Claims of higher energy density, much faster recharging,

and better safety are why solid-state-battery technology appears to be the next big thing for EV batteries.

- Solid-state cells promise faster recharging, better safety, and higher energy density.

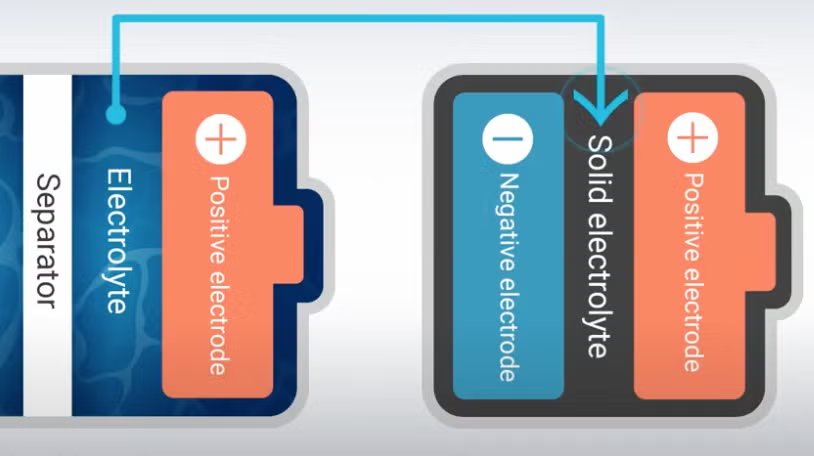

- They replace the liquid electrolyte in today’s lithium-ion cells with a solid separator.

- Honda, Toyota, and others hope to use solid-state cells in vehicles to go on sale before 2030.

Advances in battery technology—for consumer electronics and electric vehicles alike—are largely incremental, and have been since the advent of modern lithium-ion cells almost 30 years ago. Three factors combine to reduce costs at roughly 8 percent a year: tweaks to battery chemistries, higher yields at cell factories, and economies of scale from high-volume production.

Longtime Holy Grail

The next big battery advance may be solid-state cells, long a Holy Grail for battery engineers all over the world. They offer the lure of greater energy density, faster recharging, and better safety than cells with liquid electrolytes. Some do away entirely with today’s graphite anodes—a substance whose processing and supply is controlled entirely by Chinese producers.

How large are the gains? According to what Toyota has announced about its future battery plans, a pack employing a solid-state battery could improve the range by nearly 70 percent and reduce 10 to 80 percent DC fast-charging time from 30 minutes to 10. Although any range claims are affected substantially by the assumptions of the underlying vehicle and characteristics such as weight and aerodynamics.

Developing solid-state cells has led dozens of companies globally to spend tens of billions of dollars on R&D over the past decade and a half. Now, the goal may be getting closer. Multiple carmakers across the globe have announced pilots, prototypes, or other advances in solid-state cells. Expect that pace to ramp up over the next few years.

The Many Types of “Solid State”

With “solid state” as the battery buzzword du jour, it’s useful to understand how a solid-state cell differs from today’s cells with liquid electrolytes. The problem is compounded because “there is no broad agreement on the definition of ‘solid state,'” notes Haresh Kamath, who designed battery cells for spacecraft at Lockheed Martin. (He is presently the director of distributed energy resources and energy storage at the Electric Power Research Institute, or EPRI, an independent, nonprofit research organization for the U.S. electric utility industry.)

In other words, take any mention of solid-state cells for EVs, whether from a carmaker or a battery company, with a grain of salt until you dive into the particulars.

Broadly speaking, the term “solid state” refers to using a solid material for both the separator that keeps anode and cathode from touching and the medium through which the electrons pass as the cell discharges or charges. The liquid electrolyte in today’s cells, a flammable organic solvent, is absorbed by the three materials (anode, cathode, and separator), all somewhat spongy. Unlike a lead-acid starter battery, the cell has no excess liquid sloshing around, only enough to moisten the electrodes.

Losing the Liquid Electrolyte

Several variations of separator and medium exist between today’s liquid electrolytes and tomorrow’s full solid-state cells:

- Semi-solid electrolytes in quasi-solid-state cells, of which so-called lithium-polymer batteries (using liquid electrolyte held in a polymerized gel) may be the best-known.

