by (Sutta Central): SuttaCentral contains early Buddhist texts, known as the Tipiṭaka or “Three Baskets”…

This is a large collection of teachings attributed to the Buddha or his earliest disciples, who were teaching in India around 2500 years ago. They are regarded as sacred canon in all schools of Buddhism.

There are several Buddhist traditions, and each has passed down a set of scriptures from ancient times. SuttaCentral is specially focused on the scriptures of the earliest period of Buddhism, and hosts texts in over thirty languages. We believe this is the largest collection of early Buddhist texts ever made.

SuttaCentral hosts the texts in orginal languages, translations in modern languages, and extensive sets of parallels that show the relationship between them all.

Themes

What are these texts about? The Buddha’s overriding concern was with freedom from suffering. The teachings cover a wide range of topics, including ethics, meditation, family life, renunciation, the nature of wisdom and true understanding, and the path to peace.

The teachings show how to live well so as to be free of suffering. They teach non-violence and compassion, and emphasize the value of the spiritual over the material. Many discourses discuss meditation, while others are concerned with ethics, or with a rational and clear understanding of the world as perceived. They show the Buddha engaging with people from all walks of life and discussing a diverse range of topics. But he said that all of his words have one taste, the taste of freedom.

While there are plenty of summaries and interpretations of his teaching, there’s nothing quite like encountering it in his own words. The early texts depict the Buddha in a vivid and diverse range of contexts, speaking with monastics, ascetics, criminals, kings, businessmen, lepers, prostitutes, paupers, wives, skeptics, friends, and enemies. It’s not just what he says, but the way he deals with this spectrum of humanity, always with kindness, clarity, dignity, and respect.

Content

Fragment of Gandhari manuscript on birch bark, acquired by University of Washington. Afghanistan, circa 1st or 2nd century CE.” />Buddhist texts are traditionally classified as the “Three Baskets”, spelled tipiṭaka in Pali or tripiṭaka in Sanskrit. These are:

- Discourses: Sutta in Pali, sūtra in Sanskrit. These are the primary texts, consisting of records of teachings or conversations by the Buddha or his disciples, and arranged by litarary style or subject matter.

- Monastic Law: Vinaya in both Pali and Sanskrit. These contain the famous list of rules for monks and nuns (pātimokkha). But they are much more than that, including many details of community life, and a multitude of stories about life in ancient India.

- Abhidhamma: Spelled abhidharma in Sanskrit. Abhidhamma texts are systematic summaries and analyses of the teachings drawn from the earlier discourses.

Each Buddhist tradition has passed down separate collections for well over a thousand years. Yet when we look at the Discourses and the Monastic Law, in all major features, and many minor details, they are similar or identical. Since the 19th century, a series of scholars have noted these correspondences and compiled them.

Most of the early texts have been digitized. For the history of this process, see the article Digital Input of Buddhist Texts by Lewis Lancaster in the Encyclopedia of Buddhism. In addition, translations have been produced in multiple languages, mostly focusing on the better-known texts of the Pali discourses.

SuttaCentral draws on this long history to present three main kinds of content.

- Original texts: SuttaCentral presents the original texts in the original languages, including:

- The Pali canon (or Tipiṭaka) of the Theravāda school. Our text is the Mahāsaṅgīti edition of the Sixth Council recension.

- The early Āgama and Vinaya texts from the Taishō edition of the Chinese canon. For our digital source we rely on CBETA.

- A much smaller range of early texts from the Tibetan Kangyur.

- Such fragments and chance findings as are available in Sanskrit, Gandhārī, and other Indic languages.

- Translations: We have gathered translations of early texts in over thirty modern languages. Notable English translations include classic works by Bhikkhu Bodhi, new English translations of Chinese Saṁyukta Āgama texts by Bhikkhu Anālayo, and fresh translations from the Tibetan Upāyikā by Bhikkhuni Dhammadinnā. In addition, we are developing our own sets of new translations, in the belief that complete, accurate, and easy to read modern translations should be freely available for everyone. We have published an entirely new translation of the four Pali nikāyas by Bhikkhu Sujato, which is the first complete and consistent English translation of these core texts. And Bhikkhu Brahmāli is producing a much-needed modern and accurate translation of the Pali Vinaya.

- Parallels: The foundation of SuttaCentral is our sets of parallels. These detail tens of thousands of cases where texts in different collections or languages correspond with each other. The existence of these parallels shows the connections between of the scriptures underlying all Buddhist traditions, a connection that harks back to the Buddha himself.

