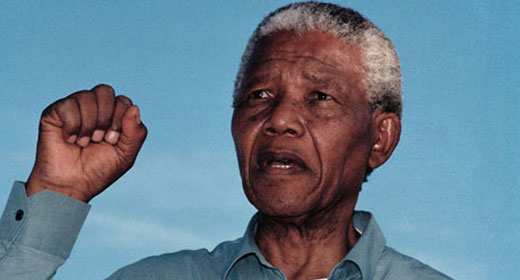

John Carlin knew Mandela in the tumultuous years just after his release. Here he tells of the private meetings that proved he was a master at winning over even the most implacable opponents.

Nelson Mandela arrived early for work on 11 May 1994, the day after his inauguration as the first black president of South Africa. As he walked down the deserted corridors, past framed watercolours celebrating the derring-do of white settlers at the time of the Great Trek, he paused outside a door and knocked.

A voice said “Come in” and Mandela, who was 6ft, found himself looking up at a vast, second-row forward of a man, an Afrikaner by the name of John Reinders, chief of presidential protocol during the tenure both of the last white president, FW de Klerk, and his predecessor, PW Botha.

“Good morning, how are you?” said Mandela, with a cheery grin.

“Very well, Mr President, and you?”

“Very well, ve-ry well …” Mandela replied. “But, ah … may I ask, what are you doing?”

Reinders, who was packing away his belongings into cardboard boxes, replied: “I am taking away my things, Mr President. I am moving to another job.”

“Ah, very good. Where is it you are going?”

“Back to the prisons department. I served there as a major before coming to work here in the presidency.”

“Ah, no,” Mandela grinned. “No, no, no. I know that department ve-ry well. I would not recommend doing that.”

Turning serious, Mandela proceeded to persuade Reinders to stay. “You see, we people, we are from the bush. We do not know how to administer a body as complex as the presidency of South Africa. We need the help of experienced people such as yourself. I would ask you, please, to stay at your post. I intend only to serve for one presidential term and then, of course, you would be free to do as you wish.”

Reinders, as astonished as he was charmed, needed no further explanations. Slowly, shaking his head in wonder, he began to empty his boxes.

Reinders, whose eyes filled with tears as he recalled that story some time later, told me that during the five years he had served at Mandela’s side, travelling far and wide with him, he had received nothing but courtesy and kindness. Mandela treated him with the same respect, he said, as he showed the president of the United States, the pope or Britain’s Queen, who, incidentally, adored him. Mandela must have been the only person in the world, with the possible exception of the Duke of Edinburgh, who always called her “Elizabeth” – or at least who was able to do so without drawing even a shadow of a rebuke. (A friend of mine who was having dinner with him once at his home in Johannesburg recalled how a servant came in with a portable phone. It was the Queen on the line. Smiling broadly, Mandela put the phone to his ear and exclaimed: “Ah, Elizabeth! How are you? How are the children?”)

What Mandela’s relationship with Reinders – the same as it was with all his staff, however humble their position – reveals is the secret of his success as a political leader.

If politics is about winning people over, Mandela, as numerous other politicians have attested, was the master of the game. He had at his command an irresistibly seductive cocktail that combined boundless charm born of a vast self-confidence with inflexible principle, strategic vision and the canniest pragmatism.

The attitude he adopted towards Reinders was the same one he displayed to his interlocutors in the apartheid government when he first met them in secret talks during the last five years of the 27-and-a-half he spent in prison; it was the one he showed the white population as a whole in eventually convincing practically the totality of them that, far from being a fearful terrorist, as they had been programmed to believe during his captivity, he was as much their rightful president as he was black South Africa’s uncrowned king.

It would have been much harder for him to prevail on white South Africa to abandon apartheid and relinquish power before he went to prison, in 1962, and harder still 20 years earlier, when he signed up for the black freedom struggle.

The man responsible for recruiting him was Walter Sisulu, a shrewd labour activist who at the time of that fateful meeting (Mandela would later joke that he would have spared himself a great deal of trouble had he never met Sisulu) was a labour activist with more than 10 years behind him in the movement that would eventually spearhead black South Africa’s liberation, the African National Congress (ANC).

Back then, Mandela was a young man on the make, freshly arrived in Johannesburg from rural Transkei, where he had been born and raised in what passed, amid the general squalor of his surroundings, for tribal privilege. That he had also received a solid secondary education did not disguise the fact that, standing there in the labour activist’s office, he was the country bumpkin to Sisulu the city slicker. Yet it was Sisulu, 30 years old to Mandela’s 24, who was impressed, glimpsing in Mandela the seed of a talent for politics that would take many years of struggle and sacrifice to mature.