- High-temperature, non-liquid, ionically conductive polymers (extensively tested a decade ago).

- Ceramic-coated polymers, also requiring high operating temperatures.

- Pure ceramics (oxides, sulfides, phosphates) or glass solid electrolytes, also requiring high temperatures.

The last three allow the use of lithium metal anodes, with a cathode of either lithiated metal oxide (nickel oxide, aluminum oxide, manganese oxide, cobalt oxide, or some blend of those), or iron phosphate.

Alternatively, using lithium metal as a cathode with a solid-state separator can also allow what are called “anode-free cells”: those in which the anode is supplanted by a copper current collector on which lithium metal is deposited during charge. This obviates the need for graphite—a substance for which China presently controls the bulk of global production.

But lithium metal has its own safety risks. Solid lithium metal is highly flammable at any temperature, reacting violently with moisture, water, or steam. Any cell maker using solid lithium will be under intense scrutiny to prove its new cells are at least as safe as today’s, let alone supporting claims of much greater safety.

Accelerating Pace of News

Recent solid-state news includes a November announcement by Honda that it would set up a test production line for solid-state cells to understand which materials and processes would offer cost-competitive high volumes for the new technology.

In October, Stellantis said its partner Factorial would test its “semi-solid state” cellsunder real-world test conditions in a fleet of electric Dodge Charger Daytonas—although not until 2026. Those cells feature a “quasi-solid electrolyte” with a lithium anode (rather than graphite).

Chinese maker Chery claimed to China Car News that it is in the process of creating the world’s first all-solid-state battery production line with production capacity of more than 1 Gigawatt-hour (enough for 100,000 EVs with 100-kilowatt-hour battery packs) in Wuhu, Anhui Province. It also laid out plans for its next two generations of solid-state cell technology. It is doing so as part of Anhui Anwa New Energy Technology, a joint venture founded in 2020 with Chinese battery maker Gotion and various Japanese and Thai partners.

Trial and Error Humbles the Mighty

Still, like any advance at the cutting-edge of electrical or electronic technology, solid-state cells are really, really hard to take from the lab to production EVs. For every 100 promising lab tests of batteries in general, perhaps one will advance to a prototype line—and fewer yet into high-volume production. Toyota learned that lesson 15 years ago, when it couldn’t produce the lithium-ion cell it chose for the third-generation 2010 Toyota Prius—and had to revert to its tried-and-true, 15-year-old nickel-metal hydride cells.

Toyota has long been a proponent of solid-state cells. It has said it believes EVs will not be suitable for mass adoption until solid-state batteries arrive. But even mighty Toyota has struggled to get solid-state cells into production. It first showed a prototype solid-state cell 15 years ago, in December 2010. Through most of the 2010s, it said it would put solid-state cells into production by 2020. In late 2023, the company announced that date had slipped to 2027.

Once new cells go into production, there’s a whole validation process before carmakers can commit to using them in production vehicles. Solid-state cells are likely to enter the market at a higher price than conventional lithium-ion cells; making them cost-competitive with today’s cells will be key. Honda claims its solid-state cells will be made using methods similar to the standard production process for liquid-electrolyte lithium-ion cells.

Cells and Cars: Before the End of the 2020s?

Siva Sivaram, CEO of pure solid-state cell startup QuantumScape, told Reuters in December that he expects, “In 2025, at least two companies will announce that they have a solid-state battery. And by the end of 2025, somebody will announce that that hey, they are planning on a car with solid state batteries . . . [though] they won’t tell you when.”

And, he added cautiously, “Solid-state batteries are going to be in high volume [production] in the late part of this decade.”

Will the Chinese play a role? “I don’t think [pure solid-state cells] will come from China,” he said. (Chinese cell makers and EV companies undoubtedly differ.) Eliminating graphite anodes entirely, Sivaram noted, counters one of China’s strengths in EV batteries. It would free battery makers from needing a material for which China presently controls the supply chain.

So the pace of announcements now suggests solid-state cells will indeed come to EVs to be sold in North America, perhaps before 2030. But we wouldn’t bet on any particular year in which that’ll happen—at least, not yet.

The author of this story has summarized electric-vehicle news for the Electric Power Research Institute (EPRI).