by Francis Su: Mathematics and religion both embody awe-inspiring, eternal truths…

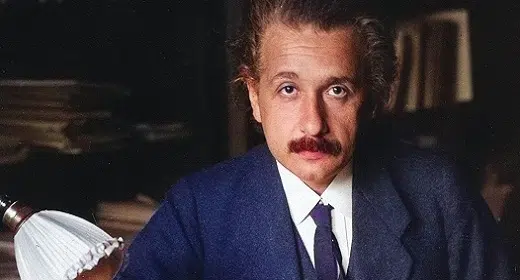

In a striking tribute to the mathematician Emmy Noether upon her death in 1935, Albert Einstein penned a New York Times appreciation lauding her discoveries, while at the same time drawing larger life lessons about the unselfish work of thinkers like her who illuminate human understanding. Mathematics, he says, is “the poetry of logical ideas.” Hinting at Noether’s success, he explains, “In this effort toward logical beauty, spiritual formulae are discovered necessary for the deeper penetration into the laws of nature.”

The word “spiritual” is a surprising adjective for “formulae,” isn’t it? “Elegant” might have been a more conventional word choice, and yet Einstein chose his words to underscore a more profound level of mathematical beauty.

Religious language is often employed by mathematicians, even among those who aren’t particularly pious. Paul Erdős, a famously prolific mathematician who was fond of referring to God as the Supreme Fascist, also liked to speak of “The Book” that God keeps in which all of the most beautiful proofs are recorded. He once quipped, “You don’t have to believe in God, but you should believe in the Book.” This unseen Book was an apparent nod to the timelessness of mathematical ideas, whose existence and persistence parallels the eternal nature that some expect of divine truths.

How math is like religion

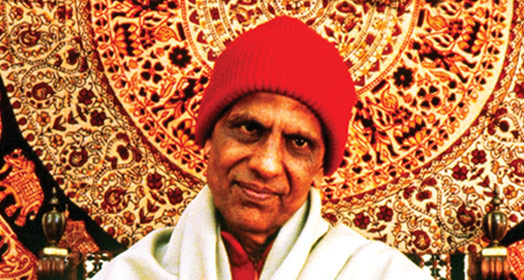

Mathematical pursuits and religious pursuits are alike in many ways and evoke similar feelings and responses in their devotees. However, this observation is not a universal claim about the faith convictions of mathematical thinkers. Throughout mathematical history, we find plenty of adherents of various faith traditions — Ramanujan, Agnesi, Euler, al-Khwārizmī, or even the Pythagoreans come to mind. However, many mathematicians are atheist or agnostic. A 1998 survey of National Academy members shows that mathematicians in that organization are less religious than the general public (though they are slightly more religious than other scientists). Even so, those who pursue mathematical experiences and those who pursue religious experiences share a lot in common.

Such commonality is in part due to the explanatory power of both mathematics and religion. Mathematics offers insights about physical phenomena. Religion offers insights about human nature. So it is natural to seek them out for wisdom in their respective domains. Their truths are not always directly apparent, sometimes taking years of study. And their interpretations or applications sometimes need to be challenged.

Both pursuits also reward struggle — a long obedience of following their respective precepts — with the reward of penetrating insights. Years of study in mathematics enable one to visualize the hidden structures of the world in ways that become second nature. Likewise, years of pious devotion enable a healthy moral vision so that one has no hesitation to do the right thing when that vision comes in conflict with one’s selfish nature. There is joy and reward in that growth.

Furthermore, both pursuits offer the possibility of surprise: “aha” moments of instant and awe-inspiring reorientation when solutions to hard problems suddenly become clear. For instance, a significant question in many religions is how one makes reparations for sinful deeds. The unexpected possibility of grace in the atonement for sin is a striking resolution not unlike an unexpected solution to a difficult mathematical problem. In each case, hallelujahs of delight — or relief — follow.

This rhythm of meditation punctuated by the possibility of joyous surprise means that both mathematical experiences and religious experiences can offer places of refuge and hope. During the COVID pandemic, sales of puzzles exploded. Why? Because during times of great distress, people seek diversion, and engaging in puzzles is an enjoyable form of mathematical thinking that isn’t just limited to mathematicians. The resolution of a puzzle brings joy, and the experience of wrestling with puzzles trains us to hope with each new puzzle that an answer will emerge. The pious can replace “puzzle” by “prayer” in the prior sentence without much change in sentiment. Thus, meditating on a puzzle or a prayer in hopeful anticipation of their resolutions — as a solace from worldly stresses — is not all that different.