Recalling five decades later how he had sized up the young man standing tall before him in his office, Sisulu said: “He happened to strike me more than any person I had met. His demeanour, his warmth … I was looking for people of calibre to fill positions of leadership and he was a godsend to me.”

It took little time for Sisulu to convince Mandela, then working towards a degree in law, to join his cause. Mandela succeeded on both counts, going on to set up a law firm with another ANC leader, Oliver Tambo. But he was especially successful in politics.

To the charisma Sisulu had spotted in him Mandela added an impetuous courage that during the 1940s and 1950s, before he went to prison, derived partly from his indignant sense of the injustice black South Africans were obliged to endure, but also from the boisterousness of his character.

He quickly rose to become president of the ANC Youth League, from which position he led a nationwide defiance campaign against a regime whose apartheid laws constitutionally entrenched the humiliation and condition of de facto slavery to which black people on the southern tip of Africa had been reduced since the arrival of the first white settlers in 1652.

It was during this campaign that Mandela revealed a histrionic talent (his official biographer, Anthony Sampson, described him as “a master of political imagery”) that would serve him in good stead much later, when he emerged from prison into the globalised television age. He made a point of ensuring that press photographers were amply in attendance when he launched the campaign in 1952 by setting fire to his pass book, badge of apartheid ignominy, wearing a big mischievous smile on his face. The photograph, published far and wide, electrified the black population, who followed his example in their tens of thousands.

The young Mandela’s self-confidence bordered on the brash. At a meeting of the ANC’s executive committee in the mid-1950s he upset the organisation’s elders when he gave a speech in which he predicted – with outrageous clairvoyance – that one day he would become the first black president of South Africa.

Always visibly on the frontline of resistance to apartheid in those days, he dressed like a million dollars. He had his suits made by the same tailor as South Africa’s gold and diamond king, Harry Oppenheimer, and never cut a less than dandyish figure on the Johannesburg night scene.

Photographs of the 1950s show a man with the confident air of a Hollywood matinée idol. The women fell for him, Winnie Madikizela among them. And he – though he was married, with children – fell for her too. She was Soweto’s Ava Gardner to his Clark Gable. Mandela divorced his first wife, Evelyn, and wed Winnie, with whom he had two daughters but, as Winnie would later complain, they saw little of each other, especially after he became commander in chief of the ANC’s newly founded military wing, Umkhonto we Sizwe, Spear of the Nation, in 1961, and was obliged to go underground.

That seam of vanity worked against him now. Determined to play the part of Che Guevara, embracing a slogan popular at the time – “We’ll take power the Castro way” – he insisted, despite warnings from his friends, on sporting revolutionary green fatigues in public even after the police had declared him South Africa’s most wanted man. Partly because of his failure to keep the very low profile his circumstances demanded, he was arrested in 1962, remaining behind bars for the next 27-and-a-half years.

Prison tamed him, taught him to hone his theatrical talents, his seducer’s arts, towards realistic political goals. He went in angry and came out wise, yet always driven by the heroic conviction that the respite he won at his trial in 1964 – life imprisonment instead of an expected death sentence – had destined him to emerge one day as his people’s redeemer.

The big lesson he assimilated was that the enemy was not going to be defeated by force of arms; that white South Africans would one day have to be persuaded to surrender power voluntarily, to kill off apartheid by themselves.

Prison, the tiny cell he inhabited on Robben Island for 18 years, became his practice ground for the grand game that would await him outside. Lesson one, he resolved, had to be “know your enemy”. To the dismay of some of his fellow prisoners, he set about learning Afrikaans – “the oppressors’ language” – and reading books on Afrikaner history. Then he set out to win his jailers’ hearts, figuring this was the way to get to know the vanities, strengths and weaknesses of the white population at large, the better to be prepared, when the time came, to attempt to bend them to his will.

The trick consisted of never losing his principled dignity, in refusing to be bullied and in treating all around him with respect – with the “ordinary respect” that Sisulu once defined as the prize for which he fought during his 60 years in politics. These qualities, adorned by his regal manners, were to win over the first two members of the white government that he, or any other black leader, ever had contact with.

During his last five years in prison he held more than 70 secret meetings with the justice minister, Kobie Coetsee, and national intelligence chief, Niel Barnard; the meetings’ purpose to explore the possibility of a political accommodation between blacks and whites. As he insinuated himself into these two dubious personages’ trust (each was regarded as a monster by the world at large during the fraught 1980s), he consolidated his authority over his fellow political prisoners, as he would later over the black population.

