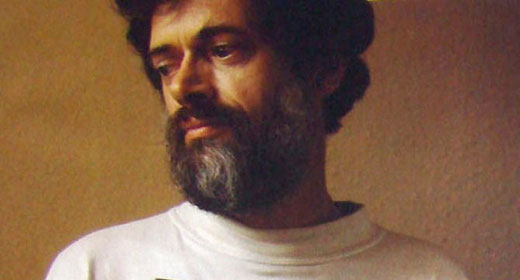

by Christopher Sirk: David Lynch is a true American culture icon, and a very unorthodox one at that.

His sensibility is comedic, philosophical, trippy, and scary in equal measure. He’s succeeded in transforming some of the most banal, cliched genre film conventions into an eminently weird, always envelope-pushing personal style. Lynch is a bonafide oddity—nobody can replicate him convincingly.

His sensibility is comedic, philosophical, trippy, and scary in equal measure. He’s succeeded in transforming some of the most banal, cliched genre film conventions into an eminently weird, always envelope-pushing personal style. Lynch is a bonafide oddity—nobody can replicate him convincingly.

But we may be able to replicate, to some degree, his philosophy of work, consciousness, and creativity. And he may just have some food for thought for all us normies.

From paperboy to icon: Lynch’s ‘straight story’

“What makes you worry about things… is when you start thinking about what certain people might say about it later. Because you’re not really sure what they might say. And if you start worrying, you could make some really strange decisions based upon that worry. The work isn’t talking to you anymore: the worry is talking to you. And you become paralyzed.”

—David Lynch. Chris Rodley, Lynch on Lynch.

Lynch credits much of his creative success to transcendental meditation (TM), which he started practicing in 1973.

At the time he began meditating he says he was filled with anxiety and fears, covered in what he refers to as “the suffocating rubber clown suit of negativity.” After a couple weeks of committed TM, the tragic clown was vanquished.

Post-clown suit of negativity, Lynch has become quite the TM evangelist. In 2005, he founded the David Lynch Foundation to promote the practice worldwide. He meditates 20 minutes per session, twice a day—a routine he’s maintained since the ’70s.

For him, meditation finally gave him the clarity to create. And create he did.

Lynch’s first film, released in 1977, was a little ditty by the name of Eraserhead. A black-and-white surrealist horror influenced by writers Kafka and Nikolai Gogol, it certainly didn’t scream out the word ‘spiritual’, but Lynch insists the nightmare fuel film is his most spiritual to date.

It took five long years to finish. Production was initially funded by the American Film Institute (AFI) where Lynch was studying in L.A., but their money quickly ran out. In order to keep the good ship Eraserhead afloat, some serious bootstrapping would be required.

So Lynch got himself a paper route, delivering the Wall Street Journal for $50 a week and funneling the salary, and any other small change, into the project. His industry friends Jack Fisk and Sissy Spacek floated him some cash too.

Production was on again, off again as money came in, got spent, and needed to be replenished. When the film was finally finished and released, it didn’t exactly scream ‘box office smash.’ However, in some oblique way, Eraserhead captured the post-Vietnam, pre-John Lennon assassination American zeitgeist. In the end, it made over $7 million in the USA as a midnight feature fixture and launched Lynch’s career.

For detractors, Lynch’s movies ‘make no sense’ and are emblematic of a troubled mind and desire for violence, voyeurism, and so on and so forth.

A good example is his 1986 film Blue Velvet, which at the time of its release received a lot of heat for its dark portrayal of human nature and sexuality (as you can see from this serious grilling during a contemporary TV interview). Film critic Roger Ebert also famously hated the movie, awarding it only 1 star.

In case you didn’t see it, the gist is: actor Isabella Rossellini, playing ‘woman in trouble’ Dorothy Vallens, is coerced into degrading (not to mention supremely odd) sex acts and forced to endure physical and emotional abuse from the ultimate ‘bad dad’— psychopathic figure Frank Booth, who is holding her husband and son hostage.

At the same time, she begins a masochistic relationship with the Hardy Boys-style teenage sleuth Jeffrey Beaumont (played by Kyle MacLachlan), who she catches breaking into her apartment and spying on her.

Not the most wholesome setup, but certainly a fascinating one.

And ultimately, if one spends some time with Lynch, it becomes clear that this film—like all his other ones before and since—was not made with the intention of shocking anyone (unlike other ‘dark’ filmmakers like Lars von Trier, Gaspar Noe, and any other self-professed art house sh*t disturbers).

