The Gurdjieff movement deserves renewed attention by sociologists, historians and philosophers of religion who might find  in the data a new axis for organizing their analysis of the contemporary religious scene in America. Such attention will, to some degree, have to be carried out in the status of participant-observer.

in the data a new axis for organizing their analysis of the contemporary religious scene in America. Such attention will, to some degree, have to be carried out in the status of participant-observer.

Scholarly efforts to date to classify the twentieth-century Gurdjieff phenomena have not met with much success. There is the understandable wish to put Gurdjieff into an ethnic or religious tradition, or, failing this, to classify his ideas according to generally known philosophical orientations. This essay seeks to report on field interviews conducted mainly in the San Francisco area during the period 1977-92 and point the reader to historical and philosophical accounts dealing with the subject, with an emphasis on Gurdjieff’s influence in America.

History

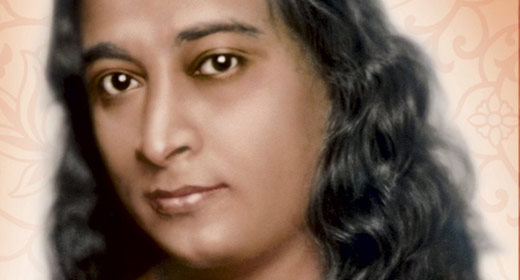

George I. Gurdjieff was born in the area between Greece and the Caspian Sea in the late 1860s or early 1870s. He grew up in a Christian home (Greek or Russian Orthodox), but, as a child, was exposed to a variety of religious practices by local populations. Aside from such generalizations, nothing about his first forty years that can be corroborated independently from his philosophically instructive autobiography, Meetings with Remarkable Men (1963), is available.[3] What is reliably known about Gurdjieff’s life dates from the time of his arrival in Moscow at the beginning of the First World War.[4]

Two accounts provide parallel chronologies of Gurdjieff’s activities during the period 1917-1929. One of these is that of the Russian polymath, P. D. Ouspensky, whose work, In Search of the Miraculous: Fragments of an Unknown Teaching, was first published, posthumously, in 1949. The second is that of Thomas and Olga de Hartmann, whose Our Life with Mr. Gurdjieff, first published in 1964, was reissued in expanded editions in 1983 and 1992.

Gurdjieff was in the Russian cities of Moscow, St. Petersburg, Essentuki, and Tiflis, among others, until 1920, then briefly in Constantinople and Berlin. He arrived in Paris in 1922, where, at first, he rented a house in the Auteuil district that was divided into three flats. Gurdjieff lived on the ground floor, women on the second, men on the third. “Every morning, after breakfast,” Butkowsky recalled, “we all went by tram to Jacques Dalcrose’s studio, which Gurdjieff had rented, to practice our dancing for several hours. . . . Our evenings were spent with Gurdjieff, listening either to him or to two of his pupils discussing various problems, followed by general questions in which everyone would join.”

In October 1922 Gurdjieff and his followers moved to Fountainbleau, located south of Paris. In each of these places he put in motion his experimental center for the study of consciousness. Gurdjieff’s system of ideas and values was so complex and interconnected that, looking back, it is difficult to select a single aspect or idea as the “basic” one. Common to the several approaches Gurdjieff employed was the principle that his ideas needed to be reinvented, rediscovered, in the experience of the pupil. For this reason he said, as Ouspensky later put it, that “the study of psychology begins with the study of oneself.” Self-study, as pupils were to learn quickly, was never a matter of quiet contemplation in a cell; it was just the opposite. Gurdjieff threw his people into unexpected, often strenuous, activities reminiscent of the style of Marpa, the thirteenth-century Tibetan teacher of Milarepa

The most elaborate of these research centers, called the Institute for the Harmonious Development of Man, was that at Fountainbleau, which operated from 1922 to 1934 on the grounds of a mansion that had belonged to a member of the French aristocracy of the eighteenth century. One of the characteristic activities pursued at these institutes was the study of Gurdjieff’s original choreographed dances, which, during the years in Russia, were called “Sacred Gymnastics,” and which, after the arrival of Gurdjieff in France, were called “Movements.”