I interviewed Coetsee about those meetings and, as Reinders had done, he wept at the recollection of Mandela, whom he defined as “the incarnation of the great Roman virtues – dignitas, gravitas, honestas”. Barnard was incapable of weeping but he came close, referring to Mandela always during the seven hours that we spoke as “the old man”, as if he were talking about his own father.

Released from prison on 11 February 1990, Mandela went on a triumphant progress around South Africa, preaching a finely tuned message of reconciliation and defiance. No Gandhi, he refused to call off the “armed struggle”, symbolic as it had largely been, until the government gave unequivocal signs of committing itself to one-person, one-vote democracy.

He had no choice, for President FW de Klerk, whom he graciously (and shrewdly) described as “a man of integrity”, initially imagined he would get away with some sort of sui generis, semi-democratic, “minority rights” formula that would secure and perpetuate white privilege. The negotiations that went on over the next four years were tough, but not nearly as tough as what was going on out in the townships, especially those on the periphery of Johannesburg.

The last kicks of the apartheid beast expressed themselves in a concerted attempt to derail the transition by shadowy forces in the security establishment in alliance with the conservative black organisation Inkatha, whose rightwing Zulu leader, Mangosuthu Buthelezi, a beneficiary of apartheid’s Bantustan “homeland” system, was as fearful of ANC rule as any white man. The slaughter in Soweto and elsewhere reached a scale not seen in South Africa since the Boer war, nearly 100 years earlier.

Mandela railed publicly, raged at De Klerk in private and had to be restrained by colleagues in the ANC national executive from not calling off talks altogether; from resorting – hot anger at times getting the better of his judgment – to all-out confrontation. Yet when the supreme test came he kept his cool and gave his blessing to a breakthrough compromise whereby the country’s first democratically elected government would be a coalition, with ministries dispensed in proportion to the percentage of votes each party won.

He reached out to, and to a large degree pacified, the white population by persuading his own people to make another major compromise on a matter close to all South African hearts.

It was at a meeting of the ANC’s national executive four months before the historic elections of April 1994. There was never any doubt that the ANC would win the poll; the issue on the table was what should be the position of the new government on the delicate question of the national anthem? The old anthem was clearly unacceptable. Die Stem was a sombre martial tune that praised God and celebrated the triumphs of Boer leaders Piet Retief, Andries Pretorius and the rest of the “trekkers” as they drove upwards through South Africa in the 19th century, crushing black resistance. The unofficial anthem of black South Africa, Nkosi Sikelel’ iAfrika, was the richly soulful expression of a long-suffering people yearning to be free.

The meeting had just got started when an assistant walked in to tell Mandela that he had a phone call from a head of state. He left the room and the 30 or so men and women of the ANC’s supreme decision-making body carried on without him. The consensus was overwhelmingly in favour of scrapping Die Stem and replacing it with Nkosi Sikelel’ iAfrika. Tokyo Sexwale, the former Robben islander and now leading member of the ANC’s national executive committee (NEC), remembered vividly the mood at the meeting during Mandela’s absence.

“We were enjoying ourselves,” he said. “It is the end for that Die Stem song, we said. The end. No more. We are singing Nkosi Sikelel’ iAfrika in this country and that is that. We were having a great time!” Then Mandela walked in. “We were all like small primary schoolchildren,” recalled Sexwale, a big powerful man, with a rich orator’s voice. “He asked us how our discussions were going and we told him we had already reached a decision. He said, ‘Well, I am sorry. I don’t want to be rude, but …’ – my God, we all wanted to hide – ‘I think I should express myself on this motion. I never thought seasoned people such as yourselves would take a decision of such magnitude on such an important matter without even waiting for the president of your organisation’.”

And then Mandela, as sternly schoolmasterish as his fellow ANC leaders had ever seen him, put across his point of view. “This song that you treat so easily holds the emotions of many people who you don’t represent yet. With the stroke of a pen, you would take a decision to destroy the very – the only – basis that we are building upon: reconciliation.”

The men and women of the national executive of the ANC, many of them household names in South Africa, regarded as heroes and heroines of the struggle, cringed with embarrassment. Mandela proposed instead that, for the foreseeable future, South Africa should have two anthems, to be played one immediately after the other at official ceremonies, from presidential inaugurations to international rugby matches: Die Stem and Nkosi Sikelel’ iAfrika.

Morally defeated, overwhelmed by the logic of Mandela’s argument, the freedom fighters unanimously caved in. Sexwale laughed out aloud years later at the discomfiture he had felt, at the manner in which Mandela had outmanoeuvred them all. “Jacob Zuma, who had been chairing the meeting said, ‘Well, I … I … I think the matter is clear, comrades. I think the matter is clear …’ Nobody raised a finger to object.”

