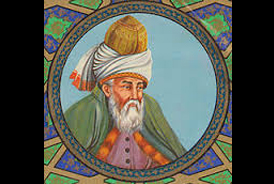

Let yourself be drawn by the stronger pull of that which you truly love. – Rumi, 1207-1273. I love Rumi. Although our earthly paths will never cross, I consider him one of my dearest and most intimate friends.  The guidance and teachings I have humbly received through Rumi’s poems have made the ‘good times’ in my life that much sweeter, and have been a source of solace and comfort in times of challenge. Rumi calls me to remember that I sometimes lose touch with my origin in the Divine Source/God/Spirit/the Beloved, and reminds me that it is this Source through which we are all connected. In his works, Rumi teaches us to honor and respect the many paths available on this human journey even though our path differs from others.

The guidance and teachings I have humbly received through Rumi’s poems have made the ‘good times’ in my life that much sweeter, and have been a source of solace and comfort in times of challenge. Rumi calls me to remember that I sometimes lose touch with my origin in the Divine Source/God/Spirit/the Beloved, and reminds me that it is this Source through which we are all connected. In his works, Rumi teaches us to honor and respect the many paths available on this human journey even though our path differs from others.

To say that Rumi is part of my life is an understatement as his teachings have become infused into most parts of my life. His words appear in my role as a teacher, and in the clinic when I am helping patients. The event space I am the custodian for, The Inner Garden in Toronto, honours his teachings and regularly celebrates his life through music, poetry, and whirling. My marriage was blessed last year by Kabir Helminski, the Sheikh of the Mevlevi Order of Sufism, which was established by Rumi himself almost 800 years ago. Even socially I am drawn to spend time with my Sufi brothers and sisters who hold Rumi so dear in their hearts.

All of this love has now culminated in the planning of a large gathering to honour and celebrate Rumi this November in Toronto. This event is called “Remembering Rumi with Coleman Barks and Friends,” and will be an evening of sacred poetry, music, and whirling.

Your task is not to seek for love, but merely to seek and find all the barriers within yourself that you have built against it. – Rumi

How does someone who grew up in rural Ontario feel so connected and consumed by a Persian poet from the 13th century?

Growing up I enjoyed exploring the woods, playing sports, riding my bike, and hanging out with my friends. This freedom was the freedom of being in the moment. In my early life I was never exposed to poetry beyond “In Flanders Fields,” let alone a 13th-century poet who wrote in another language.

To be honest, I was not an avid reader growing up and over the years this has not changed much. Yet when I read Rumi’s poems, there is something beyond words that pulls me in and opens my heart. I never sought Rumi but his work always seemed to find me. This pull was silent, so much so, that for years I did not notice it. I was introduced to his work by numerous spiritual teachers who I respected. I would like to say I took that as a sign to further investigate, but I did not. Rumi appeared more frequently in the form of coincidences and through the people who entered my life who loved Rumi. This mysterious unfolding happened organically and naturally, and I was never compelled to “know” or to figure out intellectually who Rumi was or why he kept appearing in my life.

After being introduced briefly to Rumi by these teachers, I began using his poem, “The Elephant in the Dark” as my opening to any post-graduate lectures I would give as a teacher of Traditional Chinese Medicine. I resonated deeply with this poem as it exuded humility to me and reminded me, and those I shared it with, to be grateful and open to another person’s perspective. At this point I was aware of Rumi but still was not sure who this mystical Persian poet was.

(I was so ignorant that I thought when they said he was Persian that meant he was from Paris. I shared this with my dear friend Coleman Barks who gently reminded me, “Rumi truly is Parisian as well. The French love him. He is our planetary poet.”)

Coleman Barks was a university professor of poetry and creative writing when, in 1976, he began working on Rumi’s poems after Robert Bly showed him some scholarly translations of the 13th-century mystic and told him, “These poems need to be released from their cages.” Although Coleman had degrees in American and English Literature, he had never heard of Rumi. Captivated by Rumi’s humour, wisdom, and spiritual depth, and the apparently effortless qualities of a poet as famous in the Islamic world as Shakespeare is in the West, Coleman took up the challenge.