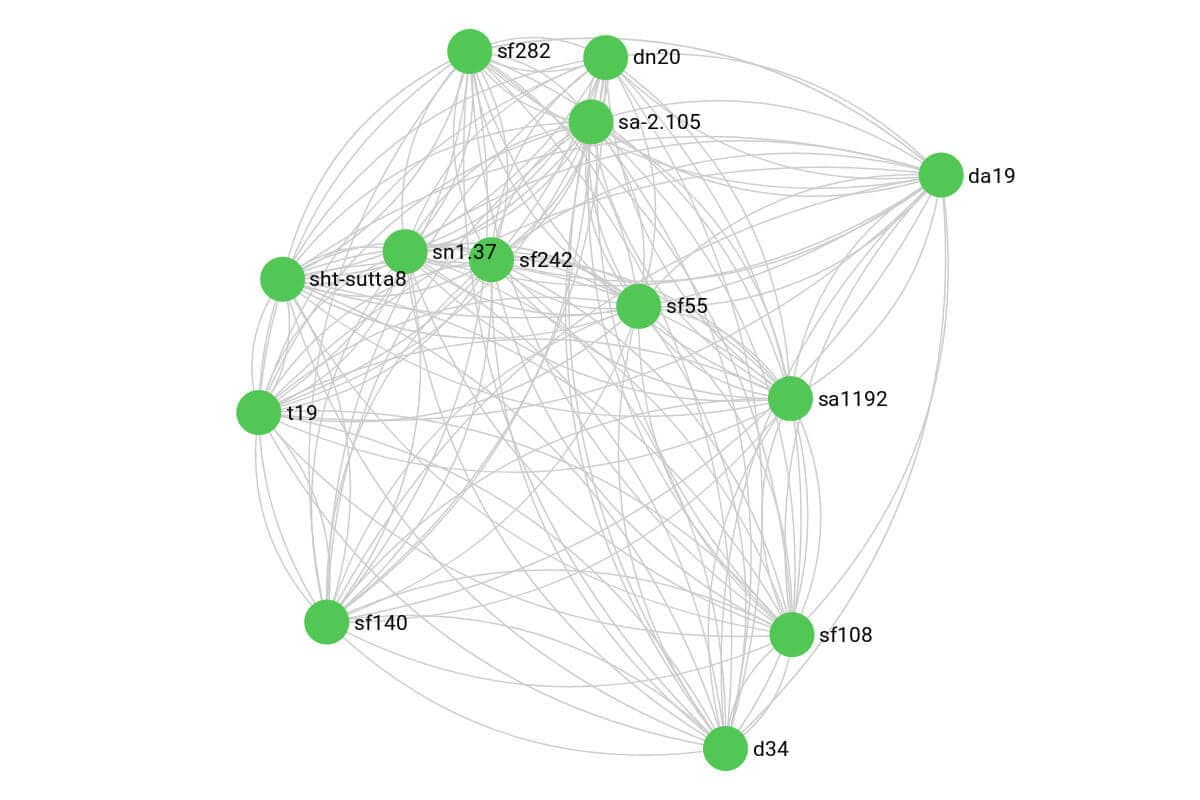

Relations

Visual representation of relationships for Suttas aren’t independent entities. They form a vast interconnected web of teachings. Often the key to understanding one passage lies in a different text. In this way, the Buddhist canons are a little like the internet, with individual pages connected by a web of hidden links.

Most suttas appear in very similar form in more than one collection. We use “parallel” for variant texts that appear to be descended from a common ancestor. Often the texts are so close that this identification is simple. Sometimes, however, there is a less close relationship between two given texts. In such cases we indicate a “resembling parallel”. This doesn’t imply any particular kind of relationship between the resembling parallel and the basic text. It simply suggests that if you are studying the basic text, you might want to look at the resembling parallel, too. For a detailed discussion, see our page on Methodology.

It is no trivial matter to discern what texts should be regarded as parallel. Texts often agree in many details, and disagree in others. When does a text stop being a full parallel and start being a resembling parallel? And when does it become merely a text that bears certain similar features? There are no black and white answers to such questions. Rather, making these identifications draws on the accumulated learning and experience of a succession of scholars. Inevitably there will be disagreements in detail; yet in the main, there is a broad consensus as to what constitutes a parallel. Ultimately, the important point is that these identifications help the student to study and learn from related texts in diverse collections.

