In his use of critical reasoning, by his unwavering commitment to truth, and through the vivid example of his own life, fifth-century Athenian Socrates set the standard for all subsequent Western philosophy.

Since he left no literary legacy of his own, we are dependent upon contemporary writers like Aristophanes and Xenophon for our information about his life and work. As a pupil of Archelaus during his youth, Socrates showed a great deal of interest in the scientific theories of Anaxagoras, but he later abandoned inquiries into the physical world for a dedicated investigation of the development of moral character. Having served with some distinction as a soldier at Delium and Amphipolis during the Peloponnesian War, Socrates dabbled in the political turmoil that consumed Athens after the War, then retired from active life to work as a stonemason and to raise his children with his wife, Xanthippe.

After inheriting a modest fortune from his father, the sculptor Sophroniscus, Socrates used his marginal financial independence as an opportunity to give full-time attention to inventing the practice of philosophical dialogue.

For the rest of his life, Socrates devoted himself to free-wheeling discussion with the aristocratic young citizens of Athens, insistently questioning their unwarranted confidence in the truth of popular opinions, even though he often offered them no clear alternative teaching.

Unlike the professional Sophists of the time, Socrates pointedly declined to accept payment for his work with students, but despite (or, perhaps, because) of this lofty disdain for material success, many of them were fanatically loyal to him. Their parents, however, were often displeased with his influence on their offspring, and his earlier association with opponents of the democratic regime had already made him a controversial political figure. Although the amnesty of 405 forestalled direct prosecution for his political activities, an Athenian jury found other charges—corrupting the youth and interfering with the religion of the city—upon which to convict Socrates, and they sentenced him to death in 399 B.C.E. Accepting this outcome with remarkable grace, Socrates drank hemlock and died in the company of his friends and disciples.

The growing power of Athens had frightened other Greek states for years before the Peloponnesian War broke out in 431. During the war, Pericles died in the plague of Athens (429); fortunes of war varied until a truce was made in 421, but this was never very stable and in 415 Athens was persuaded by Alcibiades, a pupil of the Athenian teacher, Socrates, to send a huge force to Sicily in an attempt to take over some of the cities there. This expedition was destroyed in 413.

Nevertheless Athens continued the war. In 411 an oligarchy (“rule by a few”) was instituted in Athens in an attempt to secure financial support from Persia, but this did not work out and the democracy was soon restored. In 405 the last Athenian fleet was destroyed in the battle of Aegospotami by a Spartan commander, and the city was besieged and forced to surrender in 404. Sparta set up an oligarchy of Athenian nobles (among them Critias, a former associate of Socrates and a relative of Plato), which because of its brutality became known as the Thirty Tyrants. By 403 democracy was once again restored. Socrates was brought to trial and executed in 399 Socrates (469-399), despite his foundational place in the history of ideas, actually wrote nothing. Most of our knowledge of him comes from the works of Plato (427-347), and since Plato had other concerns in mind than simple historical accuracy it is usually impossible to determine how much of his thinking actually derives from Socrates.

The most accurate of Plato’s writings on Socrates is probably the The Apology. It is Plato’s account of Socrates’s defence at his trial in 399 BC (the word “apology” comes from the Greek word for “defence-speech” and does not mean what we would think of as an apology). It is clear, however, that Plato dressed up Socrates’s speech to turn it into a justification for Socrates’s life and his death. In it, Plato outlines some of Socrates’s most famous philosophical ideas: the necessity of doing what one thinks is right even in the face of universal opposition, and the need to pursue knowledge even when opposed Socrates wrote nothing because he felt that knowledge was a living, interactive thing. Socrates’ method of philosophical inquiry consisted in questioning people on the positions they asserted and working them through questions into a contradiction, thus proving to them that their original assertion was wrong. Socrates himself never takes a position; in The Apology he radically and sceptically claims to know nothing at all except that he knows nothing. Socrates and Plato refer to this method of questioning as elenchus , which means something like “cross-examination” The Socratic elenchus eventually gave rise to dialectic, the idea that truth needs to be pursued by modifying one’s position through questioning and conflict with opposing ideas. It is this idea of the truth being pursued, rather than discovered, that characterizes Socratic thought and much of our world view today. The Western notion of dialectic is somewhat Socratic in nature in that it is conceived of as an ongoing process. Although Socrates in The Apology claims to have discovered no other truth than that he knows no truth, the Socrates of Plato’s other earlier dialogues is of the opinion that truth is somehow attainable through this process of elenchus .