Financial support for Gurdjieff’s activities in Western Europe came initially from England, where his ideas found a receptive audience, and where, from the early 1920s to his death in 1947, Ouspensky made his principal residence. Later, with Gurdjieff’s tour of New York and Chicago in 1924, a considerable American following developed, thanks in large measure to the successful efforts of A. R. Orage in attracting American writers and artists. Gurdjieff returned to the United States on several occasions during the periods 1929-35, 1939 and 1948-49.

Gurdjieff was in France for over a decade before prospective French pupils expressed interest in his ideas and methods. From 1925 to 1935, while Gurdjieff was absorbed by his writing projects, his ideas and Movements were being introduced to French circles quietly by Alexandre and Jeanne de Salzmann, two pupils who had initially joined Gurdjieff in Russia.

After Ouspensky died in 1947, his widow Sophia, disregarding her deceased husband’s wishes, told followers in England and America to make direct contact with Gurdjieff, who was still alive in Paris. The final period of Gurdjieff’s life, 1948-49, became the harvest years when former and new pupils came to Paris and were introduced to Gurdjieff, who, by all accounts was very ill-and who was just recovering from a recent automobile accident. Some of the new pupils, such as Rina Hands, from John G. Bennett’s group in London, were invited to become part of Gurdjieff’s extended household. A typical day in Gurdjieff’s crowded apartment began at 12:30 or 1:00 p.m. with a one- or two-hour reading from one of Gurdjieff’s then unpublished manuscripts. The reading was followed by a highly ceremonialized mid-afternoon meal. After the meal guests left, only to return about 9:30 or 10 o’clock p.m. for another reading and a late supper and, often, music played on a harmonium by Gurdjieff himself. Typically, guests would leave at 2:30 a.m.

The year following Gurdjieff’s death in Paris in 1949, the first volume of his three-volume work, All and Everything, was published. The first volume was entitled Beelzebub’s Tales to His Grandson: An Impartial Criticism of the Life of Man. The book, written in the format of an epic science fiction novel, treats the Fall of man and the initial arising of civilizations and customs that evoke in the individual impulses and associations becoming to creatures made in the image of God. The book is meant to upset the world view of the reader; in the end, it evokes in the reader feelings of compassion and hope–for himself, if not for humanity at large.

The use to which Gurdjieff societies have made of Beezelbub’s Tales varies. Some of the smaller, independent groups view the book as a canonical text that, like the New Testament in Christian churches, is the object of paraphrase and interpretation. The groups associated with the Gurdjieff Foundations, however, generally eschew discussion of the meaning of the passages of Gurdjieff’s principal book. It is as if they believed that the impact of the book has to be received directly and individually, and that attempts to restate the arguments of the book would, paradoxically, make Gurdjieff’s ideas and message less accessible. It may be, then, that the less said here about the ideas of Beelzebub’s Tales the better; yet, it would be wrong to conclude that every attempt to apply social scientific standards to the interpretation of religious texts–including the one under discussion–is bound to reduce the transcendental to the mundane.

Consider Chapter 27 in Beelzebub’s Tales: here, in the literary vehicle of a grandfather’s instructive reflections to his grandson, Gurdjieff describes how, in a prehistoric period, a great saint brought about a transformation of the religious, social and political outlooks of his people. He accomplished this aim by a reorganization of the psyche of his countrymen, as a result of which the feeling of conscience, normally scarcely noticed in the course of everyday life, came to participate more richly and organically in the social, political and, even, economic transactions of society. As a result of this transformation of outlook, long-standing moral scourges of society such as slavery and social castes briefly disappeared.

In digesting this account the reader is left with multiple impressions: one is that were it ever the case that everyday human relationships were to be governed by feelings other than those typically associated with the presence (or absence) of political and economic power, then such a remarkable change surely would have to be the work of a very great saint indeed. Gurdjieff observes, at the end of this chapter, that contemporary people have only the vaguest notions of a remote “priestly organization” of society, which they mistakenly assume to have been a period of religious tyranny. Perhaps, then, these scraps of information that have been preserved about some ancient civilizations should be given another interpretation. Finally, the reader may experience a half-felt question about how, in his own life, feelings of conscience appear.