Shock value was never what Lynch was after, rather the content of Blue Velvet is but one example of the natural result which occurs when Lynch explores ideas deep in his psyche, according to a very specific working process.

In all Lynch’s explanations of his creativity—from his book to interviews and lectures—we see the overriding concern he always has: Discovering a world that was hidden and allowing it to develop according to its own logic.

Transcendental Meditation and “Catching the Big Fish”

“Bliss is the sweetest nectar of life.”

—David Lynch

Lynch’s 2006 book, Catching the Big Fish: Meditation, Consciousness, and Creativity focuses on the practice of meditation as a means of diving in and catching the big idea.

He notes how, in life, there’s pressure and stress, anxieties and fears of some kind or another at all times. These factors may bring anger and a certain edge that can be useful in the creative process, but only when you have the ability to stand outside of your battles and observe them with clarity.

The key is to ‘transcend’ the immediate worries and negatives of your situation, to dive deep into a more pure and fundamental state of consciousness. When you do that, Lynch suggests, you enter into a form of happiness that goes beyond ‘goofy grins’ into something profound and durable.

In the process of ‘diving’, you expand your consciousness to be more awake, and with that, you have heightened awareness and access to more ideas: When you become a better swimmer, you can better catch the idea that you desire.

Even if you don’t catch ‘the big fish’, you’ll hopefully come out of the deep dive with a fragment, a clue that will eventually lead you towards putting together the final work.

Lynch likes to use the following analogy: In the other room, the puzzle is all put together, but you only have one, two, or a few pieces right now.

Diving into consciousness: The unified field

“Well, obviously, there’s got to be a way that these relate—because of this great unified field. There couldn’t be a fragment that doesn’t relate to everything. It’s all kind of one thing, I felt. So, I had high hopes that there would be a unity emerging, that I would see the way these things all related, one to another.”

—David Lynch. Catching the Big Fish.

Lynch leans on unified field theory from quantum physics to explain his TM approach to consciousness and creativity.

The underlying proposition of the theory is that, at the very bottom of all matter, there is some intermediary entity (which can be distilled into a single set of equations) uniting all the forces in the universe.

As a result, if we were able to link all known phenomena, we would gain a radically expanded understanding of nature, unlocking its hidden truths.

Albert Einstein is credited as the originator of this idea. In his work, he postulated that everything within the universe is relative, and thus all phenomena may only be understood in terms of relativity.

Einstein spent the last decades of his life trying to prove a physical theory for the interconnectedness of all things, but couldn’t quite put it all together.

The concept remains an open topic of exploration in the science word. Some scientists advocate a combining of general relativity and quantum mechanics theory to build a Theory of Everything™.

For practitioners of TM, the concept is often identified with an ‘upside-down’ view of consciousness. For them, as for Lynch, consciousness is ubiquitous in nature, meaning that the universe at large is conscious.

This is a (quite controversial) reversal of the dominant idea that consciousness is a superficial outcome of various electrochemical processes within the brain—a ‘fluke’ of the universe as a result of self-replicating molecules growing into complex organisms.

Dr. John Hagelin (who Lynch is a big fan of) suggests that unified field is a place where the laws of nature are “unified” into a compact field of all the intelligence, dynamism, and self-awareness of nature.

This zone supposedly holds nonlinear properties of self-interaction and self-referral, which “sequentially [bring] forth the diversified structure of creation.”

In other words, what he’s saying is that the localized physical reality of objects is too superficial. We have to consider the possibility that everything is somehow profoundly unified.

David Lynch, for one, treats the field as an ocean of consciousness, a place where you can grow your sense of self, not in any intellectual sense but rather in an experiential sense.

By deep-diving into the subtle and usually hidden levels of the mind, one can ‘bulk up’ their powers of self-awareness, self-knowledge, creativity, and all that other good stuff which is vital to doing good work.

Belief in a sublime brand of interconnectivity certainly goes some way towards explaining Lynch’s penchant for linking seemingly unlinkable things in his films, arriving at a narrative propelled by its own logic.

His 2006 film Inland Empire is maybe the best example of such mind-melting creativity.

Propelled by a hackneyed narrative about the Hollywood production of a ‘cursed’ film script, the film manages to link the story of a family of anthropomorphized rabbits, an ominous man by a tree with a red light bulb in his mouth, and a murder in Poland into a narrative that ‘makes sense’ as a constellation of related phenomena.