The Athenians, with the exception of Plato, thought of Socrates as a Sophist, a designation he seems to have bitterly resented. He was, however, very similar in thought to the Sophists. Like the Sophists, he was unconcerned with physical or metaphysical questions; the issue of primary importance was ethics, living a good life. He appeared to be a sophist because he seems to tear down every ethical position he’s confronted with; he never offers alternatives after he’s torn down other people’s ideas.

He doesn’t seem to be a radical sceptic, though. Scholars generally believe that the Socratic paradox is actually Socratic rather than an invention of Plato. The one positive statement that Socrates seems to have made is a definition of virtue (areté): “virtue is knowledge.” If one knows the good, one will always do the good. It follows, then, that anyone who does anything wrong doesn’t really know what the good is. This, for Socrates, justifies tearing down people’s moral positions, for if they have the wrong ideas about virtue, morality, love, or any other ethical idea, they can’t be trusted to do the right thing

Our best sources of information about Socrates’s philosophical views are the early dialogues of his student Plato, who attempted there to provide a faithful picture of the methods and teachings of the master. (Although Socrates also appears as a character in the later dialogues of Plato, these writings more often express philosophical positions Plato himself developed long after Socrates’s death.) In the Socratic dialogues, his extended conversations with students, statesmen, and friends invariably aim at understanding and achieving virtue {Gk. areth [aretê]} through the careful application of a dialectical method that employs critical inquiry to undermine the plausibility of widely-held doctrines. Destroying the illusion that we already comprehend the world perfectly and honestly accepting the fact of our own ignorance, Socrates believed, are vital steps toward our acquisition of genuine knowledge, by discovering universal definitions of the key concepts governing human life.

Interacting with an arrogantly confident young man in Euqufrwn (Euthyphro), for example, Socrates systematically refutes the superficial notion of piety (moral rectitude) as doing whatever is pleasing to the gods. Efforts to define morality by reference to any external authority, he argued, inevitably founder in a significant logical dilemma about the origin of the good. Plato’s Apologhma (Apology) is an account of Socrates’s (unsuccessful) speech in his own defense before the Athenian jury; it includes a detailed description of the motives and goals of philosophical activity as he practiced it, together with a passionate declaration of its value for life. The Kritwn (Crito) reports that during Socrates’s imprisonment he responded to friendly efforts to secure his escape by seriously debating whether or not it would be right for him to do so. He concludes to the contrary that an individual citizen—even when the victim of unjust treatment—can never be justified in refusing to obey the laws of the state.

The Socrates of the Menwn (Meno) tries to determine whether or not virtue can be taught, and this naturally leads to a careful investigation of the nature of virtue itself. Although his direct answer is that virtue is unteachable, Socrates does propose the doctrine of recollection to explain why we nevertheless are in possession of significant knowledge about such matters. Most remarkably, Socrates argues here that knowledge and virtue are so closely related that no human agent ever knowingly does evil: we all invariably do what we believe to be best. Improper conduct, then, can only be a product of our ignorance rather than a symptom of weakness of the will {Gk. akrasia [akrásia]}. The same view is also defended in the PrwtagoraV (Protagoras), along with the belief that all of the virtues must be cultivated together.

Socrates

Socrates (June 4, 470 – 399 BC) (Greek Sokrátes) was a Greek (Athenian) philosopher and one of the most important icons of the Western philosophical tradition.

Socratic method

His most important contribution to Western thought is his dialogical method of enquiry, known as the Socratic method or method of elenchos, which he largely applied to the examination of key moral concepts and was first described by Plato in the Socratic Dialogues. For this, Socrates is customarily regarded as the father and fountainhead for ethics or moral philosophy, and of philosophy in general.

The Socratic method is a negative method of hypotheses elimination, in that better hypotheses are found by steadily identifying and eliminating those which lead to contradictions. The method of Socrates is a search for the underlying hypotheses, assumptions, or axioms, which may unconsciously shape one’s opinion, and to make them the subject of scrutiny, to determine their consistency with other beliefs. The basic form is a series of questions formulated as tests of logic and fact intended to help a person or group discover their beliefs about some topic, exploring the definitions or logoi (singular logos), seeking to characterise the general characteristics shared by various particular instances. To the extent to which this method is designed to bring out definitions implicit in the interlocutors’ beliefs, or to help them further their understanding, it was called the method of maieutics. Aristotle attributed to Socrates the discovery of the method of definition and induction, which he regarded as the essence of the scientific method. Oddly, however, Aristotle also claimed that this method is not suitable for ethics.

A skillful teacher can actually teach students to think for themselves using this method. This is the only classic method of teaching that is known to create genuinely autonomous thinkers. There are some crucial principles to this form of teaching:

Since a discussion is not a dialogue, it is not a proper medium for the Socratic method. However, it is helpful — if second best — if the teacher is able to lead a group of students in a discussion. This is not always possible in situations that require the teacher to evaluate students, but it is preferable pedagogically, because it encourages the students to reason rather than appeal to authority.