Although there are differences in the status accorded to Gurdjieff’s books by Gurdjieff groups, there is less variation in the interest shown in the biography of the founder of their movement. Generally, there seems to be only a minimal curiosity about the details of Gurdjieff’s life–as if to say that, because Gurdjieff taught that life was to be lived in the present moment, only the ideas, music and sacred gymnastics were important. Unlike Christian churches in which every detail of the life of Jesus is made the object of commentary and interpretation, in the Gurdjieff society the historical Gurdjieff is seldom even mentioned. If the tendency in new religious movements toward a cult of the personality could be measured, the Gurdjieff movement would surely score at the very bottom of the scale.

Some Gurdjieff pupils, however, say that reading about how Gurdjieff interacted with society and with individuals of different temperaments is subtly instructive; the instructive quality, they say, is indirect. Although Gurdjieff could not be imitated, still, they say, the harmonic of his fearless and uncompromising attitude still sounds in first-hand accounts of episodes in his life.

Gurdjieff’s Key Pupils

Gurdjieff recruited six or seven key persons who, as followers, made lasting contributions to the preservation of his teaching. These early followers were in large measure responsible for the transmission of his ideas, music, movements and sacred texts.

The Gurdjieff pupil who is best known in the West is P. D. Ouspensky, who expounded “the System” in England and America from the early 1920s until his death in the late 40’s. Ouspensky’s book, In Search of the Miraculous, which narrates the years from 1915 to 1924, was published posthumously with Gurdjieff’s authorization. Ouspensky succeeded in capturing on paper Gurdjieff’s system of interconnected ideas that had been explained, perhaps, for Ouspensky’s ears alone. None of Gurdjieff’s other pupils remotely came close to expressing, in writing, the power of Gurdjieff’s way of working with people through ideas. Ouspensky was key pupil in the spreading of Gurdjieff’s ideas in the United States, where he and his wife took refuge during the Second World War.

A second key pupil was Thomas de Hartmann, a composer who had performed for the Russian aristocracy prior to the First World War. Gurdjieff worked with de Hartmann in the 1920s to compose what was later published as the Gurdjieff/de Hartman music, and which set the framework within which the music for the Gurdjieff Movements are performed.

It is doubtful that the sacred gymnastics of Gurdjieff would have been preserved without Jeanne de Salzmann. A choreographer and dancer, de Salzmann on her own initiative continued teaching the Movements when, in the late ’20s and early ’30s, Gurdjieff had turned to other pursuits. Only later in the 1930s did she succeed in getting Gurdjieff to renew his interest in teaching his singular exercises for developing inner faculties.

Gurdjieff’s writings in three volumes would not have materialized without the administrative and editorial collaboration of Olga de Hartmann, the aristocratic wife of the Russian composer, and a long-time Gurdjieff follower, and Alfred R. Orage, a prominent English editor. Mme. de Hartmann was the person to whom Gurdjieff dictated much of his writings and who worked with Orage and others to render the Russian text into English.

Orage (d. 1934) was a highly regarded English stylist, author, editor and long-time student of philosophy. Orage was in residence at Gurdjieff’s center in Fountainbleau in the early ’20s, prior to being “stationed” in New York for seven years as Gurdjieff’s first “representative” in the United States. Orage, who did not know Russian himself, served as the senior editor in charge of the translation of the Russian text of Beelzebub and Meetings with Remarkable Men into publishable English.

Another Gurdjieff pupil was Sophia Ouspensky, who was associated with Gurdjieff from the Russian period and who had special influence on the development of interest in America in the Gurdjieff teaching. Mme. Ouspensky was a resident of the United States from the Second World War to her death in the early 1960s. She directed the Gurdjieff studies at Mendham, New Jersey.