The national executive capitulated in the face of Mandela’s wrath because they understood immediately that their vindictiveness on the white anthem had been childish, that the far-sighted political response to the dilemma was the mature generous one Mandela advocated. But they deferred to his judgment also because ever since the masterly performances he delivered immediately after leaving prison they had come to accept that “the old man” was far more skilful than any of them in the modern craft of political symbolism.

The issue of the anthem was all about the creation of a national mood, of persuading politically by moving people’s emotions. That, as his fellow ANC leaders had come to see, was the essence of his political genius, where he outclassed them all. He himself told me during one of our conversations in his home that he had lectured the NEC on winning over the Afrikaners, on showing respect for their symbols, on going out of your way to employ a few words of Afrikaans at the beginning of a speech. “You don’t address their brains,” he said. “You address their hearts.”

He did the same, with even more spectacular success, one year into his presidency at the rugby World Cup, staged in South Africa for the first time. Here he managed the unlikely feat of persuading his own people to back the South African Springboks, transforming one of the most hated symbols of apartheid oppression into an instrument of unity. Despite the fact that only one of the players in the national team was not white, the black population, at Mandela’s bidding, accepted the Springboks as their own, as fitting representatives of the new national flag. Unforgettably, at the final in Johannesburg, which South Africa won, the almost entirely white crowd (the rugby set had hardly been in the vanguard of racial enlightenment during the apartheid years) rose to bellow out his name, “Nelson! Nelson! Nelson!” When Mandela handed over the cup to the captain Francois Pienaar, a big blond son of apartheid, he said to him: “Thank you, Francois, for what you have done for our country.” “No, Mr President,” replied Pienaar, with enormous presence of mind. “Thank you for what you have done for our country!”

On that day, probably the happiest – and certainly the most patriotically united – in South African history, Mandela achieved his twin mission impossible of political leadership. He persuaded a whole people, in this case the most racially divided people on Earth, to change their minds.

Mandela’s chief purpose during his five years as president was to cement the foundations of the new democrac and banish the prospect of a terrorist counter-revolution by the heavily armed far right. This he managed. South Africa, for all the problems it faces today (problems which it shares with dozens of other countries, having shed the epic and awful singularity that once set it apart from the rest of the world), is a stable democracy, far more observant of the rule of law and freedom of speech than, say, Russia, another country that put paid to years of tyranny at more or less the same time.

It has been said, and will be for a long time probably, that he might have done more to redress the economic injustices of apartheid. Perhaps, but in a country with a high birthrate and no economic growth figures to match, it was a practically impossible challenge. The best that could be said was that Mandela’s presidency saw the emergence of a potent new social phenomenon, unimaginable in the apartheid years – a flourishing black middle class. He could have set about a wholesale redistribution of the nation’s wealth, but that would almost certainly have provoked what he most feared, a racial civil war. The economy left from that would have been an economy of the graveyard. It was democracy that Mandela fought for during the better part of his life and, once that was achieved, his priority became peace.

The sort of peace he brokered with John Reinders, whose treatment by Mandela shines a light on the great lesson he teaches all people everywhere, whether in political leadership or in less ambitious spheres of life. He was utterly consistent in what he practised and what he preached. He spoke of justice and of respect and he treated all people, however lowly their condition or however irrelevant to his political or personal objectives, with equal consideration.

A year after Mandela had left the presidency, Reinders, who continued serving his successor Thabo Mbeki, received a phone call from his former boss. Would he and his family be available to come to lunch at Mandela’s home the following Sunday? Reinders turned up with his wife and two sons expecting to be part of a large gathering. But it was only his family that Mandela expected.

At the beginning of the lunch Mandela raised a glass and, addressing himself to Reinders’s wife and children, apologised for having deprived them for so long of the company of their husband and father: “But he was magnificent in the performance of his duties. Magnificent!” Reinders, who once again wept recalling the story, said that after lunch Mandela accompanied them outside and, as their car left, stood and waved them goodbye.

I once asked Archbishop Desmond Tutu, a Nobel peace prize winner like Mandela, and one of the people who knew him most intimately, if he could define Mandela’s greatest quality. Tutu thought for a moment and then – triumphantly – uttered one word: magnanimity. “Yes,” he repeated, more solemnly the second time, almost in a whisper. “Magnanimity!”

There is no better word to define Mandela. No leader more big-hearted, more regal, more generously wise. Not now and, quite possibly, not ever.