Coleman said, “One afternoon, I was looking at scholarly translations from these poems and rephrasing them – trying to make them valid English poems. The minute I started I felt like I was being freed; I felt the presence of his joy and freedom.”

Since 1984, Coleman’s books of Rumi’s poetry have sold more than half a million copies.

Despite my own ignorance, Rumi continued to show up in my life and led me four years ago to the Canadian Sufi Cultural Centre where a community of Rumi lovers meets regularly. Coincidentally, the sheikh, the head spiritual teacher of this order in Turkey and one of the leading authorities on Rumi, came to Toronto during the fall after I began to go there. Realizing I’d better learn more than a handful of poems, I became inspired to buy my first Rumi (and poetry) book and like many in the West I reached for The Essential Rumi by Coleman Barks.

I still remember the feeling of my heart opening and tears filling my eyes as I was overcome with this feeling of connectedness, comfort, and love as I read the first line of the first chapter of this book, “Whoever brought me here will bring me home.” I had experienced this feeling before during mystical experiences and in the presence of different spiritual teachers so it was somewhat familiar to me, but how could words on a page elicit this same response so readily, especially since they were not even in their original language. To me this experience is beyond words but I also think this experience that repeatedly occurs with Rumi’s presence through his words and teachings illustrates how truly special and powerful his words are. I also feel indebted to Coleman’s life-long commitment to making these words accessible in the English language.

I first met Coleman when he performed at the Rumifest that I helped organize two years ago in Toronto. Like Rumi, I consider Coleman a very dear friend who I love very much. Although our words were few it felt as if we knew each other, and even though I have experienced this resonance before, I still find that it is hard to explain this feeling. I think this experience is best illustrated again by Rumi, when he said, “Lovers don’t finally meet somewhere. They’re in each other all along.”

Coleman often speaks of Rumi and his spiritual teachings with this great love, “Rumi was an enlightened being, and it was an enlightened being, the Sri Lankan Sufi master Bawa Muhaiyaddeen, who told me to do this work. For nine years, I was in Bawa’s presence. He lived as Rumi did, and his spontaneous poetry was taken down by a scribe. There are a lot of similarities between Rumi and Bawa Muhaiyaddeen. Both lived their lives in an ecstatic state. Rumi is like a teacher for me. He helps me to know my own identity as something more and vast. My daily work on his poems is like an apprenticeship to a master. Rumi’s definition of enlightenment is full awareness; the longing for the universe or a creative world; a place, or a life, surrounding the universe of the world. These values are found in Sufi poetry: loyalty and hard work. Be loyal to your daily practice, keep working, and keep knocking on the door. It’s like yoga, sitting, meditation, or whatever. My practice consists mostly of listening to Rumi’s art and tasting his awareness to his art.”

I realize I am not alone and my life is not unique, since many people for centuries have been profoundly touched by Rumi’s words.

I asked Coleman, “What keeps you going after all these years?”

He replied, “I hope it is not some form of ambition, but it may have elements of that. For some reason, I do not get bored with this work. It doesn’t feel like work. It is some form of sublime play, a deep relaxation, and a glimpse into a heart-intelligence that I need more of in myself. Here is a short poem of his that I came across recently:

Tonight we are here with a thousand hidden sufis,

concealed, and absolutely obvious, like the soul.

Musicians, mystic-knowers, everybody, keep looking.

We need to find more of these invisible dancers.”

Coleman remarked on these words saying, “Rumi claims there are luminous beings all around us. He calls them ‘hidden sufis.’ What if that is true? What if we inhabit a spirit dimension as well as this one that is so apparent to the five senses? As I work on Rumi’s poems, I feel the reality of what they describe. I feel like bowing in gratitude. No wonder he spontaneously began doing the turn [Sufi whirling known as sema, a devotional meditative dance]. No wonder that my teacher, Bawa Muhaiyaddeen, would suddenly break into song.”

I look forward to November 3rd when I will once again be reunited with local mystics, truth lovers, spiritual seekers, and hidden sufis who share my love of Rumi for a heart opening evening of sacred poetry, music and whirling. I also look forward to seeing and being in the presence of my dear friends Rumi and Coleman Barks.