All of these pupils were Europeans. What, then, of American pupils? In the 1920s and 30s there were numerous persons with public careers who became followers of Gurdjieff’s ideas and who would seek to carry his message to others. In large measure because of Orage’s literary reputation, at first there was a disproportionate representation of writers and editors, such as Jane Heap, Jean Toomer and Gorham Munson. Some American writers in this period, such as as Margaret Anderson, Janet Flanner and Solita Solano (né Sarah Wilkinson), were in contact with Gurdjieff mainly in France.

Jane Heap (1887-1964), born in Kansas, read Ouspensky’s Tertium Organum when the American edition appeared in 1920, met Orage, then Gurdjieff, in 1923-24, and first visited Gurdjieff’s institute near Paris in 1925. During the period 1927-1936 she lived in the Montparnasse district of Paris, where she was the center of a group of women that included Gertrude Stein, Georgette Leblanc, Kathryn Hulme and, when she was in Paris, Margaret Anderson. In 1936, at Gurdjieff’s request, Heap moved to London and there directed Gurdjieff groups until shortly before her death in 1964.

Most contemporary Gurdjieff followers, as would be expected, are not writers, artists or public figures of any sort. At the same time, a sociological slice of the population of Gurdjieffians would not yield a cross-section of American society: the membership in the United States is made up, with few exceptions, of white, middle-class, college-educated people who live in large metropolitan centers.

Post-Gurdjieff developments

By the mid-1950s the Gurdjieff Foundation of New York was formally established, under the guidance of senior American and European pupils of Ouspensky, Gurdjieff and other Gurdjieff followers. The Foundation faced the difficult task of bringing together the followers of Orage, Ouspensky and Gurdjieff himself. Soon, other Gurdjieff centers were set up in cities such as San Francisco, Los Angeles and Washington, D.C.

Jeanne de Salzmann gave structure and direction to Gurdjieff centers worldwide. As one aspect of her activities, she conceived of and initiated work on a feature film, Meetings with Remarkable Men, with director Peter Brook, which was released in 1978 and which was based on Gurdjieff’s autobiography. The film itself is remarkable in giving the viewer an impression of the energy of Gurdjieff’s spiritual quest.

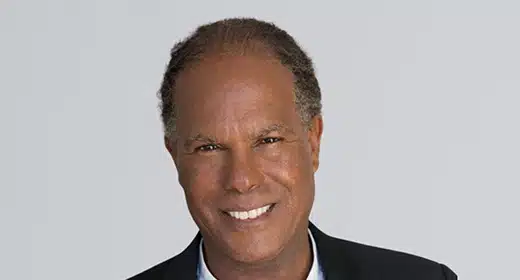

The president of the New York and California Gurdjieff Foundations, meanwhile, was, from its beginning to his death in 1984, Henry Sinclair (Lord Pentland), a Scotsman and Christ College graduate whose father had been Governor of Madras and who had spent some of his childhood in India. Pentland had been an Ouspensky pupil in England prior to the Second World War, and emigrated to America with Ouspensky in 1940. Pentland, who met Gurdjieff only in the last two years of Gurdjieff’s life, was very much the junior of other pupils in New York who had worked with Gurdjieff and Orage from the 1920s.

Gurdjieff, recognizing Pentland’s singular qualities, facilitated his coming to have a position of authority among Gurdjieff pupils in New York. Pentland was closely involved with the publication of Gurdjieff’s and Ouspensky’s posthumous works, although not principally as an editor.

As of mid-1992, several of Gurdjieff’s own pupils remained actively involved in the centers that bear his name; much of the responsibility for the day-to-day activities of these Gurdjieff-oriented centers was in the hands of “second-generation” followers who studied with Gurdjieff’s pupils but who never worked with Gurdjieff himself. In addition, there are a number of organizations that invoke Gurdjieff’s name but have no connection with either the Gurdjieff Foundations or any pupil who worked directly with Gurdjieff.

