did our work, I think, we almost felt at times that there was almost a hand guiding us.”

But we tend to have poor intuition about how close we are to an insight. In one study, participants were given math and logic problems, whose solutions required either a central insight or mere grinding, and were asked to estimate their distance from the solution every 15 seconds. Unlike for the non-insight problems, estimates for insight problems remained fairly flat until the final “Aha!”

In a second study, participants’ predictions of whether they’d be able to solve insight problems had no correlation with the truth, unlike for routine algebra problems. Topolinski notes the age-old attempt to perform a mathematical feat called “squaring the circle” before it was proved impossible in 1882. “There were many blind tracks that people followed for millennia,” he says. Similarly, Einstein produced his theories of relativity, “then for the rest of his life he’s concocting a possible theory of everything.” Such a theory may be out there, but “for his capabilities and his time, this was a wrong intuition.”

5. Stress Favors Intuition; Sadness Doesn’t

Deliberation is a luxury. In dire situations—say, while being chased by a bear—you don’t have time to weigh all your options. You follow your first instinct (run, presumably). Anxiety engendered in any situation similarly pushes you toward fast and frugal reflexes. If you’re truly in danger, that can be handy. Otherwise, reflection might be better.

One study looked at the effects of stress on decision-making by attaching electrodes to participants’ hands and randomly zapping them. Meanwhile, the poor souls had to complete analogies by flipping through answers one at a time: “Butter is to margarine as sugar is to…beets, saccharine, honey, lemon, candy, chocolate.” Compared to participants who didn’t receive shocks, they were more likely to jump on an answer without even viewing all the options and, as a result, got more wrong.

Stress’s effects on the brain are mediated in part by the release of the hormone cortisol. In one experiment, researchers gave participants a cortisol-increasing drug or a placebo, then had them do something called the cognitive reflection test (CRT). The CRT consists of three questions, each with an intuitive but wrong answer. For instance, “A bat and a ball cost $1.10. The bat costs $1.00 more than the ball. How much does the ball cost?” You want to say 10 cents, but a quick calculation reveals the ball is 5 cents and the bat is $1.05. Most people, even students at elite colleges, fail to get all three problems right, but cortisol reduced correct answers even further.

Even as stress triggers heuristic thinking—habits and short-cuts—it degrades more sophisticated intuitive processing. Remember the remote associates test (cottage, swiss, cake)? One study found that increasing anxiety in participants by showing them hair-raising images scrambled their intuitions about whether a connecting word existed.

The morbid images may have affected this performance measure, called an intuition index, in part by lowering participants’ mood. Sadness tends to make people think analytically. We’re sad when something’s wrong, which may be time for focused problem-solving.

6. Some People Are More Intuitive Than Others

Some researchers believe there are individual differences in broad intuitive ability. A recent study found two clusters of intuitive skill. One is related to insight—such as conceiving a new metaphor—which is linked to intelligence. The other, related to implicit learning, or learning complex information without being aware of what you’ve learned—say, picking up a new language—is not strongly linked to intelligence.

Perhaps more consequential for behavior than general intuitive ability is thinking style—the degree to which you rely on intuition and reflection in the first place. A common measure in research is the Faith in Intuition (FI) scale, in which people rate agreement with statements like “I believe in trusting my hunches.” FI and similar measures have been linked with several positive characteristics. People with high FI receive high intuition index scores—as long as they’re in a positive mood, a state that brings intuition out to play.

Another scale, with items like “I generally make decisions that feel right to me,” correlated with better recognition of social norms, as measured by how accurately people estimated their peers’ acceptance of behaviors likes stealing and fighting. And another correlated with greater creativity on several tasks such as drawing and thinking of uses for a cardboard box.

But people who put faith in intuition also pay a price. They perform worse on tasks requiring logic. They report having experienced more setbacks resulting from poor decisions, ranging from missing a flight to getting divorced. They report greater magical thinking—belief in astrology, ghosts, luck, God, and so on. And in one study, they were more likely to stereotype based on gender (but only in a positive mood).

Topolinski suggests that people might want to seek careers that match their thinking style. An accountant won’t get as far relying on her gut as would, say, a counselor. And in any profession, if you know you put great faith in feelings, you might make room for extra reflection on tasks where snap decisions can get you into trouble, like getting to the airport.

7. Morality Intuitions Are Easily Swayed

Some of our deepest-held beliefs involve morality, how we feel people should behave toward one another. And although they may seem as rock-solid as fact—Thou shalt not kill—they’re just as guided by intuition as anything else.

