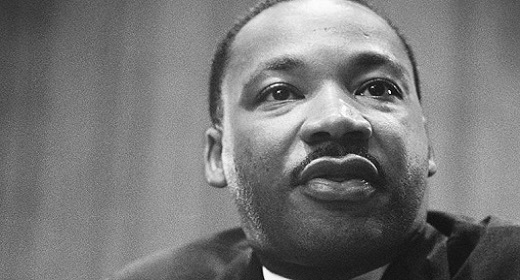

by Matthew Abrahams: As a philosopher and theologian, MLK’s vision was about more than just politics, says scholar and author Charles Johnson…

On Martin Luther King Jr. Day, Americans remember the civil rights icon whose words inspired a nation. “I have a dream that one day this nation will rise up and live out the true meaning of its creed: We hold these truths to be self-evident, that all men are created equal,” he said in his most celebrated speech, delivered from the Lincoln Memorial on August 28, 1963. While he dreamed of a future where people are not “judged by the color of their skin but by the content of their character,” Dr. King also had in mind a more just and loving world. A few lines later, he alludes to Isaiah 40:4: “I have a dream that one day every valley shall be exalted, every hill and mountain shall be made low, the rough places will be made plain, and the crooked places will be made straight, and the glory of the Lord shall be revealed, and all flesh shall see it together.”

For decades, scholar and award-winning author Charles Johnson has worked to bring attention to King’s spiritual and philosophical concerns, which often have been overshadowed by the impact of his nonviolent civil disobedience and political organizing. In 1998, some eight years after his novel Middle Passage won the National Book Award for Fiction, Johnson published Dreamer, a fictional account of the last two years of Martin Luther King’s life. (He was named a MacArthur fellow that same year.) Already having earned a doctorate in philosophy and a longtime student of Buddhism, Johnson recognized the rigor of King’s thinking and has sought—through Dreamer and other writings and talks—to restore this philosophical dimension of King’s work to his public image.

Here, Tricycle speaks with Johnson about his writings on Martin Luther King Jr. and what Buddhist practitioners, or any spiritual seeker, can learn from King’s message and vision.

At what point in your life did you realize that your interest in Dr. Martin Luther King Jr. might be more intense than the average person’s? How did that interest lead you to write a novel about the last two years of his life? Even though I grew up in the 1960s, and even though I remember the day Martin Luther King Jr. was assassinated, it wasn’t until the 1980s that I realized how little I knew about this man at the center of a civil rights movement that changed America, despite the fact that I invoked his name often. I felt the private man we call Martin Luther King Jr. had over time become a cultural object difficult to grasp in his individuality, in his humanness, and in the minutiae of his daily life, and this troubled me because those are the very foundations from which a public life arises. As a storyteller, the best way for me to correct these gaps in my knowledge was to make King the subject of my fourth novel, Dreamer, but I also co-authored with civil rights photographer Bob Adelman The Photobiography of Martin Luther King Jr., delivered many speeches across America on his eponymous holiday, and composed a short story and essays about his vision after seven years of research. By the time I was done, I’d devoted a fifth of my life to King’s memory and achievements, and I felt I could discuss his philosophy—he was a theologian and philosopher—as well as I can the positions of Plato, Aristotle, Aquinas, Descartes, Marx, or Heidegger.

You have noted many times throughout the years that most Americans have an incomplete picture of Dr. King. What do you think is the most detrimental misconception that people have about him? I feel any life in its totality is impossible to know. But what Malcolm X’s daughter once said of her father is also true for King: We selectively take pieces of him. So far too many Americans just see King as a civil rights leader for just black people. His vision was, of course, greater and more expansive than one with only political concerns.

In “Dr. King’s Refrigerator,” you wrote that Dr. King’s dissertation research “ranged freely over five thousand years of Eastern and Western philosophy.” The story goes on to portray him as having a revelation about what Buddhists would call interdependence. What was his relationship to the dharma? And how much of your own philosophy did you put into your depiction of him? The Buddhist experience is simply the human experience. What we Buddhists call interdependence, Pratitya-samutpada, or what Thich Nhat Hanh calls “interbeing,” is not an experience exclusive to the East. The dharma can be experienced anywhere. King is fully aware of our interbeing. In his sermon “The Three Dimensions of a Complete Life,” he reminds his audience that our lives are best seen as a We-relation, because “before you got here to church this morning, you were dependent on more than half the world. You get up in the morning and go to the bathroom, and you reach for a bar of soap, and that’s handed to you by a Frenchman. You reach over for a sponge, and that’s given to you by a Turk.” That vision does capture how I see things and leads to my feelings every day of thanksgiving, humility, and gratitude for the precious gift of life, which is immeasurably enriched by other lives from the moment we are born.

Dr. King may have had broad influences, but his faith was firmly placed in Jesus. How should Buddhists and other non-Christians approach his explicitly Christian sermons? What should they make of his instructions, say, to meditate on the life and teachings of Christ? How should Buddhists and non-Christians approach King’s Christian sermons? I’d say with an open mind. A mind free of prejudice and presuppositions. After one of my King talks decades ago, a philosophy teacher in the audience asked me a question during the Q&A. (I’d been forewarned about him by other professors.) He said, “Can we have King without the Christianity?” I gave him the obvious answer: No. You might have a well-meaning social or political activist of some kind, but my question is whether he or she lives by a moral code, one we can use to judge their actions. Will they kill, lie, or steal to realize their goals and desires? Will they have the fortitude of a King, whose faith in Jesus’s emphasis on love—his certainty that love could lead to a Beloved Community—sustained him through being stabbed in a Harlem bookstore, physically assaulted often, and forced to live with a $30,000 bounty on his head. To ask such a question would be like asking, can we have Buddhism without the four noble truths and the eightfold path? Meditating on the life and teachings of Jesus is, for me, as valuable for gaining insights as meditating on the lives of Shantideva, Bodhidharma, Francis of Assisi, Catherine of Genoa, or Martin de Porres.

What do you think has been the biggest change with regard to Dr. King’s dream in the more than two decades since Dreamer was published? During the last two decades (and longer), I’ve watched with growing sadness Americans insulting and tearing each other down. During the last four years of the Trump administration, our divisions of race, class, and gender, our divisiveness, and our Them vs. Us attitudes, have only increased, leading to the tragic assault on our nation’s Capitol on January 6, where five people died. I believe King would still argue for the importance of love in our social relations. But at this painful present moment he might feel love is asking for too much and instead insist that we must begin more simply with a basic respect for each other. We must start by speaking respectfully to each other, listening respectfully, and behaving as if the ephemeral life of every sentient being is as precious to us as our own.

America is a less religious country than it was during the life of Dr. King (though certain pockets may have become more dogmatic). What has happened to the role of faith in social action today? Do you expect, or hope, that role will change in the coming years? Rather than hold forth on faith, I’ll simply say that I believe in the importance of everyone having some form of spiritual practice. As a friend of mine once said, we human beings are not just “meat moving around.” We are consciousnesses. As the Buddha observed long ago, “All that we are is the result of what we have thought.” I would like to see more people achieve, through any spiritual practice of their choice, greater mastery over their minds, emotions, and their thoughts. No one is born with that ability. It must be cultivated daily if a person wants to create his (or her) life mindfully as an artist does a work in progress, shaping their character into the sort of person they want to be, engaging in our social relations with metta [lovingkindness] and, above all else, being of selfless service to others during our brief time on this earth. Is this “religion?” I would simply call it the love of wisdom, which is the literal meaning of the word philosophy.