Methodology

It may seem, in an essay reporting on research on new religious groups and trends, that to use the term “research center” to describe a Gurdjieff-oriented institution is to invite confusion. In the general area of religion and spirituality, social scientists and humanistic scholars do research, the people whom they study are devotees, followers, practitioners or, simply, members. The members, in turn, have beliefs, values, customs and conventions, all of which can be classified and studied comparatively. A “Gurdjieff follower,” then, can be distinguished from a “Zen practitioner” by certain empirically verifiable traits.

Unfortunately, as was said at the beginning, such scholarly exercises, at least those reported in the literature to date, have not yielded much substance. Further, the extent to which academic reporting may capture the nature of the Gurdjieff approach to a religious life is questionable. There seem to be two problems: one, already alluded to, is the tendency of what might be called the taxonomic mind in every scholar, the natural expression of which is the formulation of a new matrix or linear explanation of his topic under study. The second problem might be called that of the false cognate. Numerous interviews with Gurdjieff followers on the nature of the Gurdjieff teaching produces one, nearly uniform, empirical finding, namely, that Gurdjieff followers believe that the ideas in the Gurdjieff oral tradition cannot be communicated accurately outside of the conditions of the activities of the Gurdjieff Foundations. It as if Gurdjieff followers believed that a term like “inner work” as used in the Gurdjieff oral tradition were a false cognate to the term “inner work” as used by the general public. They believe that little is to be gained from discussing with outsiders the ideas and activities of the Gurdjieff Work in the terms that are common in its oral tradition. On the contrary, such discussions could put at risk the specificity of meaning of the Gurdjieff language. They cite the use of the term “enneagram” that Gurdjieff first used (to Western pupils) in the 1916-17 period, and that, subsequently, in the 1970’s and ’80’s was indiscriminately incorporated into new-age psychology and spirituality. Gurdjieffians believe that the further incorporation of terminology from the oral tradition into general public use could have the unwanted effect of creating new and needless confusion about the ideas themselves.

Three conclusions follow. One, some Heisenberg-like Uncertainty Principle may be at work in research on the Gurdjieff phenomena: that is, the reliability of field interview data may vary inversely with the specificity of the content of the data. Two, for reasons already explained, it may not be appropriate to approach the data in the manner of a descriptive linguist bent on capturing the idiom and syntax of the speech acts of communities under study. Three, it may be better to concentrate on Gurdjieff-oriented issues instead of trying to classify the beliefs and practices of Gurdjieff followers.

Gurdjieff issues

The principal Gurdjieff “issue” is the the study of the underlying conditions of one’s life from the point of view of the possibility of inner unity. In his book Beelzebub Gurdjieff observes that although man has the function of conscience that at moments serves the invididual as a kind of North Star in life, this function is only rarely active in the individual’s daily life. How, then, to intensify the rhythm and life of the organism (that is, the individual) so that his half-buried conscience might come to participate in the ordinary exchanges and engagements that his life brings?

As with a number of teachings, a study of “the way” begins with a study of what is not the way. Gurdjieff taught that an individual must make a microscopic examination of moments of awareness of the intersection of thought (or what was taken for thought), feeling and the presence of the body. This examination was not of the sort that required the individual to reconstruct his childhood or any other part of his past, nor was he expected to come to any psychological conclusions as to the reasons for his behavior.

Gurdjieff said that one’s life, at the time of an individual’s initial contact with his work (as he called it), offered the best material for the study of the core issues of the human condition. Unlike other traditions that require that an individual make some real or ceremonial “break” with his past (such as the rite of Baptism in Christianity), in the Gurdjieff world one’s present life is exactly what an individual needs to meet himself in an inner way.

Gurdjieff himself gave a few close pupils a number of spiritual exercises intended to increase their sense of self-presence. One Gurdjieff exercise described by several sources in the 1948-49 period entailed a pupil’s saying to himself the words “I AM.” Gurdjieff instructed the pupil that when he said the word “I” to be aware of his state of feeling, and, in saying the word “am” to be aware of his total state of sensation. Gurdjieff said a pupil should attempt to carry out this exercise at least once an hour. This exericse, as with most of Gurdjieff’s exercises, is either incomprehensible or impossible to re-experience outside of the unique context of the teacher-pupil relationship. For this reason, Gurdjieff pupils generally allude to Gurdjieff’s exercises, but generally insist that only in context of oral tradition can their inner sense be communicated.