We can reason about many of them, but only to a point. For many, especially on controversial or subtle issues like abortion, it comes down to intuition: It just feels wrong (or right).

Moral intuitions are unavoidable and also valuable, says psychologist Matthew Feinberg of the Rotman School of Management in Toronto. They drive kindness as well as social justice movements. “But moral intuitions are also at the heart of many, many problems in society.” Impassioned gut reactions can derail rational discussion, as opponents are labeled evil.

Many findings highlight the unconscious processing built into moral judgment. Often we base opinions on things we’d never factor into a deliberate decision. In one study, participants’ approval of sex between cousins depended on whether someone had secretly deployed fart spray nearby. Visceral repulsion led to moral repulsion.

In another study, participants were asked whether it was okay to push a large man off a footbridge to block a trolley from killing five other people. If they’d just watched a clip from Saturday Night Live, versus a documentary, their mood was more positive, and they were four times as likely to approve. This does not sound like reflection: Thou shalt not kill—unless you’ve heard a good joke lately.

Of course, morality is based on more than fleeting incidental cues. We also have deeper values like fairness and loyalty, each an abstraction formed from a lifetime of experience. Psychologist Jonathan Haidt of New York University has delineated five distinct “moral foundations” that guide our behavior: fairness, loyalty, authority, purity, and avoiding harm. Studies suggest that political liberals prioritize fairness and harm avoidance; conservatives favor loyalty, authority, and purity.

And Feinberg has found that we can shape people’s moral intuitions by catering messages to their preferred values. When he framed an argument for universal health care in terms of purity (fewer diseased Americans) versus fairness (health care for all), conservatives expressed more support for Obamacare. When he framed an argument for military spending in terms of fairness (fighting inequality) versus authority (American supremacy), liberals expressed more support.

Likewise, he swayed conservatives to support same-sex marriage through loyalty (patriotic couples) and environmentalism through purity (a clean planet). He also used moral reframing to reduce conservative support for Donald Trump (he disloyally dodged the draft) and liberal support for Hillary Clinton (she unfairly favors Wall Street).

Examples, metaphors, images, and stories can give shape to our own and others’ intuitions not only in politics but in all realms of life: science, relationships, education. We gain new models of the world, and thought—conscious and not—fills them in.

As for messages meant to elicit gut reactions, “We see a lot of that on the Internet these days,” says the University of Saskatchewan’s Thompson. “Memes. That’s exactly what they are.” One could fairly call memes the fart spray of the internet.

8. You Can Read People by Reading What They Write Online

Humans have strong intuitions about other people. That’s because character judgment has such dire consequences, and because we have so much experience with it, over our lifetimes and over evolution. What happens when people-reading goes online? And when it’s limited to the reading of what others write? Increasingly, we must assess each other via snippets of text, rather than, say, darting eyes or kind smiles, but that doesn’t hold back our snap judgments.

Generally, when asked to rate a writer’s personality traits based on emails, personal essays, streams of consciousness, mock diary entries, mock blog posts, Twitter feeds, and dating ads, readers agree with each other more than chance would allow, indicating that there are cues in written reports that reliably trigger our intuitions. Which cues do we use?

In dating profiles, studies show, swear words suggest high neuroticism and low conscientiousness and agreeableness. Angry words suggest the same in tweets. In personal essays, exaggeration suggests extraversion and openness to experience. Past tense suggests depression in blog posts, and cognitive words like know suggest it in diaries. Surely deliberation plays a role in judgments, but I doubt anyone is counting past-tense verbs.

Our judgments about traits from writing samples are also frequently more accurate than chance would allow. And some people are better than others at reading between the lines. One study, by Hall of Northeastern University, found that the best judges were female, agreeable, conscientious, emotionally stable, compassionate, interested in others’ lives, and big readers, especially of fiction.

Judgments of personality can come from the thinnest of slices—even just an email address. What’s thinner than an email address? Punctuation. A study found that angry- and happy-seeming emails have many exclamation points and few question marks, and feminine-seeming emails have both. Other work found that smileys in formal emails don’t make the writer seem warm but do make him or her seem incompetent. Meanwhile, adding a smiley with a nose to a dating profile will win more replies, while adding a noseless smiley will get you fewer ;-). To think, your future may depend on an emoji.

Neither head nor heart can survive on its own, and negotiating their symbiosis is a challenge that’s much harder than mastering chess or Go. “‘It’s not about whether intuition or analysis is best,’” Sadler-Smith tells managers. “The real skill in decision-making, problem-solving, creativity, whatever, is blending those two things together. And in a way that’s kind of a lifetime project, isn’t it?”