Mathematics and the immortal

In both mathematics and in most religions, one comes face-to-face with the reality of immortal objects that we cannot see. Religious people are often mocked for belief and interaction with a non-physical supernatural God. And yet, such mockers have all learned to count, to interact and reason with non-physical Platonist conceptions of whole numbers, and even to apply them to what we call (by contrast) “the real world.” Mathematics puts us “in touch with immortality in the form of eternal mathematical laws” as the historian of mathematics D. E. Smith once noted. Additionally, many learned scientists have marveled at how this interaction can even take place. Einstein himself asked, “How can it be that mathematics, being after all a product of human thought which is independent of experience, is so admirably appropriate to the objects of reality?” In other words, it should surprise us that Platonic mathematical objects interact with the real world so constructively — but we take this marvel for granted.

In both mathematical and spiritual pursuits, one perceives truths of such transcendent depth that they evoke awe and veneration. The dignity of human beings, the corrupting nature of sin, the importance of justice, and the power of forgiveness are all truths that can be felt profoundly in a religious experience. Similarly, encounters with the beauty of symmetry or a deep connection between disparate ideas in mathematics can elicit profound astonishment in mathematical experiences. Sometimes these encounters are only glimpses, hints that something exists that is both greater and unseen.

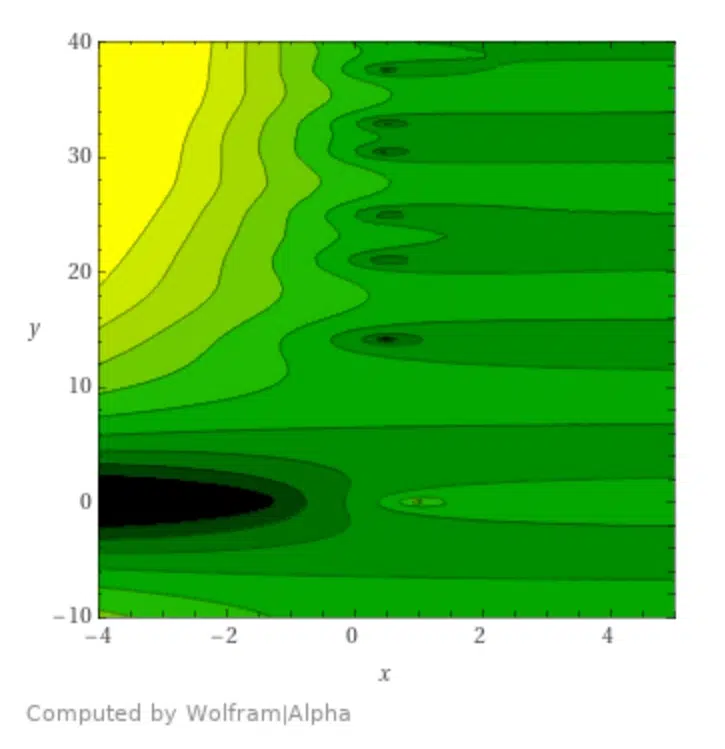

A mathematician who observes that the eigenvalues of random matrices show a striking similarity to the zeroes of the Riemann zeta function is led to ask: is that beautiful connection a coincidence, or is it a tantalizing clue to some deeper reality? Analogously, a faithful believer may see a divine hand in human events where others only see coincidence. And the faithful, when encountering the divine, feel compelled to worship. Einstein expressed a similar feeling: “If something is in me which can be called religious then it is the unbounded admiration for the structure of the world so far as our science can reveal it.” Scientists are no strangers to worship.

These commonalities of experience between mathematical pursuits and religious pursuits can offer a bridge of understanding, whether your interests lie in the numerous or in the numinous or in neither. Even if you have no emotional connection to a mathematical formula or a religious catechism — both of which can come across as tedious — you might begin to appreciate why others do. A formula has explanatory power. It represents a penetrating insight — the “aha” culmination of a struggle and a hope to understand something profound. It exemplifies the ability of human beings to interact with invisible, abstract truths that have an impact on our world. And if, as Einstein did, one sees the transcendent importance of Emmy Noether’s formulae to human progress and understanding the laws of nature, then indeed: perhaps it is appropriate to call such insights spiritual.