Gurdjieff students are encouraged to read Ouspensky’s principal work, but are cautioned that all teachings will have to be re-verified in the individual’s own experience. An example is Gurdjieff’s radical position on human volition. Gurdjieff insisted, at least in the Russian period, that an individual, except in rare moments, cannot “do” at all, has no volition of his own. On the contrary, everything is “done” through him, that is, as a result of the promptings of childhood and cultural conditioning, adult instinctive needs, and the idiosyncratic workings of the personality. Only rarely is anything ever felt or done by the individual in a way that authentically expresses, in one gesture, his body, feelings and mind. The Gurdjieff pupil is asked (although not in so many words), Is this an accurate description of his everyday experience or not? That is, he is asked to verify, and re-verify, the basic ideas of the Gurdjieff teaching with his own experience.

A well-known Korean Zen teacher in the United States, Seung-Sahn, is fond of advising his pupils “Only go straight.” Familiarity with Gurdjieff’s ideas gives a basis for a critique of such injunctions. What does “only go” mean? The part of ourselves that can respond to orders like “[you may] only go straight” is passive and authoritarian. Further, there is nothing in experience that corresponds to “straight.”

Another matter is the importance of undertaking the study of Gurdjieff issues in company and association with others. The group serves as a forum for verifying one’s study of one’s experience with the Gurdjieff ideas and spiritual exercises. Gurdjieff believed that the context of working in a group is beneficial to the individual seeker and to the person responsible for guiding the group’s activities. At Gurdjieff centers in North America (the United States, Canada and Mexico) special attention is given to the study and practice of traditional crafts and disciplines, such as weaving, pottery, carpentry, gardening and translations.

Finally, Gurdjieff Foundations stress the study of what might be called the “presence” of the body. For Gurdjieff followers, the age-old philosophical paradox of the mind-body problem is addressed in a practical way through a many-layered study of the attentiveness, or presence, of the human body. Awareness of the presence of the body is, in the Gurdjieff world, a profoundly rich subject for individual experimentation and discussion. For the human body to serve as a vehicle for the expression of the Will of God (that is, as a communication link between the cosmos and human psychology) it must be sensed and felt in a new way, and its parts or elements must be in the right relation to the others. When Gurdjieff spoke of the “harmonious” development of man, he evidently referred to the possibility of a momentary state of balance between mind, feeling and presence-of-the-body. In Gurdjieffian micro-existential theory, being available at any given moment to receive higher or divine influences requires a progressively more sensitive awareness of nuances of one’s physical existence.

Liturgy

It’s not entirely clear that the sum of what we have called “Gurdjieff issues” points to religion. A brief discussion of liturgical time in Gurdjieff societies might make the religious character of the phenomena clearer.

Perhaps, from a Gurdjieffian point of view, it would make sense to think of religion as the art of invoking liturgical order in human affairs. That is, the claim to religious status by Gurdjieff followers would not be made on the basis of belief in spirits (or any other belief), but on the basis of an oral tradition that addresses the subjects of sacred time, space and order.

We may consider two time dimensions of liturgical order, the year and the day. The Gurdjieff teaching has been adapted to many cultures and societies. In the United States, where, perhaps, there are 5,000 Gurdjieff followers, the Gurdjieffian “year” in the Northern hemisphere follows the cycle of the public schools, from early September to sometime in June. In the summer months, with the exception of special retreats, institutional activities are suspended. During the active months a Gurdjieff-oriented study center will typically offer members the opportunity to participate in a number of weekly activities, such as Movements classes, group meetings, sitting meditation, group craft work, and a lecture-discussion seminar.

