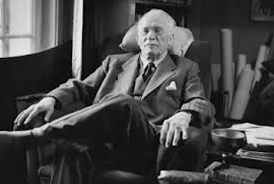

Carl Gustav Jung died 50 years ago today. Alongside Sigmund Freud, he is arguably one of the two people of the 20th century who most shaped the way we think about who we are. But what would he make of the 21st century so far, asks Mark Vernon.

Have you ever discussed whether you were introverted or extroverted? Undergone a personality test on a training course? Wondered what lurks in the shadow side of your character? Carl Jung is the person to thank.

Have you ever discussed whether you were introverted or extroverted? Undergone a personality test on a training course? Wondered what lurks in the shadow side of your character? Carl Jung is the person to thank.

The Swiss psychologist devised a series of personality types. He coined introvert for someone who needs quality time on their own and extrovert (although Jung spelled it “extravert”) for the person who never feels better than when in a crowd. Personality tests, such as Myers-Briggs Type Indicators, draw directly from them.

The shadow side of your character is that part of you which is normally hidden, but sometimes leaps out, catching you unawares. Why is it that the calmest people curse and swear when driving in traffic? Why is it that upright citizens sometimes commit crimes of passion? Jung had an answer – we all carry a shadow.

He also put his culture and times “on the couch” – or rather, in a chair, as he was the first psychotherapist to sit opposite his patients, like a counsellor. He tried to understand the terrible collective energies that drove the two great events of his life, World War I and II.

So what might Jung make of our psychological wellbeing today?

He would see signs of progress. Take the way we worry about the care of children. In the last 50 years, attitudes towards parenting have shifted markedly. Psychologists now widely recognise that children do best when they receive the dedicated attention of their mother or other primary carer from an early age.

This has much to do with the work of British psychotherapists like John Bowlby. But Bowlby’s “attachment theory”, as it is called, was anticipated by Jung. While Freud spoke of incestuous passions in his infamous Oedipus complex, Jung had a very different point of view.

As Anthony Stevens points out in Jung: A Very Short Introduction, it was Jung who first theorised that a child becomes attached to its mother because she is the provider of love and care.

Alternatively, consider the way that our culture tries to tackle ageism and cares about older employees. That again is absolutely right, Jung would say.

“The afternoon of life must have a significance of its own and cannot be merely a pitiful appendage of life’s morning,” he wrote. For a culture with an ageing population like ours, Jung offers a vision of the glories of growing old, seeing it as a path to wisdom rather than a decline into senility.

We shouldn’t despair over our mid-life crises, he thought, but seize them as the chance to find new vision and purpose.

The last 50 years have seen changes in the way mental health is viewed

Modern neuroscience has done much to back up Jung’s understanding of the unconscious too. It confirms that emotional intelligence as well as reason is vital when making decisions.

Further, in much the same way that you mostly aren’t conscious of your heart pumping or your lungs breathing, Jung argued that the unconscious mind is continually working for us. Personality development, he thought, has a lot to do with becoming more attentive to how you are affected by the whole of your inner life, in a process he called individuation.

An integrated personality is what we should seek. It’s the rounded character we love in our wise grandmother or someone famous who has become a reflective national treasure.

But Jung would also be troubled by the way life is unfolding now. For example, he lived in a period “filled with apocalyptic images of universal destruction”, as he observed – thinking of the Cold War and nuclear bomb.

These particular horrors have receded. But it is striking how quickly they have been replaced by new threats. The most obvious is the devastation that is anticipated as a result of climate change. Or you could point to terrorism. And it does not stop there.

We seem to have a fascination with ruination that extends beyond the possible or probable to the purely imagined. Look at how the end of the world provides an irresistible storyline in movies. Or recall how the Rapture predictions of Harold Camping spread like wildfire across the internet last month.

Jung would spot the high levels of mental illness in modern society as well, marked by the boom in prescribed anti-depressants and other drugs in the years after his death. He would see that even politicians and economists are becoming concerned that while a nation’s material wealth can grow inexorably, it does not appear to deliver true happiness or fulfilment.

There are many factors that contribute to these trends. Jung was gripped by those that are psychological and reasoned that such concerns – real or imagined – arise in large part when we become disconnected from our spiritual side.

He argued that while modern science has yielded unsurpassed knowledge about the human species, it has led, paradoxically, to a narrower, machine-like conception of what it means to be a human individual.

This presumably explains why complementary therapies are flourishing in the 21st Century. They try to address the whole person, not just the illness or disease. Or it suggests why ecological lifestyles are appealing, because they try to reconnect us with the intrinsic value of the natural world.

In short, the life of the psyche is crucial. Jung believed it is fed not just by psychology, but better by the great spiritual traditions of our culture, with their subtle stories, sustaining rituals and inspiring dreams. The agnostic West has become detached from these resources.

It is as if people are suffering from “a loss of soul”. Too often, the world does not seem to be for us, but against us.

Towards the end of his life, Jung reflected that many – perhaps most – of the people who came to see him were not, fundamentally, mentally ill. They were, rather, searching for meaning.

It is a hard task. “There is no birth of consciousness without pain,” he wrote. But it is vital. Without it, human beings lose their way.