More loosely, one can label any process of thorough-going questioning in a dialogue as an instance of the Socratic method.

Socrates applied his method to the examination of the key moral concepts at the time, the virtues of piety, wisdom, temperance, courage, and justice. Such an examination challenged the implicit moral beliefs of the interlocutors, bringing out inadequacies and inconsistencies in their beliefs, and usually resulting in puzzlement known as aporia. In view of such inadequacies, Socrates himself professed his ignorance, but others still claimed to have knowledge. Socrates believed that his awareness of his ignorance made him wiser than those who, though ignorant, still claimed knowledge. Although this belief seems paradoxical at first glance, it in fact allowed Socrates to discover his own errors where others might assume they were correct. This claim was known by the anecdote of the Delphic oracular pronouncement that Socrates was the wisest of all men.

Socrates used this claim of wisdom as the basis of his moral exhortation. Accordingly, he claimed that the chief goodness consists in the caring of the soul concerned with moral truth and moral understanding, that “wealth does not bring goodness, but goodness brings wealth and every other blessing, both to the individual and to the state”, and that “life without examination [dialogue] is not worth living”. Socrates also argued that to be wronged is better than to do wrong.

His life

Socrates left no writings; references to military duty may be found in Thucydides’ History of the Peloponnesian War. He was prominently lampooned in Aristophanes’s comedic play The Clouds produced when Socrates was in his mid-forties. Socrates appeared in other plays by Aristophanes such as The Birds because of his being a philodorian, and also in plays by Callias, Eupolis and Telecleides, in all of which Socrates and the Sophists were criticised for “the moral dangers inherent in contemporary thought and literature”. The main source of the historical Socrates, however, is the writings of his two disciples, Xenophon, and Plato. Another important source is various references to him in Aristotle’s writings.

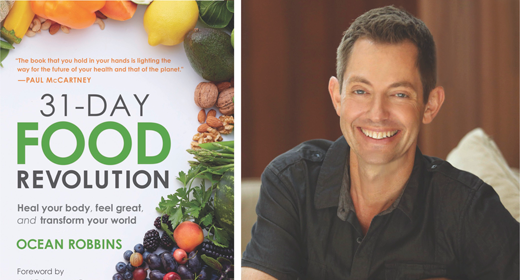

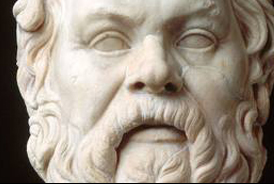

Sculptures and busts of Socrates depict him as a rather ugly man. These portraits were largely based on descriptions given by his disciple Plato, rather than on direct examination of the philosopher by the sculptor or sculptors.

Socrates’ father was Sophroniscus, a sculptor, and his mother Phaenarete, a midwife. He was married to Xanthippe, who bore him three sons. By the cultural standards of the time, she was considered a shrew. Socrates himself attested that he, having learned to live with Xanthippe, would be able to cope with any other human being, just as a horse trainer accustomed to wilder horses might be more competent than one not. Socrates enjoyed going to Symposia, drink-talking sessions. He was a legendary drinker, remaining sober even after everyone else in the party had become senselessly drunk. He also saw military action, fighting at the Battle of Potidaea, the Battle of Delium and the Battle of Amphipolis. We know from Plato’s Symposium that Socrates was decorated for bravery. In one instance he stayed with the wounded Alcibiades, and probably saved his life. During such campaigns, he also showed his extraordinary hardiness, walking without shoes and a coat in winter.

Socrates lived during the time of the transition from the height of the Athenian Empire to its decline after its defeat by Sparta and its allies in the Peloponnesian War. At a time when Athens was seeking to recover from humiliating defeat, the Athenian public court was induced by three leading public figures to try Socrates for impiety and for corrupting the youth of Athens. He was found guilty as charged, and sentenced to drink hemlock.

There is a theory held by some historians that Socrates was a fictional character, invented by Plato and plagiarised by Xenophon and Aristophanes, who was used to articulate points of view which were considered too revolutionary for the author to admit to holding them himself. However, this remains a minority view.

Philosophical Beliefs

Socrates believed that his wisdom sprung from an awareness of his own ignorance. “He knew that he knew nothing” (Thomas 83). Along these lines, Socrates also taught that all wrong doing by man could be attributed to a lack of knowledge (“Socrates” 3). In simpler terms, if a person made an error, Socrates would have believed the error must have been due to ignorance of some sort. Most of his brilliant insights such as these came from the counterexamples he asserted while in debate with another Athenian. Sometimes, Socrates’ questioning of others would lead him to the unexpected acquisition of knowledge. Although he never focused on one specific issue, most of Socrates’ debates were centered around the characteristics of the ideal man as well as what form the ideal government would take. (Solomon 44).