With such a program, a member of a Gurdjieff society may be invited to activities four or five nights a week and all day on Saturday or Sunday. In contrast to the liturgical year, which has a period of inactivity, the liturgical day in the Gurdjieff world is every day of the year. The Gurdjieff follower is enjoined to practice a regular discipline of individual meditational sittings in the morning.

Special topics: There are numerous places where the Gurdjieff approach to spiritual direction can be compared to the terminology and orientation of mainline religions and human potential movements. While a systematic comparison will not be undertaken here, it may be useful to give one or two points of similiarity and contrast. The sacred lexicon of the Gurdjieff movement is similar to that of two Middle Eastern religions of nomadic origins (Judaism and Islam) in that there is a strong emphasis on spatial metaphors for religious and spiritual ideas. The use of terms like “path,” “way,” “direction,” “higher,” “lower” and “balance” is common.

A common expression used in Gurdjieff circles from the earliest documented period in Russia is “remembering oneself,” by which he meant the occurrence of moments in which thought, feeling and sensation of one’s physical presence were in an unmistakable relationship. Gurdjieff said that a core problem in modern life is that people do not remember (that is, have experiences of themselves in this reintegrated state). His teaching was intended, in large part, to provide people the needed special conditions in which such reintegrative moments would come to be increasingly possible. these special moments were ones of “I am.”

An outsider might regard an individual’s unique-I as the capability to create a literary whole from one’s lifetime of memories; that is, to be able to connect one’s present circumstances with everything that came before in one’s life. Consider the account of neurosurgeon Oliver Sacks in his story of Jimmy G., the partial amnesiac. Jimmy could not remember his actions from one minute to the next, the ability to tell a roughly accurate, coherent story of one’s life is likely to be an inadequate measure of the meaning of one’s personal life. Jimmy could remember himself in a moment, but the content of one moment would not be remembered in the next moment. (Example: Jimmy has a normal conversation with Sacks, but afterwards, when Sacks leaves the examination room and re-enters ten minutes later, Jimmy insists that, previously, they had never met.) Dr. Sacks concluded, after observing Jimmy at Mass, that Jimmy found some measure of fulfillment and meaning the nature of which was beyond medical science’s ability to describe.

An imperfect analogy exists between the issues that Dr. Sacks described in Jimmy G.’s life and the issues that Gurdjieff followers regard as important in their spiritual quest. Whereas Jimmy did not remember himself from one moment to the next, the ordinary person is likely to remember mainly his tensions, anxieties and goals–the micropolitics of everyday life. To paraphrase Gurdjieff, “An individual begins with ‘I’ in talking about everything he does, but he mainly refers to his habits and fears ingrained in him from childhood, plus his newly acquired resentments and petty conquests; he has all but forgotten the possibility of a sense of ‘I’ that impartially accepts his life as it is.” An individual, in other words, falsely represents to himself his actual ability to stay connected with his deeper self, which, occasionally, is expressed in impressions of impartiality and feelings of compassion in relation to his own life and its circumstances. At this deeper level, then, modern life is much more like Jimmy’s than one would ordinarily believe.

Gurdjieffians believe that no ordered, institutionalized set of words or ceremonies can help the modern person remember himself at this deeper level. There is, therefore, no Book of Common Prayer at Gurdjieff Foundations. At the same time, Gurdjieffians reject the idea that, since everyone is on his own, life offers no help in this morally crucial area. Gurdjieffians, then, seem to be taking a middle ground between ethical nihilism and religious orthodoxy: “It’s not true,” they seem to say, “that there is no basis for ethical or moral philosophy, but that basis cannot be codified in ways that religion and philosophy have tried in modern times. The experience that we are looking for is at the intersection of the personal and impersonal lines of life, of inquiry. The Gurdjieff teaching gives us tools for studying the impersonal.”

Our problem, as Gurdjieff said repeatedly from the beginning of the Russian period, is that we do not have a language in which to express ourselves accurately.