Finding Your Way Around

The Buddhist canons have been organized and maintained as highly structured bodies of literature, and this complex hierarchy can be intimidating. We’ve tried to present our material in a way that will be convenient for both experts and beginners. Let’s review how Buddhist texts are organized. Then we’ll see how this is implemented in SuttaCentral.

How the Tipiṭaka is organized

We have already mentioned the overarching concept of the Tipiṭaka. Now let’s look at the sublevels of the structure. For simplicity, we’ll focus mainly on the Pali canon.

Nikāyas

The Pali Discourses are grouped in five main nikāyas or “divisions”. These are not organized by content, but by literary form. The first two—Long and Middle—are organized by length, the Saṁyutta or “Linked” division is organized by topic, and the Aṅguttara or “Numbered” division is organized by numerical sets. These four collections are synoptic; they constitute one largely unified body of text and doctrine, organized mainly for the convenience of the reciters who memorized it.

The fifth nikāya is a rather different kind of collection. The core of it is a set of early texts that are mostly verse. To this was added a series of later texts of very different kinds, showing that this section was considered more open and flexible.

Intermediate levels

The Pali texts have a rather bewildering range of terms for intermediate levels of text structure, corresponding to what we might call a “part” or a “chapter”. Sometimes these sections are crucial for making sense of a text. For example, the saṁyutta is used in the Saṁyutta Nikāya for groups of discourses on the same topic, and the nipāta is used in the Aṅguttara Nikāya for groups of discourses with the same number of items. In the Vinaya, the khandhaka is likewise an essential structural feature. Elsewhere, however, we find structures of less importance, such as the pannāsa or group of fifty discourses. Originally these may have helped organize the texts into manuscripts, but these days they are retained for historical purposes.

Vagga

The smallest level of organization is the vagga, usually translated “chapter” but in fact a set of (usually) ten discourses or other texts. Vaggas may gather texts sorted by a meaningful theme. For example, the “Chapter on Kings” of the Middle Discourses contains ten discussions involving kings. In many cases, however, the vagga is merely a structural convention, and is simply named after its first discourse.

Sidebar

The main navigation is through the sidebar, which is available on every page. This lists all the collections with their various subdivisions. You can go directly to a full collection such as a nikāya, or else drill down to the precise group that you want.

Discourses

For the four main nikāyas, we’ve grouped the Chinese Āgamas together with their Pali parallels. Note that in the Chinese canon, as well as a main full Āgama, there’s usually some extra material; either individually translated suttas, or partial collections.

In the “Minor” section, as well as the eponymous Khuddaka Nikāya in Pali, we include similar material in Chinese and Sanskrit. These are mostly Dhammapada-style texts.

Under “Other” we include the relatively small quantity of material in Tibetan, Sanskrit, and other ancient Indic languages. In many cases, it might be possible to classify this material under one of the five nikāyas. However, the identification is complex and uncertain, so we simply leave it here.

Monastic Code

Unlike the Discourses, for the Vinaya texts we almost always have a clear sectarian affiliation. We therefore use this as the primary means of classification.

All the Vinayas have a similar structure.

- Bhikkhu and Bhikkhunī Vibhaṅga: rules for monks and nuns, together with explanations and commentary.

- Khandhakas: This section, named and organized somewhat differently in the various versions, deals with monastic procedures and lifestyle.

- Supplements: Most Vinayas include some kind of supplement or summary, such as the Parivāra in Pali.

The organization and names of these sections vary, and we follow the sequence found in each text.

Abhidhamma

The relatively few Abhidhamma texts are organized by school and language. Note that abhidhamma is a generic term, and is applied to many later treatises as well. Here we only include canonical texts.

Sutta card list

When you click a link in the sidebar, it opens a list of the corresponding texts, organized as a list of “cards”. Each card contains a complex of information about the relevant text, including references, description, and links to texts and translations. Click on the expander to see the parallels.

A list may be any level of the hierarchy, such as a nikāya, a vagga, etc. You can navigate these at your convenience.

Text pages

You can read the original texts or translations. For original texts, a variety of helpful tools such as dictionary lookup, text-critical highlighting, and so on, is available.

We are moving to a new system based on segmented texts. Not all our texts work this way, but where they do, you can view the text and translation side by side.