A new study using the nematode worm C. elegans indicates that vitamin D works with longevity genes to increase lifespan and prevent the accumulation of toxic proteins linked to age-related chronic diseases…

A new study indicates that vitamin D has much wider effects on the body than previously realized, and that the vitamin is deeply associated with many aging-related ailments. The work was conducted with the nematode worm, C. elegans. Research at the Buck Institute for Research on Aging shows that vitamin D works through genes known to influence longevity and impacts processes associated with many human age-related diseases.

The study, which was published in recently in the journal Cell Reports, may help explain why vitamin D deficiency has been linked to breast, colon and prostate cancer, along with as obesity, heart disease and depression.

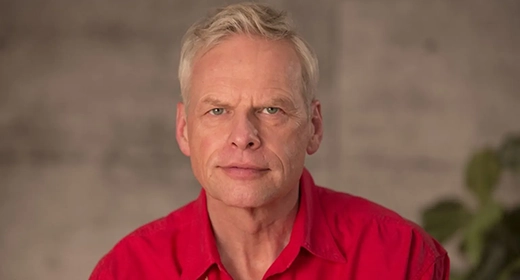

“Vitamin D engaged with known longevity genes – it extended median lifespan by 33 percent and slowed the aging-related misfolding of hundreds of proteins in the worm,” said Gordon Lithgow, the study’s senior author. “Our findings provide a real connection between aging and disease and give clinicians and other researchers an opportunity to look at vitamin D in a much larger context.”

The study builds on the knowledge of the ability of proteins to maintain their shape and function over time, or protein homeostasis. This biological function is one of the main items to fail with normal aging – often resulting in the accumulation of toxic insoluble protein aggregates implicated in a number of conditions, including Alzheimer’s, Parkinson’s and Huntington’s diseases, as well as type 2 diabetes and some forms of heart disease.

“Vitamin D3, which is converted into the active form of vitamin D, suppressed protein insolubility in the worm and prevented the toxicity caused by human beta-amyloid which is associated with Alzheimer’s disease,” said Lithgow. “Given that aging processes are thought to be similar between the worm and mammals, including humans, it makes sense that the action of vitamin D would be conserved across species as well.”

If he receives funding, senior author Lithgow plans to test vitamin D in mice to measure and determine how it affects aging, disease and function – and he hopes that clinical trials in humans will go after the same measurements. “Maybe if you’re deficient in vitamin D, you’re aging faster. Maybe that’s why you’re more susceptible to cancer or Alzheimer’s,” he said. “Given that we had responses to vitamin D in an organism that has no bone suggests that there are other key roles, not related to bone, that it plays in living organisms.”

“One theme continues to emerge from our work – that aging and disease stem from common mechanisms. Delaying disease by delaying the aging process is a serious proposition,” states Lithgow.