Quite different meanings are given to the term “dream” by Gurdjieff and C. G. Jung, the eclectic Swiss psychologist. Jungian-oriented thinkers use the word “dream” as a technical term that refers to a manifestation or expression of the deeper, unconscious self. The Jungian psychotherapist will encourage a patient to record, and report on, during sessions, interesting dreams that the patient has had during the week. The dream is interpreted, or commented on, in the light of what the therapist understands to be the unresolved issues and natural strivings of the individual at a deeper level of awareness. In contrast, Gurdjieffian-oriented theorists, who also use the word “dream” as a technical term,” stress the idea of awakening from dreams, with the implication that, in general, dreaming is a function of the organism in its most passive state (sleep) and that, therefore, there is no possibility of obtaining in this state the specific benefits from the effort of collected attention. In a Gurdjieff institutional context it would almost never be the case that the occurrence or details of a nighttime dream would be mentioned; on the contrary, since Gurdjieff insisted that day-dreaming was of the same order as dreaming at night, the day (including its dreams) offers all the material needed for the study of oneself.

Conclusion

All religious systems say that man lives from two sources of energy: natural and divine. To use contemporary language, it could be said that man lives from both chemical and alchemical sources of energy. Chemical energy comes from eating, sleeping and impressions of oneself making love and money. Religious systems seem to differ on the fluid dynamics of alchemical energy flows.

The great debate in religion seems to be the nature and activation-mechanism of alchemical energy. Christians warn us, and rightly so, that alchemical energy is wholly other than normal chemical energy. Christians speak of the Grace of God and the Holy Spirit as if to tell us that such energy must never be thought of as something that can be packaged and mass-marketed. The phrase from the prayer attributed to Jesus “and lead us not into temptation,” may refer to the temptation to regard the peak experiences of one’s ordinary chemical life as if they were of alchemical origin. Religion, then, seems to be about the basis of discernment between what Christians call ordinary life, the life of sin, and the life, or footsteps, of Christ.

There are probably two characteristics common to many new religious movements: one is an initial intuitive discernment that the established forms of religion have, in some central way, mixed gold with alloy. It is an intuition that what originally had been an insight into the basis of discernment between what we have called the alchemical and chemical sides of life, but which, over time, had degenerated into mere instruments of personal or institutional power. The second characteristic is probably a willingness to say, in relation to the Christian warning, “But we can make an exception in our individual case.” Such movements would tell us that such-and-such a technique, practice, or set of ideals or articles of spiritual surrender will lead us out of the maze of sensory and mental impulses that make up our lives.

What is interesting about the Gurdjieff teaching is its unusual quietness, approaching silence, about what awaits the spiritual seeker who would ask, What do I have to do?, What is up to me? For what am I responsible?

With the problem expressed in this way, the aims of the Gurdjieff teaching may be expressed in two or three essential points: one, the individual is in profound need of purification in his understanding of the difference between the flows of chemical and alchemical energy in his life; he needs years of impressions of discovering how chemical energy can disguise itself in a beguiling outer form suggestive of the presence of alchemical energy. Second, the individual is responsible for undertaking and maintaining working relationships with others who, also, seek verification of the inner and outer conditions in which contact with alchemical energy becomes more likely. Finally, the probability that an individual will succeed in gaining even a partial discrimination between the two rivers of life, as Gurdjieff called them, will directly vary with the intensity of his association with others similarly embarked on the path of verification.

It’s difficult to know what, then, is the specific gravity of the Gurdjieff phenomena. To listen between the lines, Gurdjieff followers seem to be saying that their approach t offers a new basis for spiritual self-interest, a new reason for living, that did not previously exist in their lives. The Gurdjieff society provides opportunities to associate with others on a new basis of sincerity and inner relaxation not elsewhere found in American society. Gurdjieff followers claim (although not in so many words) to have rediscovered in a practical way the possibility of contact with the sacred mystery of one’s own life and, by extension, that of the lives of others.

Gurdjieff seems to have foreseen much of the present state of confusion in religious inquiry in the West. His teaching invites the religious seeker to develop in himself a moral sensitivity that is nourished, not by techniques or metaphysical answers, but by an ineffable opening to himself and others.