Indeed, the entire genesis of the film, according to Lynch, is down to him presenting actor Krzysztof Majchrzak (who plays Inland Empire’s nightmarish villain) with the choice of one key prop out of three: a rock, a piece of broken tile, or a red light bulb.

He chose the bulb… then stuck it in his mouth. Lynch’s brain lit up:

“I really had this feeling that if there’s a unified field, there must be a unity between a Christmas tree bulb and this man from Poland.”

We’ve all been there. You have a crazy Slavic man and an old light bulb from the cupboard—now what do you do?

The challenge is to find the third thing that unites these first two things. In the case of Inland Empire, linking these entities meant structuring the film around a series of ominously lit rooms, then having Majchrzak play a phantom who moves between them like a ghoul from a bad dream.

Even if you’re not Lynch, but rather some Joe or Joanna Blow working at a startup, you might still find this thought exercise useful to generate ideas from unlikely dialogues.

Keeping your eye on the donut

It’s a truism to note these days we’re bombarded by information all day, every day. And maybe that’s why we forget so often to check ourselves.

Even if our information consumption seems to be ‘making us better’, more informed, more cosmopolitan, more etc. etc….maybe gliding through New York Times op-eds throughout the workday, interspersed with NPR podcasts and YouTube related video rabbit holes is not that helpful for our psyches after all.

Lynch’s singular advice for creativity is to “keep your eye on the donut, not on the hole.”

All the other things that are going on in your life and the (generally negative-leaning) macro-events of the world at large shouldn’t matter when you’re trying to do your good work.

No Wikipedia articles about the Hapsburg family tree, no IKEA catalog browsing, no PBS Frontline. It’s all about staring at that oily crust of dough and pondering, concentrating, epiphanizing.

But is drifting into this ‘donut hole’ of distraction and junk content really so bad? For creative work, apparently, it is. Lynch insists in characteristically plain speak-yet-cryptic fashion that the hole “is so deep and so bad” while the donut is “a beautiful thing.”

Perhaps this explains why this teaser for Twin Peaks: The Return is more-or-less just a shot of Lynch eating a donut. Is it some kind of metaphor for him ‘finishing the project’ and exorcizing the creative process with the act of chewing and swallowing its externalized symbol? Or is it just a continuation of the series’ longstanding fixation on donut imagery, so helpfully illustrated by this one-minute supercut?

My guess—about a 50/50 split.

How to Lynch for work and growth

“It’s money in the bank. Meditate regularly. And then the second thing I do is drink coffee.”

—David Lynch

Perhaps all this talk of consciousness and unified field theory has caused crystal skull-shaped alarm bells to go off in your head. You can calm those fears, however. The basic ideas behind Lynch’s approach to finding peace of mind, doing innovative work, and unleashing creativity can be reduced to secular, basic everyday practices.

In order to become more enlightened, it’s no longer necessary to Yogic fly away from the planet and move to Maharishi Vedic City, Iowa to practice TM.

Meditation apps can help those of us who don’t have the luxury of taking time off for lengthy spiritual retreats, or can’t quite/don’t want to scratch together the $960 bucks or so it costs to learn TM with an accredited instructor.

A form of mantra-based meditation related to the TM that Lynch swears by is available through Headspace, for example. Mindfulness training, also available as an app, can help us, short-attention-spanned people, to concentrate our focus on simple, specific stimuli (which may or may not be a donut) and gain a better sense of perspective and purpose in our work.

While we may not all believe in the unified field theory, or a consciousness underneath all phenomena in the universe, the Lynchian exercise of thinking through linkages between two disparate concepts, and then seeking out a third unknown variable (or variables) that will make your work into a coherent whole, is a fresh idea.

It’s certainly applicable in everything from product iteration, programming, design, developing a creative concept for an advert or film—basically any process of thinking through ideas with the objective of putting something new in the world.

Meanwhile, many of us feel that we can only envy Lynch’s capacity for risk, his willingness to be vulnerable, and his tolerance for negative feedback. But it is always possible to develop and grow what vulnerability researcher Brené Brown dubs the ‘authentic self’, or what Lynch would call ‘your own voice.’

Indeed, it sounds a bit cornball, but as Lynch admonishes, above all else you really do have to believe in your work. That takes a form of courage we seek in other people but have a hard time coaxing out of ourselves.

In other words: teach yourself to fish, and you will eat…many fish. Thanks for the advice, David!