by Dr. Alberto Villoldo: In the early 1970s I traveled to Peru with all the earnestness, self-absorption and immodesty of a young maverick…

I had been exposed to Afro-Cuban spirituality, with its drum and candle ceremonies, as a privileged child growing up in the city of Havana before the revolution. Inspired and encouraged by a pioneer in dream research, Dr. Stanley Krippner, I had sought (in the course of a master’s degree in psychology) to expose myself to many of the more phenomenal healing practices of Latin America: urban healing in Mexico, and Candomblé in Brazil. I had graduated in 1972. Then, with Dr. Krippner’s guidance, I designed a nontraditional doctoral program in contemporary psychology in order to study the practices of ancient psychology. I had gone to Peru in search of the fabled ayahuasca, the “vine of the dead,” the jungle liana that was said to take one through an experience of death and back again. I wanted to find an ayahuascero—a jungle shaman, a purveyor of this legendary potion. So I had flown to Cuzco en route to the Amazon jungle, and there met a man who gave me directions.

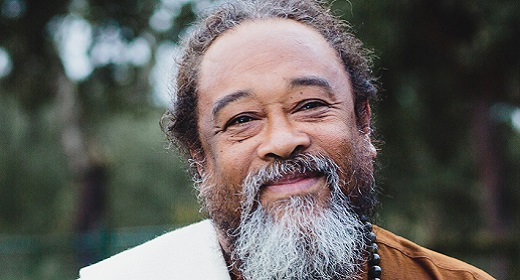

This was Professor Antonio Morales as I remember him then: a small man in a worn and baggy I940s pin-stripe suit, straight gray hair brushed back from a high forehead the color of mahogany. His whole face, its high cheek bones and long Inca nose, might have been carved from that hardwood. His eyes, walnut irises and ebony pupils, reminded me of Rasputin. He was a Quechua Indian, the only Indian on the university faculty. He had introduced to me the fundamental concept of the shaman, the “one who has already died,” the “caretaker of the Earth.” He outlined for me the fourfold path of knowledge, the Medicine Wheel, the journey of the Four Winds. He cautioned me to recognize the difference between having an experience and serving an experience, a distinction that I would not fully appreciate until much later. And he directed me to don Ramón Silva, an alleged ayahuascero who lived in the Amazon jungle south of Pucallpa.

Counting myself lucky to have found a man who had, in his words, grown up with the myths and nursed on the legends of his culture, I headed recklessly for Pucallpa and then some 60-odd kilometers into the jungle. I found Ramón. I tasted the ayahuasca. In a thatched-roof hut on the banks of a small lagoon, a backwater of the Amazon, the tips of Ramón’s fingers strummed a one-stringed harp, his lips sang the songs of the jungle, and fear was redefined for me forever. In what was then the most harrowing full-sensory experience of my life, my consciousness, my very awareness of myself and my environment was altered irrevocably. Even after I succeeded in discounting the trauma of my experience as a substance-induced hallucinogenic episode, I knew that things would never be the same again.

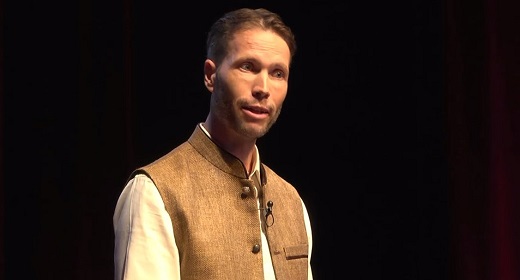

I returned to Cuzco, and old Professor Morales listened matter-of-factly, accepted my tale effortlessly, and defined my experience elegantly. It was the “work of the West,” he explained; I had been rash to seek an experience of this sort without the proper preparation, without the skills to serve the experience, much less understand it. The journey of the Four Winds, as he elaborated on it then, was a metaphorical journey through the four cardinal directions of the Medicine Wheel. It begins in the South, where one goes to confront and shed the past just as the serpent sheds its skin, to learn to walk with beauty on the Earth. The serpent is the archetypal symbol of this direction. The West is the path of the jaguar, where one encounters fear and death; here one acquires posture, assumes the stance of the spiritual warrior who has no enemies in this life or the next. The path then leads to the North, the place of the ancestors, where one has the direct and immediate experience of knowledge, and meets power face-to-face. Finally, there is the East, the most difficult journey that a person of knowledge undertakes. This is the eagle path—the flight to the Sun, and the journey back to one’s home to exercise vision and skills in the context of one’s life and work.

Here was the most elegant description of the “hero’s journey” I had ever heard: a distillate of all those tales of other’s experiences—the very tales that we have fashioned into the myths and religions of our species. Unencumbered by miracles, anthropomorphic gods, and the embroidery of centuries of telling, interpreting, and retelling, the Medicine Wheel was an itinerary for self-discovery and transformation. There was something irresistibly primal and elemental about it, something authoritative, as if it represented one of the earliest descriptions of the phenomenon of awareness, the mechanism of consciousness.

The professor had explained that the prerequisites for engaging this process were simple: find a hatun laika, a master shaman. He or she would be able to discern my intent and my purpose. If I passed muster—if my intent was impeccable and my purpose pure—he or she would guide me on my journey beyond the edge of ordinary awareness.

There was one such man whom professor Morales had heard of, a shaman, a notorious hatun laika who was said to wander the altiplano, the high chaparral plateau of southern Peru. He was called don Jicaram. His name was derived from the Quechua verb ikarar, “to empower.” If I could occupy myself for the next two weeks until the university would be in recess, the professor would be delighted to accompany me on a walking tour of the region.

I spent those next couple of weeks living and working with an urban healer and his wife on the outskirts of Cuzco; two weeks that culminated with my submission to a ritual designed to open my “inner vision.” On a chilly March night, the “veil” that my hosts perceived was clouding my “vision” was carved away from my forehead with my own hunting knife. I saw things that night, witnessed another form of awareness, experienced a different sort of vision, had in effect another profound experience that I struggled to deny, to discount, to reduce to the curious effect of suggestion and traumatic ritual.

Soon thereafter Professor Antonio Morales and I set out across the Peruvian altiplano in search of the notorious shaman, don Jicaram. We walked for almost a week, and we talked. Antonio and I would walk together for many years, make similar treks in the course of our relationship, and I would come to relish those times then as much as I have exalted them since. We became friends, we became compadres, and with his guidance I embarked upon the endless journey that led me to found the Four Winds Society and Light Body School, where we train energy medicine practitioners in the millenary art of shamanic healing.