Socrates believed that the best way for people to live was to focus not on accumulating possessions, but to focus on self-development (Gross 2). He always invited others to try and concentrate more on friendships and a sense of true community, for Socrates felt that this was the best way for people to grow together as a populace. The idea that humans possessed certain virtues formed a common thread in Socrates’ teachings. These virtues represented the most important qualities for a person to have, foremost of which were the philosophical or intellectual virtues. Socrates stressed that “virtue was the most valuable of all possessions, truth lies beneath the shadows of existence, and that it is the job of the philosopher to show the rest how little they really know.” (Solomon 44)

Socrates believed that “ideals belong in a world that only the wise man can understand” making the philosopher the only type of person suitable to govern others. Socrates was in no way subtle about his particular beliefs on government. He openly objected to the democracy that was running Athens later in his life. Athenian democracy was not exclusive; Socrates objected to any form of government that did not conform to his ideal of a perfect republic led by philosophers (Solomon 49), and Athenian government was far from that. During the later stages of Socrates’ life, Athens was in continual flux due to political upheaval. Democracy was at first overthrown by a faction known as the Thirty Tyrants, led by a man named Critias, who had been a student of Socrates at one time. The Tyrants ruled for a short time before the Athenian democracy was reinstated, at which point it acted to silence the voice of Socrates.

The trial of Socrates gave rise to a great deal of debate, giving rise to a whole genre of literature, known as the Socratic logoi. Socrates’ elenctic examination was resented by influential figures of his day, whose reputations for wisdom and virtue were debunked by his questions. The annoying nature of elenchos earned Socrates the moniker “gadfly of Athens.” Socrates’ elenctic method was often imitated by the young men of Athens, which greatly upset the established moral values and order. Indeed, even though Socrates himself fought for Athens and argued for obedience to law, at the same time he criticised democracy, especially, the Athenian practice of election by lot, ridiculing that in no other craft, the craftsman would be elected in such a fashion. Such a criticism gave rise to suspicion by the democrats, especially when his close associates were found to be enemies of democracy. Alcibiades betrayed Athens in favour of Sparta, and Critias, his sometime disciple, was a leader of the 30 tyrants, (the pro-Spartan oligarchy that ruled Athens for a few years after the defeat), though there is also a record of their falling out.

In addition, Socrates held unusual views on religion. He made several references to his personal spirit, or daimonion, although he explicitly claimed that it never urged him on, but only warned him against various prospective events. Many of his contemporaries were suspicious of Socrates’ daimonion as a rejection of the state religion. It is generally understood that Socrates’ daimonion is akin to intuition. Moreover, Socrates claimed that the concept of goodness, instead of being determined by what the gods wanted, actually precedes it.

According to Plato’s “Apology,” Socrates’ three accusers, Meletus, Anytus, and Lycon, all leading members of Athenian political society, indicted him on the basis that he ‘corrupted the youth’ of Athens and denied the power of the state gods. The offenses charged did not necessarily carry the death penalty, and Socrates himself suggested to his jury that he should be fined thirty minae (the equivalent of approximately eight years of wages for an Athenian artisan). The “Apology” also suggests that the vote on Socrates’ guilt was very close, and that his jokes about his punishment resulted in more jurymen voting for his execution than had voted to convict him.

Apparently in accordance with his philosophy of obedience to law, he carried out his own execution, by drinking the hemlock poison provided to him.

Socrates has been revered since his execution as a beacon of free speech.

The Socratic Dialogues

The Socratic Dialogues are a series of dialogues written by Plato in the form of discussions between Socrates and other figures of the time. The ideas that Plato communicates are not placed in the mouth of any specific character, but emerge via the Socratic method, under the guidance of Socrates.

In Plato’s philosophical system (Socrates himself left no writings, so the actual content of his teaching is debated), learning is a process of remembering. The soul, before its incarnation in the body, was in the realm of the ideas (or Heaven). There it saw things the way they should really be, rather than the pale shadows or copies we experience on earth. By a process of questioning, the soul can be brought to remember the ideas in their pure form, thus bringing wisdom.

Most of the dialogues present Socrates applying this method to some extent, but nowhere as completely as in the Euthyphro. In this dialogue, Socrates and Euthyphro go through several phases of refining the answer to Socrates’ question, “What is piety?”

The following quotations are from the character of Socrates in Plato’s writing. In this context, it should be noted that the early works of Plato are generally considered to be close to the spirit of Socrates, whereas the later works — including Phaedo — are not.

— Phaedo, 91